The following essay examines the use of digital media at the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art (BRG) in downtown Vancouver. The first part of the essay provides an inventory of different digital technologies in this gallery space based on personal field notes and observations made during my 2-hour visit on the afternoon of Thursday, February 2nd, 2012 as well as the time spent browsing the BRG’s institutional website. The second part of this essay briefly discusses the use of digital media in the broader context of the physical space of the gallery itself.

In his article critically chronicling his visit to the BRG shortly after its opening, Glass (2009) mentions interactive media three times (p. 15, 19, 20). On two of those occasions he is clearly referring to the “interactive” character of the three digital holographic reproductions in the Audain Great Hall, the BRG’s main room.[i] The third time Glass uses the word interactive to describe digital media, it is unclear if he is referring to those same holographic images or to other technologies as well.[ii]

Aside from the three holographic reproductions in the Audain Great Hall, during my visit, I saw no interactive screen.[iii] Instead, I counted a total of ten non-interactive screens in the three exhibit halls. Eight of these screens were 21.5-inch LED backlit displays manufactured by Apple which could be called electronic media kiosks; one was a large 50-inch Panasonic LED screen[iv]; and the last one was an even larger 60-inch Panasonic LED screen.[v] In lieu of the latter, Glass (2009) mentions three times “a huge, flat, touch-screen monitor…[on which]…viewers can rotate the canoe image 360 degrees and zoom in on it” (p. 18). This interactive touch-screen monitor was not part of the exhibition spaces inside the BRG during my visit. I assume it has been removed since Glass saw it over two years ago.

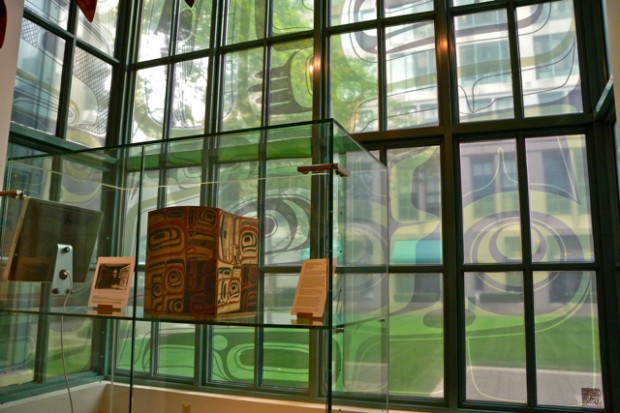

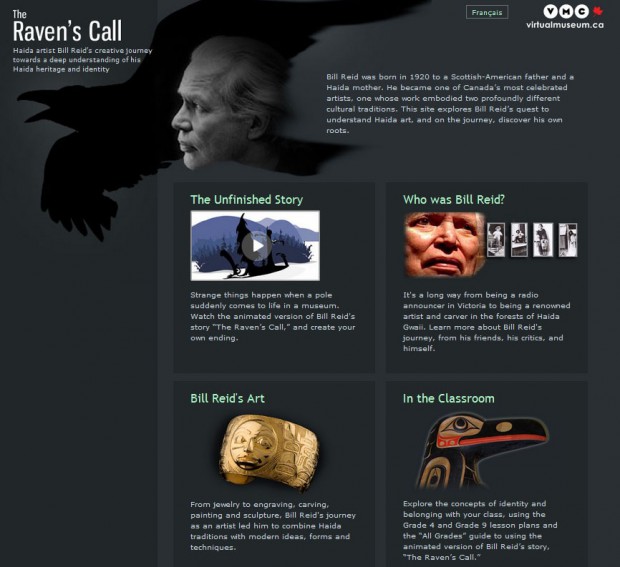

In addition to these ten non-interactive digital displays and three low-level interactive holograms, the BRG’s institutional website offers four related virtual online exhibits, all sponsored by the Virtual Museum of Canada (see Fig. 1).[vi] None of the digital displays inside the BRG offer access to these interactive online resources.

Fig. 1: Screenshot of the interactive website section of the Bill Reid Gallery’s institutional website.

