April 10th Symposium: New Media and the Museum––Illuminating Vancouver’s Neon Heritage

For my museum performance in Second Life, my avatar has been composed entirely out of neon signs. These pics illustrate the signs with animations advertising the Museum of Vancouver’s “UGLY VANCOUVER NEON VANCOUVER” show and the IAT 888 class…

The neon words on the custom signs get scrambled before spelling out the full words…UPDATE: This avatar now has the Pepsi head aligned with the Coors Lite bikini body…I have taken some video footage and hope to upload them to youtube, with the Prof’s permission 🙂 I plan to perform at Gallery Xue’s various museum franchises within Second Life and may also set up an installation there (time permitting)…

Hi Class,

I noticed after reviewing my interview with Dennis Moser that I did not mention to him that I had co-produced one of the first documentaries about an avatar community.

The virtual world we explored was Steve DiPaola’s “Digitalspace Traveler”.

Our documentary was from 2003 and was called AVATARA…

Here are some links (including the entire movie online)…

1. Our official website (includes the full feature movie online).

2. A review by Christiane Paul (Whitney Curator).

3. A review by ethnographer, Max Forte.

This seems to me an improvement on the Silence of the Lands program…this is for you Tyler…

Toward the end of their essay, Tuters and Varnelis write in response to Marxist and Freudian approaches, that it might be “worthwhile to revisit our standard theoretical frames for interpreting technological fetishism” (2006:362). I find it interesting that they seem to be unaware of their own technological fetishism, particularly in citing the MILK and “How Stuff is Made” projects that “geotag” objects rather than people. I’m thinking here of Appadurai and Kopytoff’s The Social Life of Things (1986), and much of the written, photographic and filmic work that has been done on the circulation and political implications of commodity flows, although not as holistically as I guess “spimes” entail. Not to say that MILK and other work that uses locative technologies to “allow one to more fully understand how products are commodified and distributed through the actions of global trade, thereby making visible the networked society” (2006:362), but there are many media that can and have accomplished this. I’m thinking of Sabastiao Salgado’s work (admittedly, human-centric) where he looked at global processes of production through documentary photography in the 80s and 90s (he was originally trained as an economist):

http://www.amazonasimages.com/travaux-main-homme?PHPSESSID=2deb9d0c29aa868ab2a6ff493dfbd308

In Portfolio 6, his images of ship launching in Poland and ship breaking in Bangladesh are poignant here (this is only a partial series of his photo essays). Granted one would have to go to a library and take out the book, whereas I’ve just sent you a link, but I think the photographs do similar things to a project like “How Stuff is Made” and at least when they were made there was no digital technology involved.

In textual works there are lots of examples. Rivoli’s Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy, Henare’s Museums, Anthropology and Imperial Exchange looking at things in networks between New Zealand and Scotland, or Cronan’s Nature’s Metropolis, a commodity-centered historical approach to the emergence of Chicago are a few interesting ones in terms of “tracing” connections. So in response to PDQs on thing-centric locative media practice—thing-centric practice, definitely! Need it be via digital technologies?

There are a number of authors, including Cronan or people like David Harvey, who argue that the more complex networks get, and therefore the more commodities move through interconnected systems, the more the ease of those movements actually obscure the networks and systems of production that make them possible. I’m not sure that locative technologies go very far toward exposing how the technologies that make accessing them possible (iphones, for instance) are connected in these networks. Yes, I think there is “still room to push locative media practices to reveal our own complicity and enfolded experiences of processes and systems of power”!

I also wonder whether what Guy Debord argued for, “intervening in the city with only minor modifications” (2006:359) is accomplished for more people in (“annotative”?) installation works than through locative media technologies. This image of the Gates in Central Park I went to as an undergrad in February of 2005 is one example, and it also reminds me of that image from the Crowd Compiler!

