Not Our Parent’s Dinosaurs? A Response to Science World’s Extreme Dinosaurs

Since July 30, Telus’s Science World has been overrun by “Extreme Dinosaurs”. Science World’s newest gallery space (10,000 ft2) hosts the feature exhibition, while an animatronic dino in a ranger hat greets visitors at the entrance, a corollary IMAX, “Dinosaurs Alive!” shows in the Omniplex Theater, and green dinosaur signage pervades promotional screens and print media, not to mention that the permanent “Search” gallery also boasts a “towering T-Rex”.

I went to Science World on a weekday morning. Most of the visitors were children about ages 5-10 on school trips, who had clearly been let loose in the “Puzzles and Illusions” game areas on the first floor, a whirlwind of buzzing, flashing, and button-pushing activity. My friend and I made our way up to the second floor, and wandered around the “Eureka!” gallery, packed full of all our favorite tornado-making, parachute-launching, and other science magic-making activities we remembered from our own school field trips. At noon, we headed up the ramp to see the IMAX, “Dinosaurs Alive!” (what trip to Science World is complete without an IMAX show?) where we were assured that the show was so “real” that we might become dizzy. The lights dimmed. Showtime!

The film begins with two CGI dinosaurs fighting to the death (Extreme!). As they fall still, the scene fades to reveal the fossil inspiration for the scene: “80 million years ago,” Michael Douglass tells us, “two dinosaurs, a crested Protoceratops and a sharp clawed Velociraptor fought to the death. Somehow as they died in the sands of the Gobi desert, their battle was frozen in time . . . a mysterious glimpse of life and death in the age of dinosaurs.” The screen becomes a desert surface, and wind begins to blow away layers of sand to reveal the words “Dinosaurs Alive”, just as a giant claw rips through the text and the screen goes black. From there, the film introduces dinosaurs as the “creatures” that “roamed the earth” for over 150 million years (Why do dinosaurs always “roam”?), and then begins a narrative using historic footage of early Paleontology expeditions and their legacy—current digs run by the American Museum of Natural History (they sponsored the film, after all). The film continues the metaphor of “revealing the sands of time” throughout the film, and intersperses CGI “lifelike” renderings of the digs’ finds, which likewise “reveal” never-before-understood elements of dinosaur physiology or lifestyle.

Ready to see more dinosaurs, we headed immediately to “Extreme Dinosaurs”.

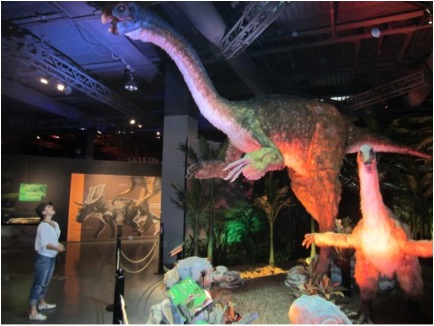

Rounding the corner into the exhibit, we hit a wall of sound–screeching, growling, and squawking. The dim but colorfully lit gallery was full of foliage and life-size animatronic dinosaurs. The introductory Panel read: “These unusual beasts aren’t your parents’ dinosaurs–with ferocious feathers and handsome horns, some of these dinosaurs are unlike any you’ve seen before. We’d go as far as to say they’re extreme!”

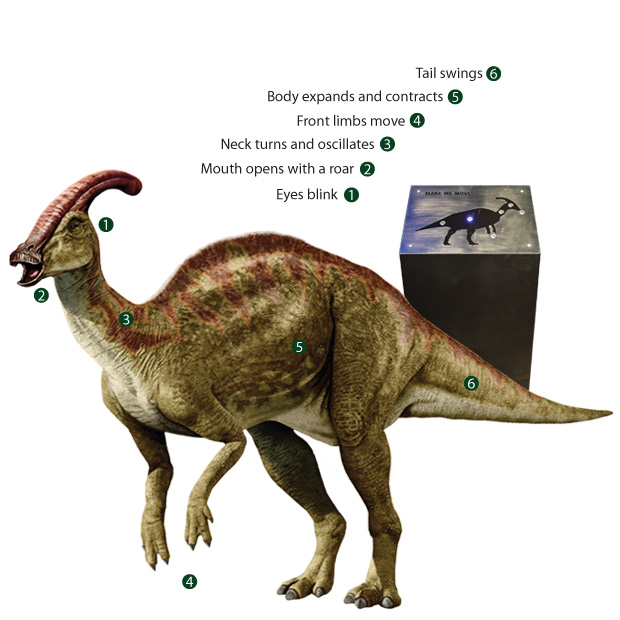

A roped path lead us to a first display, which had frozen and gone silent on our approach. I walked in front of “Alxasaurus”, a long-necked, “feathered”, bipedal dinosaur that began to make squawking noises and open and close its beaklike mouth. As my friend and I walked across the display, all of the dinosaurs chimed in—a cacophony of dinosaur sounds. Some of the dinosaurs were covered in faux fur painted to look like feathers. Others had an allover leathery appearance. All appeared to be made of some kind of rubber, which jiggled a bit as they moved. A few in the gallery allowed us to push a button for each movement, one at a time.

