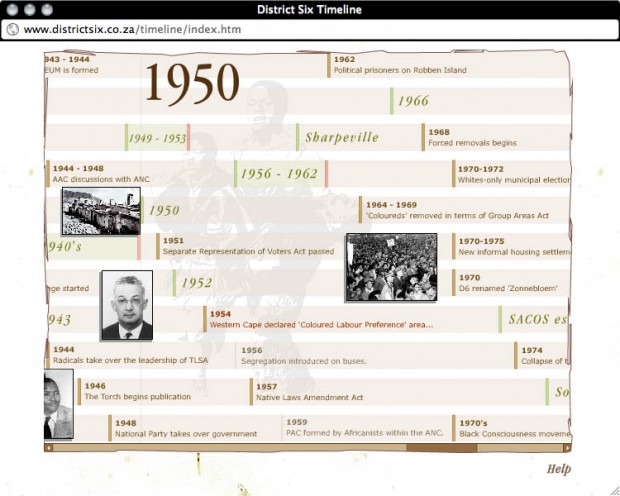

Abungu (2010) paints a picture of the contemporary museums in post-colonial Africa as working to move away from “the old style of exhibition (eg. Dusty objects hidden in glass cases)” (181), and to address the changing face of African society that museums now represent. Part of decolonization, she argues, is a move away from a western museum model, and the positioning of the museum as a tool for social and cultural development. Capetown’s District Six Museum, for example, represents a shift from a focus on objects to the memorialization of the atrocities committed under apartheid––a move from exhibiting tangible heritage to featuring, promoting, and actively documenting and communicating intangible heritage in digital form. Digital cultural heritage from her perspective has the potential to be an agent in the social and cultural work of the museum, telling stories formerly denied heritage value by an oppressive regime, breaking down walls of institutions and creating access for the marginalized; at the same time, its reach is limited by aging telecommunications infrastructure, lack of access to Internet and computers, and conditions of poverty. Abungu’s article points to the role of new media in facilitating access to digital cultural heritage (see Christen’s 2009 piece, and my piece (2009) assigned for this week as well) and the challenges of access outside of urban centres.

Abungu (2010) paints a picture of the contemporary museums in post-colonial Africa as working to move away from “the old style of exhibition (eg. Dusty objects hidden in glass cases)” (181), and to address the changing face of African society that museums now represent. Part of decolonization, she argues, is a move away from a western museum model, and the positioning of the museum as a tool for social and cultural development. Capetown’s District Six Museum, for example, represents a shift from a focus on objects to the memorialization of the atrocities committed under apartheid––a move from exhibiting tangible heritage to featuring, promoting, and actively documenting and communicating intangible heritage in digital form. Digital cultural heritage from her perspective has the potential to be an agent in the social and cultural work of the museum, telling stories formerly denied heritage value by an oppressive regime, breaking down walls of institutions and creating access for the marginalized; at the same time, its reach is limited by aging telecommunications infrastructure, lack of access to Internet and computers, and conditions of poverty. Abungu’s article points to the role of new media in facilitating access to digital cultural heritage (see Christen’s 2009 piece, and my piece (2009) assigned for this week as well) and the challenges of access outside of urban centres.

Abungu’s analysis of the museum in post-colonial Africa speaks to Fiona Cameron’s assertion that heritage discourse––which has come to include digital heritage––is culturally and politically produced. She argues:

“Choices as to what to keep and criteria in which to define objects are made at the expense of others and as Hall (2005) suggests is one of the ways a nation slowly constructs a collective memory of itself. Clearly the same is true for digital heritage items. The value of the past for the future and the nation hinges on these essentialized meanings” (Cameron 2008:177).

Reminding me of Jeremy’s post last week, Cameron argues that Western societies have been largely object centered, “where notions of heritage place the accumulation of objects of critical importance is the transmission of cultural traditions” (Cameron 2008:178). She contrasts this object-orientation with societies that are concept centered, in which objects are preserved because of their ongoing functionality, and in which cultural is transmitted orally––what is now known and codified by UNESCO as the intangible cultural heritage. As tangible and intangible heritage are being digitized in the name of preservation, they are rapidly being inducted in a process of “heritigization”, which Cameron sees as reinforcing Western paradigms of historical materiality (think Walter Benjamin). This process of heritigization is further steeped in the discourse of loss, in which digital heritage is valued if it is perceived as being lost to posterity, rather than for its value in the present. What are the consequences? Should heritage preservation be about more than the archiving of a record, of documentation, of an object? What is the role of the digital object in heritage preservation, and in keeping intangible cultural heritage alive and reproducing? How do we understand the digital surrogate in relation to the original?

