This seems to me an improvement on the Silence of the Lands program…this is for you Tyler…

Standard

March 13, 2012 by kateThinking about “The Visible City” – Looking at other apps

Hi everyone, I am looking forward to discussing the MOV’s “The Visible City” mobile app prototype with you today. I wanted to remind you to take a look at some other recent Canadian apps highlighted by CHIN (Canadian Heritage Information Network) here; while apps from the AGO, the McCord Museum in Montreal, and the Canadian Museum of Civilization represent different approches, content, and curatorial intents, they may also offer helpful points of contrast when thinking about ways that the MOV’s app could be improved in advance of its launch. I have downloaded them to my phone, and maybe we’ll have a chance to talk about them today.

Hi everyone, I am looking forward to discussing the MOV’s “The Visible City” mobile app prototype with you today. I wanted to remind you to take a look at some other recent Canadian apps highlighted by CHIN (Canadian Heritage Information Network) here; while apps from the AGO, the McCord Museum in Montreal, and the Canadian Museum of Civilization represent different approches, content, and curatorial intents, they may also offer helpful points of contrast when thinking about ways that the MOV’s app could be improved in advance of its launch. I have downloaded them to my phone, and maybe we’ll have a chance to talk about them today.

Standard

March 5, 2012 by dianaIn Defense of Non-Locative Media!

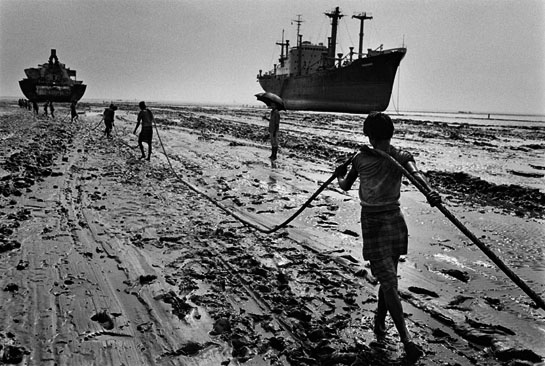

Toward the end of their essay, Tuters and Varnelis write in response to Marxist and Freudian approaches, that it might be “worthwhile to revisit our standard theoretical frames for interpreting technological fetishism” (2006:362). I find it interesting that they seem to be unaware of their own technological fetishism, particularly in citing the MILK and “How Stuff is Made” projects that “geotag” objects rather than people. I’m thinking here of Appadurai and Kopytoff’s The Social Life of Things (1986), and much of the written, photographic and filmic work that has been done on the circulation and political implications of commodity flows, although not as holistically as I guess “spimes” entail. Not to say that MILK and other work that uses locative technologies to “allow one to more fully understand how products are commodified and distributed through the actions of global trade, thereby making visible the networked society” (2006:362), but there are many media that can and have accomplished this. I’m thinking of Sabastiao Salgado’s work (admittedly, human-centric) where he looked at global processes of production through documentary photography in the 80s and 90s (he was originally trained as an economist):

http://www.amazonasimages.com/travaux-main-homme?PHPSESSID=2deb9d0c29aa868ab2a6ff493dfbd308

In Portfolio 6, his images of ship launching in Poland and ship breaking in Bangladesh are poignant here (this is only a partial series of his photo essays). Granted one would have to go to a library and take out the book, whereas I’ve just sent you a link, but I think the photographs do similar things to a project like “How Stuff is Made” and at least when they were made there was no digital technology involved.

In textual works there are lots of examples. Rivoli’s Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy, Henare’s Museums, Anthropology and Imperial Exchange looking at things in networks between New Zealand and Scotland, or Cronan’s Nature’s Metropolis, a commodity-centered historical approach to the emergence of Chicago are a few interesting ones in terms of “tracing” connections. So in response to PDQs on thing-centric locative media practice—thing-centric practice, definitely! Need it be via digital technologies?

There are a number of authors, including Cronan or people like David Harvey, who argue that the more complex networks get, and therefore the more commodities move through interconnected systems, the more the ease of those movements actually obscure the networks and systems of production that make them possible. I’m not sure that locative technologies go very far toward exposing how the technologies that make accessing them possible (iphones, for instance) are connected in these networks. Yes, I think there is “still room to push locative media practices to reveal our own complicity and enfolded experiences of processes and systems of power”!

I also wonder whether what Guy Debord argued for, “intervening in the city with only minor modifications” (2006:359) is accomplished for more people in (“annotative”?) installation works than through locative media technologies. This image of the Gates in Central Park I went to as an undergrad in February of 2005 is one example, and it also reminds me of that image from the Crowd Compiler!