I left the gallery perplexed. It was a new exhibition, but aside from one computer screen terminal exploring dinosaur sound passages, none of this seemed very new—something like Rainforest Café meets Disney’s Tiki Room. It wasn’t until later, perusing Science World’s website and the links I explored from there, that I had a fuller story.

* * * * * * * *

“Extreme Dinosaurs” Science World’s website says, “gathers some of the world’s strangest dinosaurs . . . These life-sized animatronic creatures come to life and let you experience first-hand what it would have been like to share our world with these wacky reptiles.” The gallery features 19 animatronic dinosaurs and two full-scale skeleton replicas. An online interview with the exhibit’s curator, Brian Anderson (linked on the website) boasts that the new gallery features “classic dinosaurs” like tyrannosaurus and triceratops, but also discoveries from 2005 and 2010, “The biggest, weirdest, coolest dinosaurs you’ve ever seen.” (http://www.vancouversun.com/Video+Extreme+Dinosaurs+exhibit+Vancouver/5176124/story.html) The website also has links to two videos showing the dinosaurs’ installation—one of unloading the exhibit, and one of a time-lapsed video of its construction.

Unloading:

Time-lapsed:

I also found a fact sheet about the gallery which provides some insights into its making:

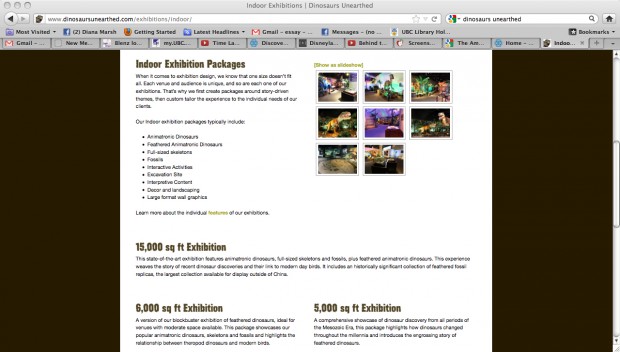

Extreme Dinosaurs Fact Sheet

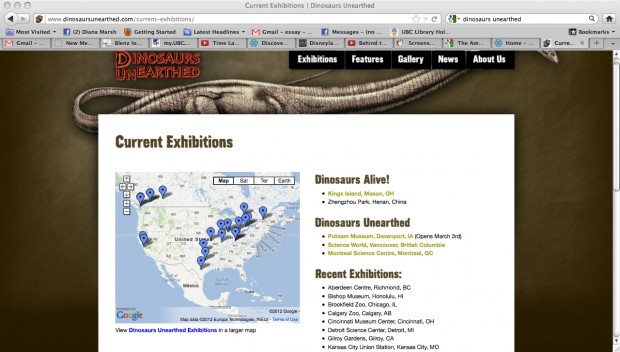

From there, I began to search “Dinosaurs Unearthed”, the Richmond company that created the animatronic dinosaurs for the show. As it turns out, Dinosaurs Unearthed is a huge company, specializing in animatronic dinosaur exhibit “packages”: “Our story-driven exhibitions combine life-sized animatronic dinosaurs, full-scale skeletons, intriguing fossils, interpretive content and interactive activities in a naturalistic indoor setting. Designed and handcrafted by a team of experts, our displays deliver a complete picture of dinosaur discovery.” Like ordering a new Mac computer online, Dinosaurs Unearthed lets institutions choose packages by gallery size, budget, and special features.

“Each venue and audience is unique” the website says, “and so are each one of our exhibitions. That’s why we first create packages around story-driven themes, then custom tailor the experience to the individual needs of our clients.” Clients (museum and tourist institutions) can choose from 3,000 to 15,000 ft2 gallery options, as well as outdoor displays. They can also choose what kinds of interactive elements they want, for instance:

Dinosaurs Unearthed has exhibitions like Extreme Dinosaurs all over North America. The exhibits themselves (along with their animatronic dinos) are their own forms of reproducible technologies (Benjamin 2010).