Alonzo Addison (2008) reflects on the need to safeguard heritage’s endangered digital record through the lens of built-heritage documentation. By his definition, virtual heritage is practice oriented: “the use of digital technologies to record, model, visualize, and communicate cultural and natural heritage” (2008:27). This work is producing digital heritage, which itself is threatened by changing technologies, data storage challenges, and a lack of interdisciplinary collaboration and cooperation. Addison’s work, scanning and digitally documenting endangered world heritage sites, is grounded in discourse promoted by the UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, which “formalizes the concept of places of ‘outstanding universal value’ to all humankind and proceeds to encourage their protection and preservation for all” (2008:30). (Note that intangible cultural heritage was only formalized as a heritage concept in 2003). As you can see in this message from the Irine Bokova, the Director General of UNESCO, on the 40th Anniversary of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, the discourse of universal value is alive and well (but of course depends on ongoing international support. Lack of support makes even more visible the ideological underpinnings of world heritage policy…). World Heritage, according to UNESCO, “is a building block for peace and sustainable development. It is a source of identity and dignity for local communities, a wellspring of knowledge and strength to be shared. In 2012, as we celebrate the 40th Anniversary of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, this message is more relevant than ever.”

Addison’s chapter is well illustrated in this recent TED talk by Ben Kacyra (below), who has developed technologies for extremely fast, high resolution 3D scans of heritage spaces, and is currently building a global network with the goal of scanning and documenting all of the world’s endangered heritage. He reiterates that the loss of world heritage––heritage that essentially belongs to us all as humans on earth––is a loss of the stories (the intangible) that these places represent, and a loss of the collective memory that tells us who “we” are. Without our heritage, he asks, how will we know who we are?

I am interested in one particular moment in the talk, when he describes how the scanning and digital modeling of a ritual structure in Uganda was put to use after the original structure burned down. In this case, I see potential for intangible cultural heritage–the knowledge of how to build a traditional form of architecture––to actually be revived with the use of digital documentation. Because of the 3D model, the structure could be rebuilt, and in the course of doing this, new knowledge was generated, and potentially passed on. So, what is the relationship of the digital file to the original? In this case, the digital file could be used to recreate the original, but most of the scans by CyArk will simply be archived. What will be documented along with them? Are they removed completely from their contexts of production—do they maintain a connection to the original or do they take on new heritage significance on their own?

Finally, Last week we discussed the news that the US Library of Congress will begin to archive all tweets being generated through the platform Twitter. The response to this announcement is interesting, coming from those who are eager to be able to search the archive, to those who feel that their privacy has been invaded (I never signed up to be archived by the Library of Congress!), to those who think that archiving more than 50 million tweets every day is a colossal waste of financial and human resources. The New York Times discusses a new kind of researcher—the twitterologist––and indeed, the data is tremendously useful for researchers of all kinds, but is it heritage? Why or why not?

Lyman and Besser (2010) discuss the Internet Archive as representing another example of the desire to preserve and archive as much of the emerging digital heritage as possible, before it is “lost”. Through the Wayback Machine, over 150 billion web pages are available, reminding users of the dynamic and contingent nature of the Internet—it is always changing, or more accurately, we are always changing it. Is it heritage?

What heritage should be saved? Who should save it? Does documentation of heritage amount to preservation, to ‘safeguarding’? How is local heritage translated into heritage of “universal value”, and what are the implications? What of the question of cultural property, of intellectual property rights, and copyright in this mess? I like Larry Lessig’s TED talk, in this regard, for the way it spells out some of the legal and cultural foundations of current IP and copyright law. But, to connect a thread back to some of our earlier conversations, what are the some of the ethical issues related to digitizing and making formerly analogue heritage digital—should digitized cultural documentation automatically be inscribed as heritage of universal value, that should be open for access by all… or can we come up with alternatives that contest this emerging norm?