As per your PDQs about direct experience and Hight’s text: What I liked about the Gates was the ways constructions of metal and vinyl in construction-site-orange drew attention to the way Central Park, often imagined as somewhat “natural”, was likewise wholly constructed. Perhaps opposite to the drive to connect local communities to the “naturalness” of sound in Giaccardi’s article, which encouraged “an engaged way of listening to the natural environment and to support a situated and narrative mode of interpreting natural quiet that may foster community building and contribute to environmental culture and sustainable development” (115), the Gates drew crowds to connect to each other in public and clearly constructed city spaces. The day I went there was fresh snow, and my friends and I got into a snowball fight with a bunch of strangers . . . did they subvert “dying everyday practices”? Well I certainly don’t think those are dying practices but the Gates encouraged people to come to Central Park for three weeks the middle of February and stroll, or play, or run around, or talk about installation art . . . to be out in space doing/experiencing something.

Standard

March 5, 2012 by jeremyScaling New “Hights” – Semi-Casual Ramblings about Jer Sr.

Before, I start mentioning some aspects of Jeremy Sr.’s paper, please check out my official interview with him from last year.

I am also hoping to bring him to SIAT to lecture about Locative Media one day or curate a show of Vancouver-based Locative Media artists…any suggestions for museums or galleries with funding that might interested? Also in the summer, I just had an idea to ask him to collaborate with me on a tiny locative Augmented Reality project using the Aurasma app (he did not know about this until probably now – as in, the time he read this blog post).

Anyway, I am going to let Tyler go into detail about Jer Sr.’s work…I have just read his blog now and I look forward to discussing his questioning more in class. I am guessing that Tyler will also go into detail in class about the pioneering “34 North 118 West” (2002) project (3-5), the “Carrizo Parkfield Diaries” (2005, 6-7) and how the “end-user in locative narrative is the movement and patterns of the person navigating the space.” (Ibid:3). This is an opportunity to remind myself to ask a question in the seminar about ways in which geo-located end-users themselves can function AS nostalgic “patterns” of identity (based on Ibid:4,8). I am thinking about how one’s “aesthetic bias” (i.e. personal preferences for navigation and attention) (Ibid) can be mapped archetypally -or perhaps even more idiosyncratically – as both the augmented site-pattern under scrutiny and the avatar-pattern. Such patterns, therefore, can be merged into a symbiotic gestalt.

In the meantime, here are some more casual (i.e. bloggable) impressions from reading his paper…

Although we correspond all the time on Facebook chat and feel as if we have known each other for a long time; from my perspective this Jeremy is from an alternative universe. Jer Sr. is almost like an “imaginary friend” without an authenticated geo-location tag except what Facebook provides me.

He talks about the power of historical overlays where through mediated GPS-enabled devices we can view the history of previous places as if they actually existed (Ibid). This idea of recording historical traces from the same simul-locative site reminds me of Zbigniew Rybczynski’s “Tango” (1981) – a fictional film where pre-recorded segments from within the same space provide multi-linear plot-augmentation through the placement of overlays.

Jer Sr.’s mention of how listening to a blues recording can act as a soundtrack that connects one nostalgically to the exact geo-locative place where it was once recorded (Ibid:1) reminds me of the fact that while writing this blog entry, I am listening to Brian Eno’s classic “Music for Films” (1975-78) album on vinyl.

Inspired by Erik Satie and John Cage, Eno saw these hypothetical soundtracks as “imaginary landscapes”.

Eno also uses aesthetic augmentation to provide a soundtrack for imagined geo-locative landscapes and/or films etc. However, no affordable geo-locative tech was enabled during Eno’s time. Eno’s ambient music induces nostalgia for places that may or may not exist in empirical reality,

In either case, one can use all sorts of media to activate narrative associations (based on Hight 2006:2) with a real, virtual or imaginary landscape.

The main difference between Hight’s locative media projects and Eno’s music is that Hight is using empirical (i.e. scientific and historical data, 2-3) phenomena to validate the authenticity of particular cites for the purpose of “narrative archaeology” (2, 5-6). In Eno’s case, there is no particular site in mind as the music is merely meant to bring the geo-evocative landscape to life only in the listener’s imagination.

In both cases, Hight and Eno seem interested in the dialectic of Site/Non-Site that was prevalent in the “Land Art” (2) or “Earthworks” of Robert Smithson and Robert Morris II (Robert Morris I was a similar artist and architect working in England in the 18th century). In the 1960s, site/non-site works served as historical and scientific augmentations not just for a neutral white-cube gallery space (non-site) but also for the original landscape from whence the aesthetic speculations first occurred.

More so than even Eno though, Hight would like to see the gallery and museum methodology of historical contextualization move beyond the gallery space and into the natural and built environment outside – contextualized as culturally valid Contemporary Art.