Inside the three exhibit rooms and the mezzanine gallery above the main hall, I observed the digital displays, exhibit spaces and how visitor “interacted” with these from 2:30 pm to 4:30 pm. Other than myself, there were only two visitors during this period: two older women, who spent most of their time in the third hall examining the exhibit curated by Martine Reid, the artist’s widow. For the twenty minutes or so that they were in this space, these visitors only looked at the jewelry in the exhibit cases. They did not even seem to notice the one digital display in that room broadcasting the 17-minute CBC documentary video titled Restoring Enchantment: Gold and Silver Masterworks by Bill Reid. They spent a total of less than five minutes in the other exhibit rooms.

The first point to be made from my observations is that, aside from the low level interactive holograms, digital media is not used interactively inside the BRG. It is used as a tool to broadcast videos and images. The second point to be made is that the interactive features that extend the BRG’s exhibit outside the physical space of the gallery, namely, the four interactive sections of the institution’s website are not accessible to visitors inside the gallery space which seems odd considering how sophisticated they are and how much money visibly went into making them. The third point to be made from my experience of the space is how digital media technology integrates with the design of the space from a curatorial point of view.

Isaac (2008) has argued that the digital interactive kiosks entitled the “Window on Collections” (WOC) of the inaugural exhibit space at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, DC, had a significant impact on how knowledge was being communicated, interpreted and experienced in the context of the exhibit (p. 306). One of the main points being made in her article is that the technological means by which knowledge was being conveyed in this exhibit ideologically reinforced conventional Western epistemological frameworks and institutional tropes. Given that the digital displays at the BRG were similar (but not the same since they were not interactive), it is fair to ask if the BRG’s use of digital media equally problematizes the question of how art is being experienced in this gallery.

Unlike Glass (2009), I did not find that “the inclusion of questionable “high-tech” displays actually do an artistic and intellectual disservice to the complex man who created many of the noteworthy objects on exhibit” (p. 14). In fact, quite to the contrary, I found that the BRG’s use of digital media downplayed the technology. It would be difficult to support my argument by referring to the two visitors that were present at the time of my visit, but it is still noteworthy that neither of them paid any attention at all to the digital displays.

Upon surveying the exhibition spaces of the BRG, what struck me the most was how multimediated they were: the presence of an oscillating tension between immediation and hypermediation, as defined by Bolter and Grusin (1999). While the logic of immediacy in design strives to erase all traces of the medium by leading “one either to erase or to render automatic the act of representation” (p. 33), that of hypermediacy uses design strategies that deliberately exposes the form, which “makes us aware of the medium or media and (in sometimes subtle and sometimes obvious ways) reminds us of our desire for immediacy” (p. 34).

In discussing these concepts, Isaac (2008) opposes them, citing Bolter and Grusin’s idea that hypermediacy dominates in non-places such as museums (p. 300). In my view, this constitutes a misreading of Bolter and Grusin’s (1999) quote which actually refers to Augé’s concept of non-places. Contrarily to what Isaac suggests, the authors do not mention or even allude to museum spaces (pp. 178-179). Admittedly, the BRG is not NMAI and I was not present at the latter’s inaugural exhibit so it is not my place to discuss Isaac’s observations of that space.

But I was physically inside the BRG and from this I can say that I felt that I was in a space that had been successfully multimediated by design, that is, that the design strategies used to curate the space integrated an unusually high number of different media that, in a paradoxical way, drew attention to themselves while blending into each other. Thus, the digital displays were no more to be perceived, as “museum objects” as Isaac (2008) describes (p. 306), as were the exhibit cases, but even more to the point, as were the windows in the first exhibit room decorated with transparencies that reproduce Haida art motifs (see Fig. 2); the small series of b&w photographs of totem poles in the jewelry cases; the large b&w mural-size photographs of Reid making jewelry in this third exhibit room; the large color photographs of Reid’s art that are laid out like wallpaper on wall panels next to the holograms in the Audain Great Hall (see Fig. 3) or the b&w wall panel photographs at the end of this same room.