There is clearly a lot to discuss in the seminar this week, from digital cultural heritage as access, as documentation, as ethical and legal touchstone, as cultural policy, as memory and identity, to its representation of shifts in relations of power… I look forward to your thoughts on this post or any of the readings for this week.

References Cited:

Abungu, Lorna (2010). Access to Digital Heritage in Africa: Bridging the Digital Divide. In Museums in a Digital Age. R. Parry, ed. Pp. 181-185. London and New York: Routledge.

Addison, Alonzo (2008). The Vanishing Virtual: Safeguarding Heritage’s Endangered Digital Record In New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage. Y.E. Kalay, T. Kvan, and J. Affleck, eds. Pp. 27-39. London and New York: Routledge.

Cameron, Fiona (2008). The Politics of Heritage Authorship: The Case of Digital Heritage Collections. In New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage. Y.E. Kalay, T. Kvan, and J. Affleck, eds. Pp. 170-184. London and New York: Routledge.

Christen, Kimberly (2009). Access and Accountability: The Ecology of Information Sharing in the Digital Age. Anthropology News (April):4-5.

Hennessy, Kate (2009). Virtual Repatriation and Digital Cultural Heritage: The Ethics of Managing Online Collections. Anthropology News (April):5-6.

Lyman, Peter, and Howard Besser (2010). Defining the Problem of Our Vanishing Memory: Background, Current Status, Models for Resolution. In Museums in a Digital Age. R. Parry, ed. Pp. 336-343. London and New York: Routledge.

Great to see a mention of my previous post, Kate 🙂

I will be replying to this with some citations later tonight when my Son goes to bed…

Hello there class,

Finally, I have enough space from my son (now that he is in deep sleep) to comment a bit about Kate’s post here.

There are a few points I would like to make and I will do my best to make this flow in some coherent manner.

Kate, you have defined “Virtual Repatriation” (Hennessy 2009:5) as something that involves VISUAL access to a digitized cultural heritage but is this definition wide enough?

As anyone can access the internet, I would imagine that repatriation would also allow the originating community to store the virtual information and be the exclusive gatekeepers of access. Also for virtual worlds, one gains access through virtual embodiment and not just visual access.

Is someone like Addison suggesting that access rights itself should be preserved since it is occasionally about “making something new”?

I am guessing that the need for the degree to which heritage should be archived (as mere documentation or something more) can be determined by the particular Gatekeeping Nation and by the demographic needs of the museum/gallery audience.

Privacy settings and other ethical protocols could be reached through a consensus between parties. However, this does mean that the bureaucracy goes against the freedom the internet provides but perhaps not everything needs to be made public if particular indigenous cultures feel completely disempowered as a result.

This seems to be the “common sense” part to me but the part that is much harder to rationalize is what to do if the Nation in question really does not want ANY representation or exploration by others on the internet – especially those outside their culture?

For those societies who seem unwilling to negotiate their initial entry into cyberspace, both parties will need to face the consequence that there is no guarantee their civilization will ever be remembered by others thousands or millions of years down the road.

This seems to be the feared loss Kacrya was speaking of when he articulated his urgency to digitally scan every epic cultural artefact on this planet.

Some cultures may even be perfectly comfortable with their occult knowledge being buried with them – as was with the fabled Atlanteans (assuming they ever even existed – which we cannot verify)…

I just keep on thinking about all the censoring (sometimes at the last minute or in realtime) that can take place and this process will ultimately be seen by many as completely prohibitive and a disincentive for others wanting to remember a civilization – unless it is their own.

The main worry is that the general public – outside of these cultures – have become fickle due to the near infinite amount of cultural distractions available to them online.

Seeking immediate gratification, many may be dissuaded by this heavily restricted access to ever want to be curious about such stories and cultures again…

In some cases, some tribes would prefer to not have any outside involvement or interest with their secret stories and rituals…

It is a catch-22 though because if we were to exclude promoting these cultures since it seems to be too much effort and hassle from our perspective, we would also come across as racist and exclusive by the very same cultures that insisted we restrict access to their content to the point where net-users felt a better use of their time was exploring a more openly-available culture.