…Ok, that is all for now..I will prepare my comments from at least one other reading and look forward to Tyler’s discussion on Tuesday.

Standard

March 4, 2012 by tylerWeek 9: Locative Media

Hello everyone! I look forward to reading and hearing your responses to this week’s readings, all summarized in one fashion or another below. I thought it might be good to just outline a few trends that I picked up on in the readings, just to prime you for conversation on Tuesday. I am slightly bothered by the readings of locative media from this week, though I enjoyed most of them. I notice a trend to discuss the great potential locative media has to deepen our experience of place in new ways, and yet, rarely are there accompanying descriptions of place or space.

(I will distinguish this a bit more on Tuesday, but I consider space to be the physical organization of things in space, where place is something which carries with it a sense of identity, or possibly even emotion—so “home” has a physical reality, but also undertones of cultural and personal associations.)

The authors all make note of place, they ensure us that many of these projects actually engender new experiences of place, but they do so primarily through social and historical means—that is making evident social or historical connections that one may not be aware of. And that is great! (Really, no sarcasm.) However, I cannot shake the feeling that there is a lack of attention to the real-time unfolding of experience—the physicality of space—that is being slightly ignored in these arguments, and I think to the detriment of experience. This seems rather vague to me, and I am having difficulty finding a clear way to describe it, or find a really good example of it. So, I will want to talk about that, land art, and technological frameworks of experiences of space/place on Tuesday. Please feel free to suggest détournements and dérives that alter that trajectory in the comments.

I will also make up for the lack of images with many pretty pictures during class. I promise.

Tuters, Marc, and Kazys Varnelis (2006) Beyond Locative Media: Giving Shape to the Internet of Things. Leonardo 39(4):357-363.

Marc Tuters and Kazys Varnelis detail the tensions embedded within locative art, tensions that come out of expectations for artists to be critical of both corporate and ideological frameworks seen. Emerging at the time that net art (arguably) began to wain in popularity, locative media seemed ripe to follow net art practitioner’s critical distance from corporate interests and practices (357). The authors see locative media closely aligned with geohackers, phsychogeographers (Situationist movement) and the free wireless movement—all movements highly critical of commercial interests. Thus, they see within locative media the possibility of “re-embodying” experience in the built environment as a response to capitalist forces of production that are diminishing our experiences of space/place (359). And yet, corporate sponsorship, technologies of surveillance and ideologies of mapping (ie. Cartesian models of understanding the world) all support the practices of locative media.

The authors boil down locative media into two major approaches: annotative and tracing. “Annotative projects…generally seek to change the world by adding data to it…tracing-based projects typically seek to use high technology to stimulate dying everyday practices such as walking or occupying public space” (359). Here, the authors align locative media most strongly with Situationism, where annotating the world with data is analogous to détournement practices, such as “adding a light switch to street lights.” While tracing is analogous to the dérive, or wandering the city. Here, Situationism is argued as “a series of programmatic texts” (359). This is yet another bridge to locative media, which the authors point out is almost exclusively indebted to computer software (and hardware too, of course) (359). This is perhaps the source of the identified tension, for developing software and technology for locative projects requires that practitioners “adopt the model of research and development wholesale, looking for corporate sponsorship or even venture capital” (360).

For example, Blast Theory and Proboscis, two locative media art groups, both accepted corporate sponsorship for different projects—projects which blur the distinction of art and public relations. Anne Galloway, an anthropologist, calls for a more “structured mechanism for accountability, professionalism and ethics” (360). However, while Andreas Broeckmann, director of Transmediale, said that practitioners of locative media “have a duty to address [technologies of surveillance and control] in their work” (ibid). Coco Fusco, a new media artist, goes even further, suggesting that with locative media practice over 40 years of critical theory have dissipated and that artists need to examine the geopolitical forces in which they are situated (360-361).

The authors seem genuinely amused at the simultaneous laudatory and disparaging views of locative media from different angles. They also suggest that neither view of locative media is capturing its full potential. Instead, they argue that we should focus not on the human subject of locative media, but on things. Using Bruce Sterling’s concept of “spimes”—context aware objects that convey “information about where they have been, where they are and where they are going” (362). This would allow for a nonhuman understanding of capitalist forces of production, “an awareness of the genealogy of an object as it is embedded in the matrix of its production” (362).

I really enjoyed the way that this article draws out the rich tensions across different ways of knowing space and place, the call for politically aware art, and the different ways that artists negotiate systems of capital. It’s a lovely, tangled knot of our contemporary world that goes beyond art into how each of us chooses to live in such a world. I also enjoyed the reference to nonhumans (down with anthropocentrism!), and yet, I was surprised by their sudden shift to the nonhuman. I am all for more nonhuman views of the world, but I am skeptical that spimes are necessarily going to describe more clearly the material processes of capitalist forces and the effects therein—at least not without a shift in human experience of such processes.