In other words, I found that there was an interesting variety of image-based media that had been chosen to decorate the space and to augment the visitors’ understanding of Reid’s world. Although one could call into question why some images or videos were chosen rather than others, from a curatorial and design perspective, I thought that the exhibit spaces were unified and had a thematic integrity. This, I believe, should be a curatorial priority.[vii]

Following Isaac’s (2008) claims, it could be tempting to say that the digital media technology in the BRG is symbolic of the complex relationship between Western and Native modes of knowledge production. But that would grossly simplify the argument. In fact, what I found was that some of the art on exhibit and architectural design of the space itself were far more emblematic of the agonistic exchanges between the colonizers and the colonized. The representation of Reid’s sculpture of the “Spirit of Haida Gwaii” on Canadian stamps and twenty-dollar bills on display in the mezzanine gallery and the clay-colored archway in the Audain Great Hall made up of 21 low-relief tiled representations of Christian missionary scenes (see Fig. 4) are far more fraught in this gallery space than is the presence of digital displays, as are the Chilkat silk ties, the frog bottle or the silver-plated raven ladle (see Fig. 5) in the gift shop, whose trade Robinson (2010) reminds us are necessary to the economic survival of public art galleries that have lost their government funding.

In summary, I found that the digital media inside the BRG is used mostly as low-level interactive broadcasting tools that integrate harmoniously with other image-based elements of design.

Endnotes

[i] Here, Glass uses the word “interactivity” to describe how holographic images display different 3D perspectives depending on the vantage point of the viewer. This roughly corresponds to what Zimmerman’s (2004) refers to as functional interactivity, best described in terms of how design can structure the reading of a text (p. 158). On the scale of Zimmerman’s four level of interactivity, functional interactivity is considered a low level interactivity.

[ii] See passage that reads: “the main room presents examples of his work in various media amidst holographic and interactive digital reproductions of some of his iconic sculptures” (p. 15).

[iii] Details about the complete inventory of the digital media in the BRG at the time of my visit are listed in Appendix A of this essay.

[iv] This screen was used to broadcast the documentary titled I Called Her Lootaas (1988) next to which a DVD case of the movie promotes its availability at the gift shop.

[v] This screen was used to broadcast The Journey of Lootas on the Seine River (1989) on the wall facing the holograms.

[vi] The first is The Unfinished Story, a 3-minute video of “The Raven’s Call”, a short open-ended story written by Bill Reid which site visitors are encouraged to interact with by creating their own ending and sharing it with other visitors online. The second is Who Was Bill Reid?, a photo biography and series of video clips that describe “the influences that shaped Bill Reid’s identity” told “in his own words” (The Raven’s Call website, 2010). The third is a section titled Bill Reid’s Art, which presents an online image and text catalogue of Reid’s artwork which the viewer can view in an image-driven database form or in a text-driven essay format divided according to the three stages of Reid’s artistic development : Pre-Haida, Haida, and Beyond Haida. The fourth and last virtual online exhibit is titled In the Classroom. It essentially provides educational institutions and teachers a didactic text-based lesson plan divided into 3 different learning categories (grade 4, grade 9 and all grades).

[vii] On this subject, see my previous post entitled “My Visit at VAG” published on January 15, 2012 in the IAT 888 blog.

Appendix A : inventory of digital media in the BRG on February 2, 2012

8 X 21.5-inch non-interactive LED backlit APPLE display kiosks

#1: CBC Presents, Introduction to the Life and Work of Bill Reid, 7-minute video.

#2: Out of the Silence (1971), 14 minutes; photographs by Adelaide de Menil; text and narration by Bill Reid, courtesy of the Bill Reid Estate.

#3: The Bill Reid Gallery, The Haida Village, 8-minute video.

#4: CBC Presents, Haida Canoes, 10-minute CBC video.

#5: CBC Presents, Restoring Enchantment: Gold and Silver Masterworks Works by Bill Reid, 17-minute video.