As per your PDQs about direct experience and Hight’s text: What I liked about the Gates was the ways constructions of metal and vinyl in construction-site-orange drew attention to the way Central Park, often imagined as somewhat “natural”, was likewise wholly constructed. Perhaps opposite to the drive to connect local communities to the “naturalness” of sound in Giaccardi’s article, which encouraged “an engaged way of listening to the natural environment and to support a situated and narrative mode of interpreting natural quiet that may foster community building and contribute to environmental culture and sustainable development” (115), the Gates drew crowds to connect to each other in public and clearly constructed city spaces. The day I went there was fresh snow, and my friends and I got into a snowball fight with a bunch of strangers . . . did they subvert “dying everyday practices”? Well I certainly don’t think those are dying practices but the Gates encouraged people to come to Central Park for three weeks the middle of February and stroll, or play, or run around, or talk about installation art . . . to be out in space doing/experiencing something.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=UbDYdjhnfEg#!

Fascinated by this . . .

Second Front - "The Last Supper" (2007)- A performance-art group in Second Life. My avatar is located in the middle of the table (pink hair)....

This post deals with Reading Week’s assigned readings which include:

Andrea Bandelli. Virtual Spaces and Museums. Originally in Journal of Museum Education, Vol. 24, 1999. p. 20.

Muller, Klaus. Museums and Virtuality. Ch. 29. Originally in Curator. Vol. 45, no. 1, 2002, pp. 21-33.

Neil Silberman. Chasing the Unicorn? The Quest for “Essence” in Digital Heritage. New Heritage Ch. 6. pp. 81-91.

The recurring theme throughout these readings is that virtuality is more of a museal sequence of experiential “encounters” (Muller 2002:296-297) that can be an acceptable surrogate for the (lack of) available “real” museum artifacts. Since these artifacts are rarely really on display or available to the public anyway (as Muller notes in his Last Supper excursion in MIlan) (Muller 2002:295) and that scholars usually only have access to printed reproductions of artifacts (Bandelli 1999:140-150), the aura has already been sufficient virtualized to become a “real” museum experience. Muller voices the general public frustration that museums often do not have the sought after artifact on display after advertising it (Muller 2002:295) – as most have gone into databases anyway. None of these writers feel that this virtualization is a bad thing, per se. Since museums hardly show the original artifact due to physical safety reasons, the virtual surrogate is really all one has to refer to. It just means that Walt Benjamin was right in forcing the visitor to re-evaluate the relative authenticity of the “original” since we only really have access to the reproduction which may as well be just as real or even more real experientially then original (Muller 2002:298). I am surprised that none of these authors mentioned Baudrillard’s hyper-real notions of simulacra being more real than real. The concept of the simulacra is clearly what all of these authors are tacitly referring to. What I like is how Muller and others acknowledge that the digitization process that most museums engage in is more than a mere reproduction technique (Muller 2002:296). Muller seems to support Levy’s concept of the virtual as being a new synthetic reality rather than as a secondary one subordinate to the “authenticity” of the “real”.

Interestingly, many see museums as a very “real” (rather than synthetically real) civic and sacred space (Muller 2002:297) and so, the museum site in principle, has power as a physical presence. As a result, the museum seems to be the final resting place for the “authentic” (Ibid.). The reason that museums were “trusted cultural institutions” had to do with the myth that the artifacts were “material witnesses” (Ibid). And yet, over the decades, there has been a historical transition from museums being material repositories to becoming immersive story-telling environments (Ibid.). I recall as a kid in the 1970s and 1980s that the Royal BC Museum was a fantastical story-telling space and the authenticity of the reproductions (such as in the 19th century “old-town”) seemed just as pedagogically potent – if not more so – than merely showing the genuine article in a hermetically sealed glass case. The pleasure of visiting this museum was more than social or a desire to connect with authenticity, it was to be immersed as an agent in a world that represented the past – independent of technological novelty (except for the “Water Wheel” exhibit) (Bandelli 1999:148). To experience the essence of the authentic past “[…] on reflection, seems a chimerical goal” as it always “eludes our grasp by changing its form” (Silberman in Kalay et al 2008:83) and so because of this, I place little value in a true connection with the past when going to a museum. It did not even matter that I had access to the museum’s own direct institutional resources and the benefit of such access (Bandelli 1999:149) would not matter to me in a cyberspace version of the museum either unless I had direct ambitions as a curator. These spaces are inherently virtual spaces – at least the more successful ones are. In my opinion and based on my close encounters with the synthetically authentic at the Royal BC Museum, the Disneyfication of museums in general is not an intrusion of museum culture (Muller 2002:303), it helps define the museum as a social space that is equivalent to the narrative and social affordances of pure cyberspace virtual environments (Bandelli 1999:150).