In an era of constant distractions, it is already a relatively hefty cognitive effort to even choose to visit these webpages in the first place. So, we may lose the imperative and collective will to historically archive such cultures for future generations should they ever disappear from all of civilization for some reason or another.

When cultures make contingent editorial decisions due to “re-dreaming” (Cristen 2009:4) in real-time, they need to be made aware in advance that Google and the Wayback Machine will auto-cache all the original files and so what has once been made public, will remain public virtually forever.

This is precisely what happened with your Doig River website. The Wayback Machine (and probably Google Image search) auto-cached the first images of the drum (Hennessy 2009:6) being publically shown and then there was regret but no turning back.

There needs to be a museum protocol and command-line in the programming code that can resist caching to google image searches and the Wayback machine. Maybe this occurs in the code as a function-call that specifically blocks auto-caching from the Wayback Machine and Google. Maybe Bardia has a particular function-call in mind for this?

***Mild topic change***

As sexist/racist as this sounds to Western culture today, some Gatekeeping Nations may require a user-ID to ensure the gender/race of the viewer is appropriate to culturally view certain materials…it would be nice if there was a disclaimer explaining to the user why this material is exclusive this way though. The Waraumungu did this on Christen’s website and naturally, this would thwart a user’s experience. This information could be password protected.

Unfortunately, I could see many “re-dreaming” nations turning down the intial offer to be archived at all for this reason of being permanently exposed on first (virtual) publication. Therefore, the important aspects of their ontology may forever be buried within their own culture. Perhaps, this is not a bad thing ultimately. Maybe we are never meant to know certain ritual secrets – maybe they are meant to die with its originating civilization.

This is not to say that I foresee these civilizations as being on life-support the same that colonial anthropologists saw First Nations cultures in the 19th and early 20th centuries. All civilizations (like Atlantis) eventually meet their demise sooner or later. It is an idea to have some kind of cultural contingency plan, unless cultural survival is not part of the culture’s ontological narrative.

Maybe some cultures can password-protect their secrets and can only be decrypted once a certain seal has been broken (that foretells the official death of a civilization) – such protocols could be made in advance by the original civilization in parternership with a hosting institution.

I am thinking of a mutually agreed cross-cultural last will and testament.

Ok, on a lighter note, thanks for mentioning my post when Cameron talks about how Western societies have been largely object-centered, rather than concept-cenetered…

I should clarify how in the example of Dr. Fate from the 1980s, that purchased action figure gave permission to activate the concept. Also, the ritual begins with the concept (comic-book and advertising memes) and is anchored/activated once the figure has been purchased and possessed. So in this case, I am not entirely sure if this ritual is completely “object-centered”. Even with an object-centric culture, as soon as an internal narrative is involved, the concept becomes just as important in the exchange.

I would say that purchased objects such as action figures merely cause our culture to “re-dream” the narrative and give this dream its token power. On that note, I am equally as curious as you about whether that 3D-digitized Tomb render in Uganda will have some residual ritual power.

Ok, I cannot help myself but end this post with a bad video game pun – “Renders of the Lost Tomb”…hahahahahah 😉 Here is the reference – http://www.gb64.com/game.php?id=6401

Clearly, it is my bed time now.

Reflecting on this weeks readings, and your post, Kate, I’m reminded of a talk I attended in the fall through the —“Keep Calm and Carry On or Freak Out and Throw Stuff; The Public Library Moving Forward”. Paul Whitney, the former City Librarian of the Vancouver Public Library, spoke about a very different kind of “loss” (Cameron 2008) and very different set of problems with “bridging the digital divide” (Abungu 2008)—the crisis of the public library. While large institutions in relatively affluent cities have been able to keep up (http://www.vpl.ca/electronic_databases/cat/C88), to subscribe to many digital archives and purchase digital book licenses, small town libraries throughout North America (and the world) are closing, and in large part (he argued) due to the availability of cheap, downloadable digital books and text (not to mention the perceived uselessness of entire sets of Encyclopedia Britannica). Public libraries in small towns that have remained open are often unable to afford subscriptions to digital journals and books. Outside the university system, he made the situation sound quite dire.

