Context from Display Design: Affording Perspectives

Kristin Carlson

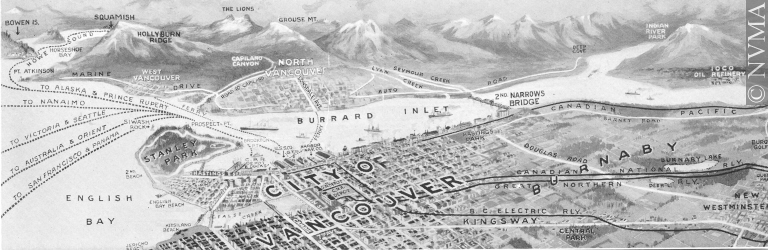

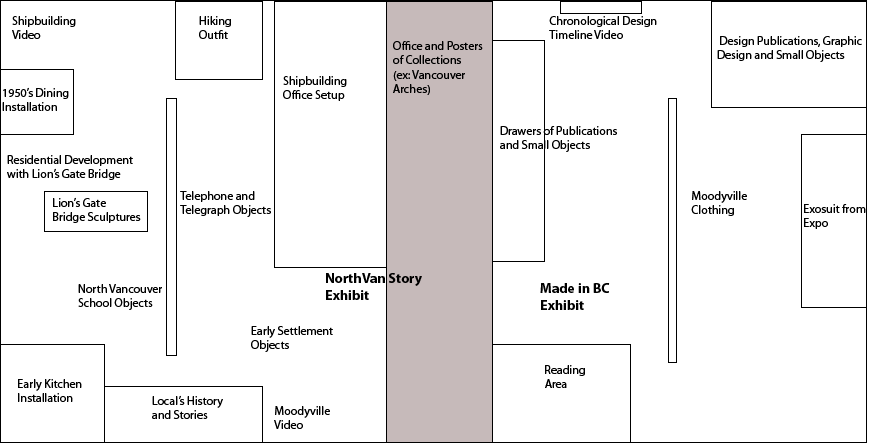

The North Vancouver Museum is a small, 2-room structure focused on the surrounding area’s history and culture. The permanent physical exhibit was titled: The North Vancouver Story and the current temporary physical exhibit was titled: Made in BC: Homegrown Design (See Figure 1). The museum website includes 2 virtual exhibits (on Moodyville and local mountaineers) and 4 collections of video (3 of which are exhibited on screens in the physical museum exhibits). In the physical exhibit, objects are presented in chronologically ordered, themed displays to give context to the North Vancouver story (North Van Museum website). It felt obvious that the exhibit context I experienced was designed to be a linear path, the way physical objects were displayed held a limited and unassailable perspective. While the local mountaineer virtual exhibits presented broader perspectives, the design of the virtual display was a flexible web of information that connected characters, locations and equipment to create a rich context for local adventures.

Figure 1. Floor plan of North Vancouver Museum Exhibits (Drawn from memory after the visit)

Figure 1. Floor plan of North Vancouver Museum Exhibits (Drawn from memory after the visit)

How objects are collected and documented frequently determine the context they are presented in, yet the use of digital media is transforming how we view, present and perceive collections (Cameron, 2005). The North Vancouver Story included a variety of objects detailing the history of Moodyville, North Vancouver’s logging and sawmill community through its shipbuilding years to its current residential focus. The context presented through the exhibit’s pathway illustrated non-indigenous settlers and the early development of Vancouver. Displays included the traditional presentation of objects with information placards, historic room installations and image slideshow videos supported with narration which a minimal amount of information. The majority of information was factual details about the objects: the use, location and relevance to historic events. I found the juxtaposition, order, quantity and orientation of objects developed a context aside from, or on top of, what minimal factual information was presented.

Manovich argues that databases of [new media] objects can never be perceived as a real narrative experience, regardless of how they are organized (1999). I think this perspective can be applied to the display of real, physical objects when considering narrative as Manovich does: needing both a character and a narrator, the specifically chosen words, the story, and lots of cause-and-affect (ibid). It seems that either developing the traditional structure of a ‘real’ narrative takes more work than organizing the order in which objects are displayed (and may be rarely considered for exhibit displays), or that all objects’ immediate context is not visible on its own that a new context has to be fabricated to connect objects as components of the same, single narrative. Video displays each presented a slideshow of images alongside a verbal storyline of factual information, though were at a very low volume and were difficult to hear when any other person was present. While components of stories emerged through the information, the collection of photographs and information stayed a database of photographs and information, never becoming a narrative form. However, a variety of local people’s stories were presented with a few photographs and objects along one wall. These stories included memories specific to their locations, their childhoods and their families with objects supporting the memory. (For example: ‘By the 1950’s, the pollution was so bad that people didn’t eat the clams anymore…’ and two real clam shells (Leah George Wilson display). The only visitors I encountered were a couple who walked through the exhibits quite quickly, mainly looking at the objects and pictures and rarely reading the display information. They appeared to be local to the area when they commented ‘… Things haven’t changed much, have they?’ in reference to a photo of North Vancouver in 1930 (Visitor observation, 2012). While a true narrative may not be able to be constructed unintentionally, the strength of the North Vancouver Stories exhibit is in the memories that emerge from visitor’s connections to the area that develop a personal context.