I would like to wrap up this blog post by quickly mentioning how Bandelli believes that the social aspects of a museum experience is thwarted through the virtualization of audio-tours etc (Bendelli 1999:150). I agree with him as I think one needs to explore an immersive world seamlessly as a free-agent in order to enhance the willing suspension of disbelief (Coleridge 1817). Perhaps when intelligent agents truly become interactive guides and address a net-worked chat channel either with a headset or with ambient spatially-distributed speaker configurations with other participants via augmented overlays (holograms?), will the museum’s virtuality become more social in nature.

This is really interesting in terms of discourses about “our children” in a post-Nuclear world:

watch?v=dDTBnsqxZ3k&feature=fvwrel

The “Daisy” TV ad that Johnson ran against Goldwater in the 1964 US presidential campaign, cited as the first televised political attack ad.

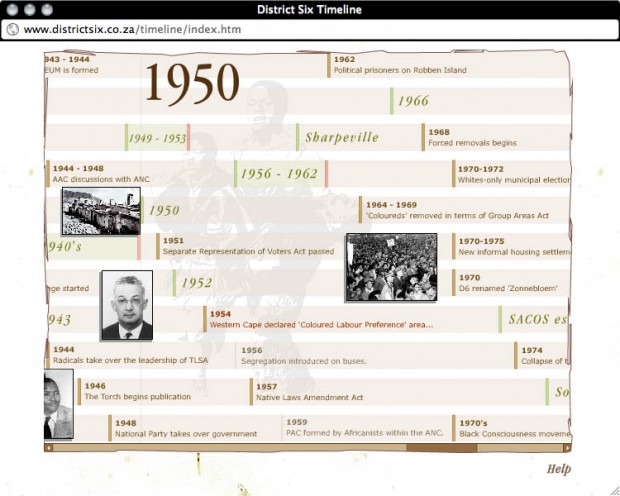

Abungu (2010) paints a picture of the contemporary museums in post-colonial Africa as working to move away from “the old style of exhibition (eg. Dusty objects hidden in glass cases)” (181), and to address the changing face of African society that museums now represent. Part of decolonization, she argues, is a move away from a western museum model, and the positioning of the museum as a tool for social and cultural development. Capetown’s District Six Museum, for example, represents a shift from a focus on objects to the memorialization of the atrocities committed under apartheid––a move from exhibiting tangible heritage to featuring, promoting, and actively documenting and communicating intangible heritage in digital form. Digital cultural heritage from her perspective has the potential to be an agent in the social and cultural work of the museum, telling stories formerly denied heritage value by an oppressive regime, breaking down walls of institutions and creating access for the marginalized; at the same time, its reach is limited by aging telecommunications infrastructure, lack of access to Internet and computers, and conditions of poverty. Abungu’s article points to the role of new media in facilitating access to digital cultural heritage (see Christen’s 2009 piece, and my piece (2009) assigned for this week as well) and the challenges of access outside of urban centres.