I think the case of public libraries presents an interesting set of issues given this week’s topic. In Peter Lyman and Howard Besser’s article, they ask “Should commercial, proprietary concerns legally override the obligation of copying for the sake of preservation?” (Lyman and Besser 2010, 338). I would add, “or for the sake of public access?” As one council in the UK has decided, public libraries (and therefore providing copies of books and resources to the public) are perhaps a legal right (http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2011/nov/16/court-challenges-against-library-closures).

Likewise, Larry Lessig’s talk (thanks for that link, Kate!), argues that:

“Now in response to this new use of culture—using digital technologies– The law has not greeted this Sousa [here he’s referring to the ways ordinary people are given back their “voice” through the creative use of digital technologies] revival with very much common sense. Instead the architecture of copyright law and the architecture of digital technologies as they interact have produced the presumption that these activities are illegal. Because if copyright law at its core regulates something called copies, then in a digital world, the one fact we can’t escape is that every single use of culture produces a copy. Every single use therefore requires permission. Without permission you are a trespasser . . . Common sense, here, though, has not yet revolted in response.”

As Jeremy noted, often “bureaucracy goes against the freedom the internet provides”. As in Abungu’s paper, although here in a very different context, the digital availability of resources is spread differentially; rural and small town populations without university membership are excluded from much of the access often theorized as ubiquitous.

As with museums, we might ask what the role of public libraries in a digital world should be. Most libraries, Paul Whitney noted, now rent more movies than they loan books—but this, too, is changing, as more and more of the public download digital content (as Larry Lessig says, “ordinary people live life against the law”) or subscribe to Netflicks. But when libraries close, the public rarely mourns the loss of video collections. As a “threatened species” (http://www.publiclibrariesnews.com/), it is the loss of access to books and local heritage that is couched in a “discourse of loss”, to use Cameron’s language. As Christen says, questions of access are “part of deeply social and ethical relations people have to and with ‘information’ (2009, 4).

As Larry Lessig advocates in his TED talk, Paul Whitney likewise seeks solutions by asking authors, publishers, and institutions to enable freer content. Whitney has been reseraching eBooks and “Public Lending Right” in Canada for the Public Lending Right Commission, and is attempting to gain approval for a World Intellectual Property Organization international treaty on limitations and exceptions for libraries. Following the sentiments laid out by Christen, more authors are making their work available through open access publishing. Digital databases like Project Gutenberg (http://www.gutenberg.org/) offer public access to out-of-copyright texts. Yet if the public is going to have access to current books or articles, it will be up to companies like Amazon to offer public libraries contracts with looser (and cheaper!) terms of use.

References Cited:

Abungu, Lorna (2010). Access to Digital Heritage in Africa: Bridging the Digital Divide. In Museums in a Digital Age. R. Parry, ed. Pp. 181-185. London and New York: Routledge.

Addison, Alonzo (2008). The Vanishing Virtual: Safeguarding Heritage’s Endangered Digital Record In New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage. Y.E. Kalay, T. Kvan, and J. Affleck, eds. Pp. 27-39. London and New York: Routledge.

Cameron, Fiona (2008). The Politics of Heritage Authorship: The Case of Digital Heritage Collections. In New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage. Y.E. Kalay, T. Kvan, and J. Affleck, eds. Pp. 170-184. London and New York: Routledge.

Christen, Kimberly (2009). Access and Accountability: The Ecology of Information Sharing in the Digital Age. Anthropology News (April):4-5.

Lyman, Peter, and Howard Besser (2010). Defining the Problem of Our Vanishing Memory: Background, Current Status, Models for Resolution. In Museums in a Digital Age. R. Parry, ed. Pp. 336-343. London and New York: Routledge.

Thank you, Dr. Hennessy, for the tightly woven mix of theory, hyperlinks, and audio-visual material to illustrate and support the readings. The bar is getting higher…yikes…

Re: Jeremy’s post. I think he makes a good point about how access to digital heritage is often construed in the literature as “visual”, which may indeed be a bit too narrow from a phenomenological perspective. Cameron (2008) also makes this point and perhaps traces some of its origins when discussing “object-centered” notions of heritage in perspectives such as Jonathan Crary’s (p. 178). I had noticed that most of the readings seem to overlook that the production of digital heritage they are discussing is primarily vision-based, or rather, that they are discussing it with the assumption that it should be. In fact, it is surprising that this has not been more critically discussed because I think Crary has made some really good points in his writing. This “vision-based” epistemological paradigm may be the language of science and of institutions that use scientific rhetoric to legitimate their power (Latour and Law have extensively written on this point), but from a grass-roots point of view, does vision really define digital (and non-digital) experience? Scholars often take for granted that the world they live in is the world that everyone lives in, and I am the first person to admit that I must constantly check myself to not fall into that trap because the danger of that is to limit not only our fields of inquiry but also possible new ways of seeing and of being.

