This is an interesting chapter that I really didn’t expect to find in this book. It deals with media differently than we have been for the last couple weeks…or does it?

In Understanding Media (1964), McLuhan defines media as “any extension of ourselves”. For example, the wheel extends our feet, the phone extends our voice, television extends our eyes and ears, the computer extends our brain, etc. It might be more accurate to say that technologies that extend ourselves, are what McLuhan calls media. In this regard, objects of exchange can similarly be seen as technologies that extend ourselves. What they extend are our human relationships. Much like a wheel extends our feet, objects of exchange are extensions of our identity.

Summary:

Much of Graeber’s chapter on exchange can be traced to a seminal work by Marcel Mauss (1925), called The Gift.

In The Gift, Mauss argued that there is a great deal of diversity of economic transactions across human societies, and that all important economic and moral possibilities are present in any given society.

- For example, gift economies, and market economies are not bounded conceptual catagories. They can and often do coexist.

The dominant institutions often end up shaping our perceptions of humanity. Our western notion of “man as an “economic animal” is made possible by certain specific technologies (money, ledger sheets, mathematical calculations of interest) which we then generalize to reveal the hidden truth behind everything—but the existence of such technologies proves nothing” (Graebner 2010a: 3).

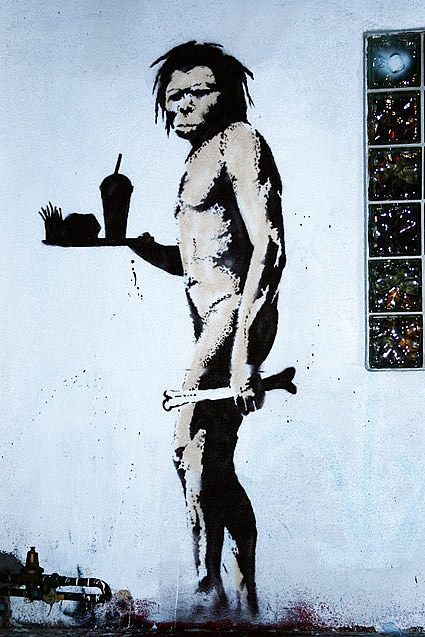

Banksy, Homoeconomicus, LA

Banksy, Homoeconomicus, LA

In contrast to homoeconomicus, anthropologists in the early 20th century found that rather than being based on barter, and gain, most non-western economic systems resembled our interactions with friends and family outside of the impersonal sphere of the market. Of most importance were personal relationships. Marcel Mauss called these “gift economies” (2010b:220)

“…a gift economy is one in which wealth is the medium for defining and expressing human relationships (Gregory 1982).

Graeber notes that “The Gift” is mistakenly treated as if it were one thing, one non-commercial transaction. When, in actuality, it is a wide variety of different kinds of non-commercial transaction that operate according to different principles.

He has developed what he calls fundamental categories of economic transaction

- These are fundamentally different moral logics that lie behind phenomena that we class together as “the gift” (2010a: 4).

Communistic Relations

- “from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs” (2010b:220). Here, Graeber is not discussing a Communist political/economic system, but base social relations that exist in every society.

- Giving directions to strangers, knowing that they would likely do the same for you

- Helping a baby that has fallen on the tracks if you are able.

- Plumber says hand me a wrench to his assistant —and rather than say what do I get for it, he does it.

- These relationships are taken to be eternal. You don’t keep a ledger of the wrenches you’ve handed out or the directions you’ve given.

- You expect that similar “gifts” will be returned and the relationship is seen as eternal

Reciprocal Exchange

- Based on a fundamentally different sort of moral logic. This exchange is all about equivalence.

- Exchange is about the goods, although there has to be a minimal trust (relationship) to carry out the transaction at all…unless dealing with a vending machine.

- Exchange is not permanent, ledgers are kept, if only in the mind, and debts can be cancelled along with the relationship

- Cancelation of the relationship is often not the end game, at least not when dealing with people you know.

- A tit-for-tat usually ensues and as long as equivalence is not reached a relationship continues

- Economists maintain that parties in this type of exchange try to get as much as they can out of the deal (homoeconomicus)

- Anthropologists have long pointed out that when dealing with the exchange of gifts, i.e. exchanges where the objects passed back and forth reflect on and rearrange relations between people, competition works in the opposite direction.

- Contest of generosity where people show off who can give more away

- Anthropologists have long pointed out that when dealing with the exchange of gifts, i.e. exchanges where the objects passed back and forth reflect on and rearrange relations between people, competition works in the opposite direction.

Hierarchical Relations

- Exist between parties where one is socially superior and they do not operate through reciprocity at all

- Works by a law of precedent

- If you give money to a beggar, then he will expect the same amount next time. Same goes with a charity

- Passing superior status to a former inferior

- A serf’s gift to a feudal lord is treated as a precedent (what will be expected next time)

- Assumes a permanent relationship

Univ.Pennsylvania Museum, 1899. Unknown Photographer.

These principles always coexist… “It is hard to imagine a society where people were not communists with their closest friends and feudal lords when dealing with their small children” (2010b: 222).

Graeber (2010a) questions why, then, do we fail to notice the coexistence of these principles, and our ability to move back and forth between them?

- His answer is that when we think of society in the abstract, and when we try to justify social institutions, we ultimately fall back on a rhetoric of reciprocity

- “When trying to imagine a just society it is hard not to evoke images of balance and symmetry, of elegant geometries where everything cancels out”

The market is exactly like this: “a purely imaginary, abstract totality where all accounts ultimately balance out” (Greaber 2010a:13)

The final sections of Graeber’s (2010b) chapter focuses on the origins of currency, and a world (Eurasian) history of the development of money. Of most interest here is that money originates as a token of recognition for a debt, and often a debt that cannot be repaid (224). In this sense, it originates as a medium of expression of the importance of social relations. At some stage, and Graeber himself admits to speculation here, the token of this very important debt comes to possess a power of its own, and even comes to be seen as a source of its own value. With this new ability, money inverts its original purpose and becomes a way of creating new social relationships (224), rather than a recognition of existing social relationships. Once these tokens become a full blown currency “it allows for the definitive transfer or alienation of what is bought and sold” (2010b: 224). Graeber feels this is a moral crisis.

Work Cited:

Graeber, David. 2010a. On the Moral Grounds of Economic Relations: A Maussian Approach. Open Anthropology Cooperative Press.

—–2010b. Exchange. In Critical Terms for Media Studies. Eds. W.J.T. Mitchell and Mark B.N. Hansen.

Gregory, Chris A. 1982. Gifts and Commodities. New York: Academic Press.

Mauss, Marcel. 1990. The Gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies. New York: Routledge.

Leave me a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.