Abungu (2010) paints a picture of the contemporary museums in post-colonial Africa as working to move away from “the old style of exhibition (eg. Dusty objects hidden in glass cases)” (181), and to address the changing face of African society that museums now represent. Part of decolonization, she argues, is a move away from a western museum model, and the positioning of the museum as a tool for social and cultural development. Capetown’s District Six Museum, for example, represents a shift from a focus on objects to the memorialization of the atrocities committed under apartheid––a move from exhibiting tangible heritage to featuring, promoting, and actively documenting and communicating intangible heritage in digital form. Digital cultural heritage from her perspective has the potential to be an agent in the social and cultural work of the museum, telling stories formerly denied heritage value by an oppressive regime, breaking down walls of institutions and creating access for the marginalized; at the same time, its reach is limited by aging telecommunications infrastructure, lack of access to Internet and computers, and conditions of poverty. Abungu’s article points to the role of new media in facilitating access to digital cultural heritage (see Christen’s 2009 piece, and my piece (2009) assigned for this week as well) and the challenges of access outside of urban centres.

Abungu’s analysis of the museum in post-colonial Africa speaks to Fiona Cameron’s assertion that heritage discourse––which has come to include digital heritage––is culturally and politically produced. She argues:

“Choices as to what to keep and criteria in which to define objects are made at the expense of others and as Hall (2005) suggests is one of the ways a nation slowly constructs a collective memory of itself. Clearly the same is true for digital heritage items. The value of the past for the future and the nation hinges on these essentialized meanings” (Cameron 2008:177).

Reminding me of Jeremy’s post last week, Cameron argues that Western societies have been largely object centered, “where notions of heritage place the accumulation of objects of critical importance is the transmission of cultural traditions” (Cameron 2008:178). She contrasts this object-orientation with societies that are concept centered, in which objects are preserved because of their ongoing functionality, and in which cultural is transmitted orally––what is now known and codified by UNESCO as the intangible cultural heritage. As tangible and intangible heritage are being digitized in the name of preservation, they are rapidly being inducted in a process of “heritigization”, which Cameron sees as reinforcing Western paradigms of historical materiality (think Walter Benjamin). This process of heritigization is further steeped in the discourse of loss, in which digital heritage is valued if it is perceived as being lost to posterity, rather than for its value in the present. What are the consequences? Should heritage preservation be about more than the archiving of a record, of documentation, of an object? What is the role of the digital object in heritage preservation, and in keeping intangible cultural heritage alive and reproducing? How do we understand the digital surrogate in relation to the original?

Alonzo Addison (2008) reflects on the need to safeguard heritage’s endangered digital record through the lens of built-heritage documentation. By his definition, virtual heritage is practice oriented: “the use of digital technologies to record, model, visualize, and communicate cultural and natural heritage” (2008:27). This work is producing digital heritage, which itself is threatened by changing technologies, data storage challenges, and a lack of interdisciplinary collaboration and cooperation. Addison’s work, scanning and digitally documenting endangered world heritage sites, is grounded in discourse promoted by the UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, which “formalizes the concept of places of ‘outstanding universal value’ to all humankind and proceeds to encourage their protection and preservation for all” (2008:30). (Note that intangible cultural heritage was only formalized as a heritage concept in 2003). As you can see in this message from the Irine Bokova, the Director General of UNESCO, on the 40th Anniversary of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, the discourse of universal value is alive and well (but of course depends on ongoing international support. Lack of support makes even more visible the ideological underpinnings of world heritage policy…). World Heritage, according to UNESCO, “is a building block for peace and sustainable development. It is a source of identity and dignity for local communities, a wellspring of knowledge and strength to be shared. In 2012, as we celebrate the 40th Anniversary of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, this message is more relevant than ever.”

Addison’s chapter is well illustrated in this recent TED talk by Ben Kacyra (below), who has developed technologies for extremely fast, high resolution 3D scans of heritage spaces, and is currently building a global network with the goal of scanning and documenting all of the world’s endangered heritage. He reiterates that the loss of world heritage––heritage that essentially belongs to us all as humans on earth––is a loss of the stories (the intangible) that these places represent, and a loss of the collective memory that tells us who “we” are. Without our heritage, he asks, how will we know who we are?