More on Jeremy’s post: Jeremy discusses how “important aspects of their [nation’s] ontology may forever be buried within their own culture. Perhaps, this is not a bad thing ultimately. Maybe we are never meant to know certain ritual secrets – maybe they are meant to die with its originating civilization.”

I agree with the latter statements. I have a very personal view on this. It may not go down very well with my fellow classmates, but may I burn in hell for being who I am…and saying it…so here it goes: I find that the current trend (obsession) with archiving and preserving every little bit of digital and non-digital piece of information that is “culturally” produced is 1) utopic and unrealistic from a resources and material point of view; 2) therefore, misleading and thus quite rhetorical in character; 3) reifies one of the most salient issues behind the digital preservation of cultural heritage, namely, who owns the means of production (this, of course, would be a Marxist view)? 4) promotes and reinforces practices that commodify culture.

Let me unpack this in a somewhat chaotic way…there is method in my madness…

Many of our readings eloquently describe the issues around the importance of this preservation process and although they do raise the points I mention, in the end, they support a process that is essentially ideologically driven by basically breaking it down to how can WE do this to the advantage of OUR community (with a kumbaya-like allusion to the fact that WE signifies the global community, universal values and universal love). In effect, the scholarship itself reproduces hegemonic processes that reinforce a hierarchical reading of power based on purely materialistic values and the commodification of culture in a globalized world. It is useful to remember that the term “globalization” refers, first and foremost, to an ECONOMIC reality: the globalization of markets and trade that began with the spice trade and silk routes but only really took its full institutional form in the 19th c.

There are numerous passages in Lyman and Besser (2010) that evoke how the preservation of our “vanishing memory” (don’t get me started on that one coz’ I did a whole argument on the concept of the trope of “collective memory” in my MA thesis and would be happy to rehash it in class…) is problematic from the perspective of keeping up with a profit-driven globalized “culture”. To name a few, p. 339, para. 3 discusses the difficulty of keeping up with constantly changing file formats; p. 342, paras. 3 and 4 suggest that market-based practices of planned obsolescence with regard to digital technologies are one of the big obstacles to digital preservation; p. 343, para. 2 outlines the tension between the principle of “public good” vs. the principle of the “electronic marketplace” (gee, I wonder which one will prevail?). Addison (2008) also examines some of these technical points.

At the risk of being even more unpopular, I would admit that I actually have no interest in absorbing every little bit of data that exists. In fact, I am one of those freaks who deeply believes that less is more. I would rather read less but read it in depth. I would rather talk less (or write less) and write something that is relevant.

Nicholas Carr (2008) wrote a wonderful article on the difference between depth of knowledge (and experience) and breadth of knowledge (and experience) in reference to new media, specifically Google. He quoted Richard Foreman (para. 37):

“As we are drained of our “inner repertory of dense cultural inheritance,” Foreman concluded, we risk turning into “‘pancake people’—spread wide and thin as we connect with that vast network of information accessed by the mere touch of a button.””

I think that one of the biggest delusions that we currently live in, especially with regards to new media, is the fallacy that “having” equates “knowing “ or even worse, “experiencing”. Thus we buy all kinds of electronic devices and accumulate all kinds of data on our hard drives or in our clouds with the idea that it makes us smarter, stronger and more connected. But can buying the fanciest photographic camera on the market make me a good photographer? Many people believe it does. I personally don’t see the correlation. Similarly, I question whether preserving “heritage” data makes people more culturally connected? On this point, I would be happy to expand in class, but just as a teaser, let me just ask:

Why should we remember everything? Indeed why should we remember events, people and places that we have never even directly experienced? How important is it to keep ritual alive by freezing it into data? Is not the strength of oral cultures and traditions the fact that knowledge is passed down as something expressed through the fluidity of face-to-face communication with all its “imperfections”?