#6: The Final Tribute, from the documentary the Raven in the Sun: Bill Reid CBC Life and Times (2000), 6-minute video.

#7: The Spirit of Haida Gwaii, 15-minute video.

#8: Mythic Messengers Bronze, “Sharing tongues, bridging the gap between communities”, 5-minute video.

1 X 50-inch non-interactive Panasonic LED screen

#9: I Called Her Lootaas (1988), 50-minute documentary produced by Nina Wisnicki, narrated by Bill Reid.

1 X 60-inch non-interactive Panasonic LED screen

#10: The Journey of Lootaas on the Seine River (1989), photographs by Carey Linde, montage by the Bill Reid Centre for Northwest Coast art studies at Simon Fraser University.

3 X mural low-level interactive digital holographic reproductions

#11: The Spirit of Haida Gwaii or “Jade Canoe” (1994), medium: cast bronze with jade patina, dim: 605 cm x 389 cm x 348 cm.

#12: The Screen (1967), medium: laminated red cedar, dim: 213 cm x 190.3 cm x 14.6 cm.

#13: Raven and the First Men (1986), medium: onyx, carved by George Rammell under Reid’s supervision, dim: 73.6 cm.

Sources

Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art. (2010, May 8). The Raven’s Call [website]. Project developed by the Bill Reid Foundation and 7th Floor Media, in partnership with the Virtual Museum of Canada (VMC). Retrieved on February 2, 2012 at www.theravenscall.ca, www.virtualmuseum.ca, or www.billreidgallery.ca..

Bolter, J. D. & Grusin, R. (1999). Immediacy, hypermediacy and remediation. In Remediation: understanding new media, (pp. 20-50), Cambridge, Mass. : MIT Press.

Fairweather, P. (2010, May 7). Virtual exhibition celebrates one of Canada’s greatest artists [press release]. Retrieved from http://www.billreidgallery.ca/Exhibition/Media%20Release_The%20Raven%27s%20Call.pdf

Glass, A. (2009, Spring). Review essay: selling the master (piece by piece): enchanting technologies and the politics of appreciation at the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art. Museum anthropology review 3 (1): 14-24. Retrieved on February 3, 2012 on http://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/mar/article/view/102/181.

Isaac, G. (2008). Technology becomes the object: The use of electronic media at the national museum of the American Indian. Journal of material culture 13 (3): 287-310.

Reid, M.J. (2010, Spring). Letter to the editor*: Response to Aaron Glass’ 2009 Review Essay on The Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art. Museum anthropology review 4 (1): 48-53. Retrieved February 3, 2012 on http://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/mar/article/view/431/507

Robinson, M. (2010, Spring). Letter to the editor*: Response to Aaron Glass* 2009 review essay on the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art. Museum anthropology review 4 (1): 55-55. Retrieved February 3, 2012 on http://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/mar/article/view/432/509

Zimmerman, E. (2004). Narrative, interactivity, play and games. . In N. Wardrip-Fruin & P. Harrigan (Eds.), First person: new media as story, performance and game (pp. 154-164). Cambridge, Mass. : MIT Press.

List of Figures

Note: the Bill Reid Gallery prohibits visitors from taking photographs with or without flash.

Figure 1:

Screenshot of the interactive website section of the Bill Reid Gallery’s institutional website.

Source: http://theravenscall.ca/en

Figure 2:

Photograph showing the Haida-motif window transparencies in the first exhibit room.

Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/miss604/4721393778/sizes/m/in/photostream/

Figure 3:

Photograph showing the Audain Great Hall with color panels on the wall to the left.

Source: http://arianecdesign.com/a-visit-to-the-bill-reid-gallery

Figure 4:

Photograph showing a high-angle wide shot of the Audain Great Hall archway.

Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/miss604/4721391966/?q=bill%20reid%20gallery

Figure 5:

Photograph of the silver-plated raven ladle sold at the BRG gift shop (cropped).

Source: http://www.billreidgallery.ca/PlanVisit/GiftShop.php