I am interested in one particular moment in the talk, when he describes how the scanning and digital modeling of a ritual structure in Uganda was put to use after the original structure burned down. In this case, I see potential for intangible cultural heritage–the knowledge of how to build a traditional form of architecture––to actually be revived with the use of digital documentation. Because of the 3D model, the structure could be rebuilt, and in the course of doing this, new knowledge was generated, and potentially passed on. So, what is the relationship of the digital file to the original? In this case, the digital file could be used to recreate the original, but most of the scans by CyArk will simply be archived. What will be documented along with them? Are they removed completely from their contexts of production—do they maintain a connection to the original or do they take on new heritage significance on their own?

Finally, Last week we discussed the news that the US Library of Congress will begin to archive all tweets being generated through the platform Twitter. The response to this announcement is interesting, coming from those who are eager to be able to search the archive, to those who feel that their privacy has been invaded (I never signed up to be archived by the Library of Congress!), to those who think that archiving more than 50 million tweets every day is a colossal waste of financial and human resources. The New York Times discusses a new kind of researcher—the twitterologist––and indeed, the data is tremendously useful for researchers of all kinds, but is it heritage? Why or why not?

Lyman and Besser (2010) discuss the Internet Archive as representing another example of the desire to preserve and archive as much of the emerging digital heritage as possible, before it is “lost”. Through the Wayback Machine, over 150 billion web pages are available, reminding users of the dynamic and contingent nature of the Internet—it is always changing, or more accurately, we are always changing it. Is it heritage?

What heritage should be saved? Who should save it? Does documentation of heritage amount to preservation, to ‘safeguarding’? How is local heritage translated into heritage of “universal value”, and what are the implications? What of the question of cultural property, of intellectual property rights, and copyright in this mess? I like Larry Lessig’s TED talk, in this regard, for the way it spells out some of the legal and cultural foundations of current IP and copyright law. But, to connect a thread back to some of our earlier conversations, what are the some of the ethical issues related to digitizing and making formerly analogue heritage digital—should digitized cultural documentation automatically be inscribed as heritage of universal value, that should be open for access by all… or can we come up with alternatives that contest this emerging norm?

There is clearly a lot to discuss in the seminar this week, from digital cultural heritage as access, as documentation, as ethical and legal touchstone, as cultural policy, as memory and identity, to its representation of shifts in relations of power… I look forward to your thoughts on this post or any of the readings for this week.

References Cited:

Abungu, Lorna (2010). Access to Digital Heritage in Africa: Bridging the Digital Divide. In Museums in a Digital Age. R. Parry, ed. Pp. 181-185. London and New York: Routledge.

Addison, Alonzo (2008). The Vanishing Virtual: Safeguarding Heritage’s Endangered Digital Record In New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage. Y.E. Kalay, T. Kvan, and J. Affleck, eds. Pp. 27-39. London and New York: Routledge.

Cameron, Fiona (2008). The Politics of Heritage Authorship: The Case of Digital Heritage Collections. In New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage. Y.E. Kalay, T. Kvan, and J. Affleck, eds. Pp. 170-184. London and New York: Routledge.

Christen, Kimberly (2009). Access and Accountability: The Ecology of Information Sharing in the Digital Age. Anthropology News (April):4-5.

Hennessy, Kate (2009). Virtual Repatriation and Digital Cultural Heritage: The Ethics of Managing Online Collections. Anthropology News (April):5-6.

Lyman, Peter, and Howard Besser (2010). Defining the Problem of Our Vanishing Memory: Background, Current Status, Models for Resolution. In Museums in a Digital Age. R. Parry, ed. Pp. 336-343. London and New York: Routledge.

Greetings all, here are some additional details about the response paper, due next week. These are a summary of the discussion in our last seminar.