Digital media for me has appeal BECAUSE it is a medium that tends to renew its contents which is in constant flux. To use it to fix data seems to me as strange as cryonics (freezing dying people to preserve them in a future where they could be brought back to life). It is an obsession with holding on to matter; it is a fear of death that we try to ward off by accumulating rather than letting go. A misguided apotropaic practice because it is killing the planet, our resources, our souls.

I will quote my favorite author, who would be grossly unpopular in today’s North American scholarly circles:

“And how, without being blinded by I know not what prejudices, dare one claim that material superiority compensates for intellectual inferiority? (Guénon, 1925, p. 21).

In my own view, the accumulation of material “heritage” can in no way compensate for a lack of intellectual depth that comes with surfing over images and consuming culture like one would eat fast food. What good is it to preserve everything if I have FORGOTTEN how to truly engage with culture? If my new epistemology is to “skim over” things without taking the time to incubate them and know them intimately? If my knowledge of African cultural heritage is based on my online experience?

Here I must quote a line from Abungu (2010) which left me speechless because of what it was saying (I’ll let you figure out what I mean by that):

“AFRICOM in its new form seeks to contribute to the positive development of African societies by encouraging the role of museums as generators of culture and as agents of cultural cohesion.” (p. 184, para. 6).

Using digital media to accumulate “heritage” can only make the commodification of culture worse. It is my view that the true power of digital media is to allow us to communicate, and live, in the present. To be in constant production and transformation rather than living in an “information overload” of the past. I deliberately not addressing issues of access here, but would happy as a pig-in-shit to debate all this with you in class, my dear fellow classmates because…I value your opinions and wish to engage with you in face-to-face communication…what can I say? I am a bit old school…

Sources included this week’s readings and these additional sources:

Carr, N. (2008, July/August) Is Google Making Us Stupid? What the Internet is doing to our brains. The Atlantic. Retrieved on January 6, 2012 at http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/07/is-google-making-us-stupid/6868/

Guénon, R. (1925). Oriental metaphysics. Text of a lecture given at the Sorbonne in Paris on 12 December, 1925. Retrieved on January 6, 2012 at http://www.worldwisdom.com/uploads/pdfs/27.pdf

Wow! Once again, all of these posts are packed full of great ideas, all of which I would happily devote all of our conversation tomorrow.

Let’s start with the District Six Museum, which is a really interesting window onto Apartheid’s history. I think it’s important to note that District Six was a unique neighborhood in Cape Town, and emblematic of exactly what the Apartheid regime did not want: a space of ethnic and cultural mix. The neighborhood, as I understand it, consisted of Africans, Coloured (the South African term for an individual of mixed heritage, i.e white and black), Indians, Malays, and other ethnicities. The Apartheid regime bulldozed the entire neighborhood and moved each ethnic group to segregated locations. When I was in Cape Town in 1999, there were still rubble there. I mention all of this because I think it is important to point out that much of what was tangible in District Six was destroyed; what remained of was primarily intangible. I assume that this has something to do with its focus on intangible heritage. I was kind of surprised that Abungu did not mention the history of the location at all.

The loss of a location like District Six, and the forced relocation of the inhabitants reveals the importance of questioning who gets to decide which heritage, and by what means, are preserved. Cameron writes, “Heritage is deemed to signify the politisation of culture and the mobilization of cultural forms for ideological ends” (171). As Kate pointed out, Cameron tends to align the ideologies behind “heritagization” as particularly Western, yet I think James Clifford problematized such thinking in “Museums as Contact Zones.” It is never just the forces of one dominant culture, but a continual process of negotiation across cultures that produce the ideologies that promote heritage. That said, it is clearly an asymmetrical power dynamic by which Western (i.e. Colonial) powers have a significant, productive, role in the determination of who, what, and where deserves to be “heritagized.”

This is something that I really enjoy about the decision by the Library of Congress to attempt to capture all of the Twitter-stream; it is weirdly democratic. Tweets about someone’s cat will be recorded at the same time and method as the President of the US. I find that interesting. I think in the end, capturing everything from Twitter is probably easier than trying to sift through the onslaught of information. Future researchers can figure out what is valuable, or not.

I’ll end with a couple of comments on previous posts.