Figure 2: 1927 Vancouver Pamphlet in Wilderness on the Doorstep: Vancouver’s Mountain Playground virtual exhibit

In Made in BC: Homegrown Design, objects were presented very similarly to the North Vancouver Story. Many small objects, pictures, magazine cover, posters and a video were displayed in drawers and on the walls. Large objects included a school teacher’s dress from Moodyville and the Exosuit (deep sea diving suit). r’s course reading on BC design. This course pack began with a stunning timeline of BC’s design history, which tied together an understanding of what makes BC’s design unique. Without referring to this hidden-away timeline, the exhibit did not make sense to me. There were many objects and many different elements of design in the Made in BC exhibit, yet none that were related, compared, analyzed or connected in any way. Understanding how these elements could relate engaged me. Seeing some connection between the objects, my experience of Vancouver and the components that made these chosen elements unique and self-sustainable would have engaged me to further explore BC’s design outside of the museum and into my own life.

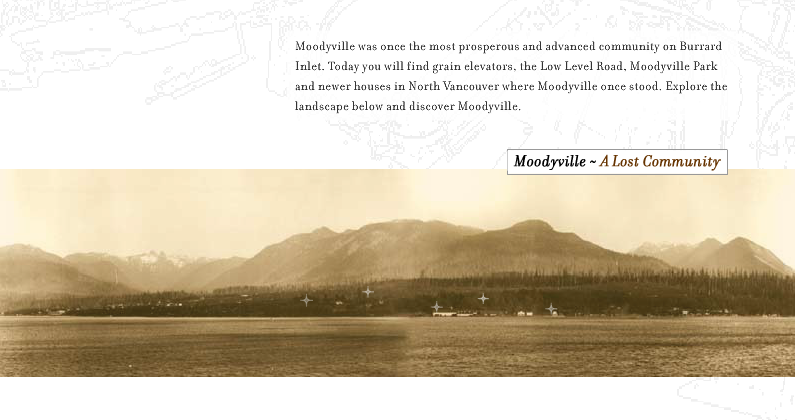

Figure 3. Moodyville: A Lost Community website

Figure 3. Moodyville: A Lost Community website

The 2 virtual exhibits: Moodyville – A Lost Community and Climbing to the Clouds: A People’s History of BC Mountaineering provide options for focus and context interactively. Moodyville was developed by the City of North Vancouver and presents a selection of photographs, information and audio interviews through an interactive website. The website is designed to illustrate the history of Moodyville through information on the sawmill, the town, and the people. Various interaction techniques are used including mousing over for additional information, using up and down arrows to maneuver text, clicking on thought bubbles for audio clips and buttons to pan horizontally for additional information on the present topic. While the connection of information is more engaging than the variety of physical objects presented without broader connections, the website feels like there are many nooks and krannies that contain interesting information, but are not obviously apparent and present a context that feels ‘tucked away’.