And, as it turns out, the technology used for Dinosaurs Unearthed is not unlike what was used in the original Tiki Room at Disney World, the first-ever animatronic entertainment display:

Behind the Scenes of the Tiki Room

Disney Imagineering pioneered audioanimatronics in the early 1960s, and in fact trademarked the term in 1964, a year after the Enchanted Tiki Room opened. Back when Disney was pioneering this technology, a clay figure was made to-scale, which became the model for hand-made plaster molds then covered in Duraflex, a weather-proof and flexible vinyl-like material (Adams 1991, 100). Today, a “maguette” is the term used for the to-scale clay model, which is usually laser scanned by a 3-D digitizer to create a computer model, which in turn is used to create the pieces of the dinosaurs in rubberized foam. While Dinosaurs Unearthed’s specific technologies and the process are a bit mysterious, I did find one online interview with Jennifer Chow, Dinosaurs Unearthed’s Business Development Manager, at the IAAPA (International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions) Trade Show (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u43eUp7BLtQ) who mentioned that “They’re all animatronics and they’re all motion sensored and they all move with movement and sound.” Interestingly, though, because my friend and I hadn’t registered that the dinosaurs were motion sensored—we’d just thought they repeated on loop—we were unaware of this new technology.

* * * * * * * *

Extreme Dinosaurs and its complementary IMAX showing and website offers an interesting case in thinking about digital technologies. It’s not clear that visitors know that the animatronic dinosaurs are the result of digital technology, nor that even the very earliest animatronic entertainment was computer-controlled. The lack of information about the animatronic dinosaurs in the gallery make them an “extreme” (!) “technology of enchantment”, in the way that Gwyneira Isaac uses Gell’s terminology to argue that “as the majority of viewers do not understand the digital codes used to convert objects into numbers, the process of the images’ production remains concealed” (Isaac 2008, 291).

Isaac also argues for thinking about digital technologies as new museum objects: “The interplay between . . . digital images and their material referents, has initated new ways of responding to and experiencing museum objects” (Isaac 2008, 297) and “media technology itself becomes a museum object” (Isaac 2008, 306). Interestingly, though, dinosaurs have never really been shown as “original objects”. Rather, even the very first dinosaur exhibits, and certainly the most popular, largely consisted of casts of fossils in the field—the fragility and incompleteness of most fossil specimens has always prevented “real”, whole skeleton displays (Mitchell 1998). Dinosaur displays therefore present an interesting case in blurring the boundaries between original and duplicate and for thinking about what have historically been categorized as “museum objects”. Perhaps these are “our parent’s dinosaurs” after all.

As with Disney’s early Tiki Room, where “fun” resulted “from transport into mysterious fantasy realms . . . and admiration for the wondrous and clever workings of plastic and electronic technologies” (Adams 1991, 99), so too Extreme Dinosaurs privileges fantastical imaginings as its primary form of engagement. And like the Tiki Room (which emphasized the superiority of North American culture in opposition to Pacific Island cultures), the particular combination of digital media used in Extreme Dinosaurs conveys a clear narrative of Western and scientific progress, made possible by the myth of paleontologist-as-hero. As Benedict Anderson reminds us, “museums, and the museumizing imagination, are both profoundly political” (Anderson 1991, 178).

Yet the mix of digital media experiences made possible by Extreme Dinosaurs is also interesting in terms of digital and museum “contact zones” (Srinivas et. al 2010; Clifford 1997). While the main gallery refuses access to the production and formulating knowledge systems which shape its content, the accompanying film, Dinosaurs Alive!, as well as videos and related links accessible via the web allow audiences to consider object “biographies and their associated narratives” (Srinivas et al 2010, 745). In fact, taken together, the supplementary Extreme Dinosaurs content expose both “Stories and narratives about objects” and “uses and practices around objects” (Srinivas et al 2010, 754). At Science World itself, seeing CGI renderings of dinosaurs, paleontological dig sites, and footage of fossils and “museum catacombs” in Dinosaurs Alive! perhaps goes some way toward presenting “unprecedented types of dialogs and information to be uncovered and performed” (Srinivas et. al 2010, 738). Online, videos showing trucks unloading dinosaur parts go some way to allowing each object to “‘speak’ about its place of origin”, even while “it becomes a public spectacle, interpreted by diverse publics, each maintaining their own cultural imaginations” (Srinivasan et al 2010, 737).

Bibliography

Adams, Judith. 1991. The American Amusement Park Industry: A History of Technology and Thrills. Boston: Twayne Publishing.

Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin und Spread of Nationalism, revised edition, London: Verso.

Benjamin, Walter. 2010. “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility” [First Version]. Grey Room 39, pp. 11-37.

Clifford, James. 1997 Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

“Extreme Dinosaurs” Science World, Telus World of Science, 02/05/12: http://www.scienceworld.ca/dinos.

Isaac, Gwyneira. 2008 “Technology Becomes the Object: The Use of Electronic Media at the National Museum of the American Indian”. Journal of Material Culture 13(3):287-310.

Mitchell, W. J. T. 1998 The Last Dinosaur Book: The Life and Times of a Cultural Icon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Srinivasan, Ramesh, et al. 2010 “Diverse Knowledges and Contact Zones within the Digital Museum”. Science, Technology, & Human Values 35(5):735-768.