Jeremy, I am not certain that I agree that the digital objects we have read about are purely visual. I think that they are more catalog, database, oriented than visual. Much of what we have read has focused on the value that digital objects provide through their ability to have multiple cultural interpretations attached to them. The repatriation, in my view, is the ability to contextualize the object based on one’s cultural understanding of the object, to add to the understanding of a specific thing. The visuality is really a referent to the thing back in the museum. I don’t think that we should underestimate the power of writing about one’s culture. Besides, this isn’t limited to writing. Songs and stories can also be recorded in many of the digital systems we have read about, so I don’t think we need to focus on the visuality.

Also, I don’t know that the internet is itself inherently free, in fact I would suggest that it is not. It requires participation in our capitalist system: paying for access, for instance. It is built on a number of infrastructures that are funded by the taxpayers of different municipalities and nations. I guess I’m trying to say that the internet always was a bureaucratic entity, for better or worse. Though, I have to admit they do a pretty good job at mucking up the freedom parts.

Claude, I would argue that the Carr article in question begins with the assumption that culture doesn’t change, or at least shouldn’t. Much of what he suggests about the internet, and Google, is cultural bias. Ways of reading, ways of thinking—these are not inherently good just because we have built our culture on them. They have also shifted dramatically with other technologies in the past—the printing press, television, radio all impacted our culture in their own way. That the internet is potentially changing our relationship to information, and may have larger effects, is neither bad nor good, I would argue. It just is.

Okay, Tyler. I will be the first to admit that I may be turning into a stodgy old grump who is always complaining about how the younger generations have no respect for the “old ways” of the older generation (to which I now belong too…yikes…).

LOL. Point taken. It is indeed an epistemological shift.

But I am nostalgic of the days when I did not suffer from information overload…

Hey Tyler, I agree with you about the repatriation being more than visual.. I was responding to a direct quote from Kate’s own article when she equated “virtual repatriation” with “visual access” (her words)…I guess I was asking her if she meant anything more than merely the visual.

Now, I will take it easy as I have just submitted my (password protected) response paper assignment to this blog 🙂

Looking forward to seeing all of you tomorrow.

-Jeremy

Wow – I will need to respond in multiple *short* posts this time.

In response to archiving digital information and its references to heritage: I will again talk about dance.

Dance is an art form that is very difficult to notate, realistically record, analyze, copywrite or really steal. Dancers have always had a suspicion around digital technologies: that they will obscure the important kinesthetic knowledge of the dancer or audience member, or that the act of live performance will lose its ethereal nature when it can be recalled like a tv show with TIVO (I assume there is a newer-version of recording, but I’m not very aware of tv technology…)

Gina Gibney Dance and Dance/NYC created a series of video screenings titled: ‘Sorry I missed your show’ in order to see performances by established and emerging choreographers. While this was a unique opportunity to see visual and audio documentation of a performance, discussions were held around the value of viewing documented dance instead of the live show alongside critical discussions of the works.

http://dancingperfectlyfree.com/2010/07/27/sorry-i-missed-your-show/

In response to Claude’s #4 point that it encourages commodification of culture, many of the performing arts are resisting any commodification of their unique and physical ideas. The authenticity and aura IS this experience, received through all possible physical senses. Having only a visual representation is not enough. Many performers are even upset with using projections onstage. There is a strong debate around how to use projection so that it doesn’t detract from the physical performer, which it almost always does.

I’m still not sure which side I want to be on: whether a history of dance can survive without documentation and whether intangible knowledge should stay intangible.

However an example of stealing dance is here:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/stage/2011/oct/10/beyonce-dance-moves-new-video

Basically, Beyonce’s viewed many European contemporary choreographies for ‘research’ and ideas, but instead of using the ideas she directly reproduced the dances in her music video ‘Countdown’ without reference or permission. There was a bit of a scandal after the fact, but de Keersmaeker was nice enough not to press charges (not that she really could have, financially).

Jeremy’s suggestion of only allowing certain demographic’s access to documentation could work – but becomes very complex in itself. Beyonce is a performer – wouldn’t that give her access to other performances? How do you keep from stealing even within the domain?

Thanks for this, Kristin. It’s really interesting and thought-provoking to see the course concepts applied to contemporary performance (stage) arts. It enriches the conversation a great deal…