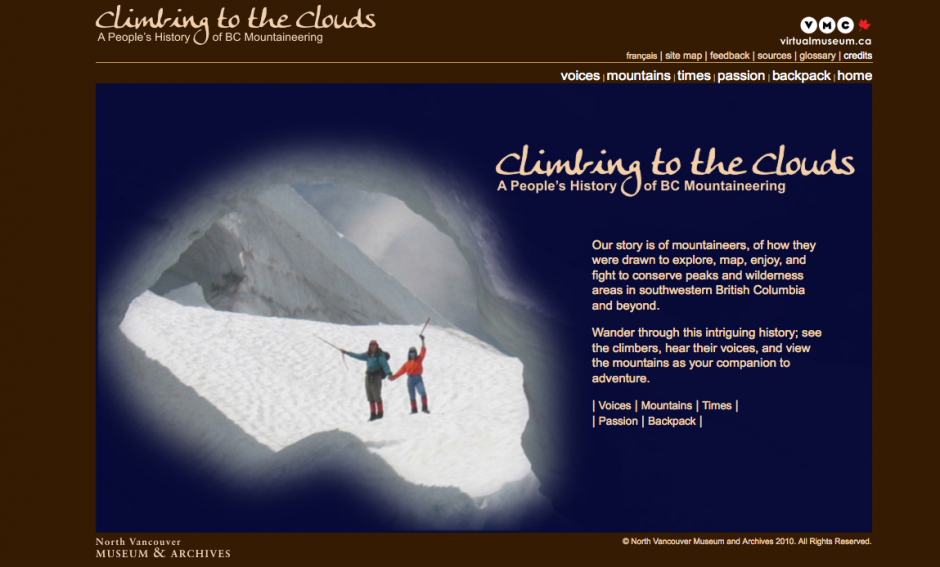

Figure 4. Climbing to the clouds Virtual Exhibit website

Figure 4. Climbing to the clouds Virtual Exhibit website

Climbing to the Clouds is a well-designed, interactive web of stories about adventure and relationships. While the usual selection of objects and photographs are presented, the risk that was involved in explorations comes through the design of the website. The Voices section has many short videos of local mountaineer stories, memories and interviews from a variety of mountaineers central to the exploration of the North Shore mountains (without including any indigenous explorations, summits, or area knowledge). The Times illustrates many events on a timeline with images and information that connect to related topics and people, connecting back to videos from the Voices section. In Mountains, a Google Earth plugin shows the geographic locations of north shore mountains that can be clicked to show images and stories about the first ascents. Passion section is divided into Conservation and Inspiration, detailing people and projects that were inspired by the North Shore Mountains and the adventures they suggest. The Backpack section illustrates objects and practices used while mountaineering in the early days. One interesting story was the use of pigeons to send messages while climbing up Mount Waddington. In the North Vancouver Stories physical exhibit, a small display on hiker’s clothing was presented with photos of a local adventurous couple (the Mundays), with no mention of the virtual exhibit near the display or anywhere in the museum. This connection could have been much stronger since there was space for information, and possibly even a large touchscreen presenting the virtual exhibit in the space, relating it to the physical objects.

Issac provided an example of an exhibit of lithics that was designed based on aesthetics (color, shape, size), which presented a context for the objects very different from only their factual information (2008). ‘as a result, they appeared liberated from their archaeological chronology and had come to represent an artistic objectification of the multiple meanings of these objects’ (Issace, 2008, pg. 296). I found exhibits through the North Vancouver Museum were focused on designing contexts that could easily emerge from a particular perspective on the collection of available objects. This comparison of the North Vancouver Museum and Issac’s lithics example led me to look back at Information Visualization theories to remind myself of how database information manages both focused and contextual views (Ware, 2004). Visualization scholars believe that meaning and stories can emerge from the organization of database information; that it all depends on how information is presented. The presentation of objects create spaces for negotiating context between cultures, audiences and perspectives (Clifford, 1997). It seems to me that physical objects alone afford more meaning and stories than databases, but that the lack of richness in the display obscures object’s integrity. Having the ability to access multiple perspectives, including focused and broad views would allow the audience to develop their own connection between the detailed object and the big picture. I think multiple perspectives and methods of presenting information would have worked well for both physical exhibits at the North Vancouver Museum. By situating detailed objects within a larger context, stronger connections can be developed between objects, eras and stories. Media (creatively designed into the displays) strongly support this presentation method, allowing the audience member to engage with information interactively.

References:

Cameron, F. (2005) Museum Collections, Documentation, and Shifting Knowledge Paradigms. In Parry, Ross (ed.) (2010) Museums in a Digital Age. London and New York: Routledge.

Carlson, K. Visitor Observation, North Vancouver Museum, January 22, 2012.

Clifford, J. (1997) Museums as Contact Zones. In Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Pp.188-219. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

Isaac, Gwyneira (2008) Technology Becomes the Object: The Use of Electronic Media at the National Museum of the American Indian. Journal of Material Culture 13(3):287-310.

Manovich, L. (1999) Database as Symbolic Form. In Parry, Ross (ed.) (2010) Museums in a Digital Age. London and New York: Routledge.

Pamphlet, North Vancouver: Vancouver’s Playground, About 1927, 20th century

© North Vancouver Museum and Archives, http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/Exhibitions/Climbing/, Last retrieved February 6, 2012.

Ware, C. (2004). Information Visualization, Second Edition: Perception for Design (2nd ed.). Morgan Kaufmann.

Website: North Vancouver Museum, http://www.northvanmuseum.ca, Last retrieved February 6, 2012.

Website: Moodyville: A Lost Community, http://www.cnv.org/moodyville/index.html, Last retrieved February 6, 2012.

Website: Climbing to the Clouds: A People’s History of BC Mountaineering, http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/Exhibitions/Climbing/en/c.html, Last retrieved February 6, 2012.