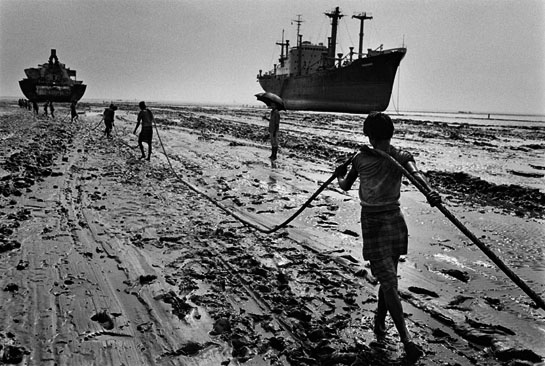

Toward the end of their essay, Tuters and Varnelis write in response to Marxist and Freudian approaches, that it might be “worthwhile to revisit our standard theoretical frames for interpreting technological fetishism” (2006:362). I find it interesting that they seem to be unaware of their own technological fetishism, particularly in citing the MILK and “How Stuff is Made” projects that “geotag” objects rather than people. I’m thinking here of Appadurai and Kopytoff’s The Social Life of Things (1986), and much of the written, photographic and filmic work that has been done on the circulation and political implications of commodity flows, although not as holistically as I guess “spimes” entail. Not to say that MILK and other work that uses locative technologies to “allow one to more fully understand how products are commodified and distributed through the actions of global trade, thereby making visible the networked society” (2006:362), but there are many media that can and have accomplished this. I’m thinking of Sabastiao Salgado’s work (admittedly, human-centric) where he looked at global processes of production through documentary photography in the 80s and 90s (he was originally trained as an economist):

http://www.amazonasimages.com/travaux-main-homme?PHPSESSID=2deb9d0c29aa868ab2a6ff493dfbd308

In Portfolio 6, his images of ship launching in Poland and ship breaking in Bangladesh are poignant here (this is only a partial series of his photo essays). Granted one would have to go to a library and take out the book, whereas I’ve just sent you a link, but I think the photographs do similar things to a project like “How Stuff is Made” and at least when they were made there was no digital technology involved.

In textual works there are lots of examples. Rivoli’s Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy, Henare’s Museums, Anthropology and Imperial Exchange looking at things in networks between New Zealand and Scotland, or Cronan’s Nature’s Metropolis, a commodity-centered historical approach to the emergence of Chicago are a few interesting ones in terms of “tracing” connections. So in response to PDQs on thing-centric locative media practice—thing-centric practice, definitely! Need it be via digital technologies?

There are a number of authors, including Cronan or people like David Harvey, who argue that the more complex networks get, and therefore the more commodities move through interconnected systems, the more the ease of those movements actually obscure the networks and systems of production that make them possible. I’m not sure that locative technologies go very far toward exposing how the technologies that make accessing them possible (iphones, for instance) are connected in these networks. Yes, I think there is “still room to push locative media practices to reveal our own complicity and enfolded experiences of processes and systems of power”!

I also wonder whether what Guy Debord argued for, “intervening in the city with only minor modifications” (2006:359) is accomplished for more people in (“annotative”?) installation works than through locative media technologies. This image of the Gates in Central Park I went to as an undergrad in February of 2005 is one example, and it also reminds me of that image from the Crowd Compiler!

As per your PDQs about direct experience and Hight’s text: What I liked about the Gates was the ways constructions of metal and vinyl in construction-site-orange drew attention to the way Central Park, often imagined as somewhat “natural”, was likewise wholly constructed. Perhaps opposite to the drive to connect local communities to the “naturalness” of sound in Giaccardi’s article, which encouraged “an engaged way of listening to the natural environment and to support a situated and narrative mode of interpreting natural quiet that may foster community building and contribute to environmental culture and sustainable development” (115), the Gates drew crowds to connect to each other in public and clearly constructed city spaces. The day I went there was fresh snow, and my friends and I got into a snowball fight with a bunch of strangers . . . did they subvert “dying everyday practices”? Well I certainly don’t think those are dying practices but the Gates encouraged people to come to Central Park for three weeks the middle of February and stroll, or play, or run around, or talk about installation art . . . to be out in space doing/experiencing something.

I love your post. One comment. The photographs of the Gates are not a direct experience of that space but they are very visually powerful (did you take those or did you get them from an archive).

It’s like Land Art. The documented images of land art are often quite powerful but they are indeed a different experience than being in the space.

One more thing for me to muse on for the next weeks/months to come…