PDQs:

Do you agree with the shift to a thing-centric locative media practice? Can that make for an opening up of productive forces to understand, critique and change them? Do you see spimes shaping our experience of space? How so? Is there still room to push locative media practices to reveal our own complicity and enfolded experiences of processes and systems of power, before jumping to to things? Are walking and occupying space truly “dying everyday practices”?

Hight, J. (2006). Views From Above: Locative Narrative and the Landscape. Leonardo Electronic Almanac, 14(7/8), 1-9

Jeremy Hight details his artistic practice and the potential of embedding narrative elements into the landscape via locative media. In this way, he argues that the viewer/participant is able to experience a much richer form of place. “The cities and the landscape as a whole can now be navigated through layers of information and narrative of what is occurring and has occurred. Narrative, history, and scientific data are a fused landscape, not a digital augmentation, but a multi-layered, deep and malleable resonance of place” (1).

Hight describes his entry into locative media as an attempt to deal with narrative of place. Beginning with experiments of overlaying text on physical locations, new technologies allowed for a more fully realized integration of narrative and place. “Narrative could be composed not of elected details to establish tone and sense of place, but could be of actually physical places, objects and buildings. It was as though the typewriter or computer keyboard had fused with fields, walls streetlights; the tool set was suddenly of both the textual world and the physical world” (3). Hight explains that the technology allowed for a new kind of “reading” of a place, an affordance that reveals hidden experiences drawn from the historical record of a place. Narratively, this unfolds not just through the triggers of information—where and how information is delivered through the technological infrastructures—but also how the narrative elements are selected “in relation to the properties of each location” (3).

34 North 118 West is a project Hight worked on with Jeff Knowlton and Naomi Spellman. A series of locations were tied to narrative segments. Participants were able to generate the narrative sequence by using an interactive map to guide them from one location to the next in whatever order they wanted, listening to the narrative via headphones. The narratives were pulled from the history of the site, thus participants were able to experience something out of the past in the present. Another project, Carrizo Parkfield Diaries used seismic data to generate the sequencing of narrative elements, thus the earth itself constructed the narrative sequence—if not the narrative elements. Hight calls this “Narrative Archaeology,” focused on revealing the historical changes of a site to the audience through a range of data. Historical, social, and scientific data can all be woven into the fabric of locative narrative. This integration of narrative and media into the landscape so that it may be “read” is only at the beginning stages, according to Hight. “The future of locative media lies in applications of ever-increasing variation fed by many kinds of data and generating narrative of any area where strutters may be read—the city, the subterranean, and the wild itself” (9).

I come away from this article with the sense that the attention Hight places on space pales in comparison to the narratives that he creates. What I mean by this, is that while we get glimpses of the narrative, there are few descriptions of the physical space that the narratives occur in. That is to say, there are no compelling points in the article that show how the physicality of place, or space, influence the narrative. I found this subtle lack of attention to space a running theme throughout many of the artistic projects described. Unfortunately, I cannot explain this more clearly (maybe by Tuesday I will have it down!), however I am curious if anyone else gets a similar vibe from this, or other articles.

PDQs:

Hight offers a new form of reading place through narratives derived from and organized by a range of data. However, there seems to be a lack of emphasis on the present experience of place. Does a historical archaeology of space allow us a deeper appreciation of what we are experiencing in situ? Or, does it only redirect our attention from what we are currently experiencing? It seems to me that, though interesting and engaging, Hight’s projects are not about reading the place as it is, but revealing the human traumas previously experienced. Thinking through spimes (Beyond Locative Media) offers a nonhuman critique of his, arguably, human-centric treatment of place. What are other ways we can think of space and place outside of narrative?

Rothfarb., R., Mixing Realities to Connect People, Places, and Exhibits Using Mobile Augmented-Reality Applications.

The Exploratorium in San Francisco details some of their work in locative media and AR in this article. The article covers a range of AR technologies including markers, and AR applications, examples of their work with AR, and even some guidance and best practices for other organizations looking to create AR experiences for their audiences. I found it extremely practical, and makes me want to go back to the Exploratorium, which I haven’t visited since I was a kid. Since we went over AR last week, and it appears we have a fairly good grasp of the technology, and in the interest of time (mine and those reading this), I am just going to cover one brief example of this app which is related to locative media. Specifically, I want to suggest that the Golden Gate Bridge Fog Altimeter is one of the few locative media applications focused on deepening the experience of space in real-time through technology. The authors do not go into great detail about the exhibit, writing only, “The exhibit becomes a virtual instrument that visitors can use to measure the altitude of fog in the bay by observation and to learn about weather phenomena that affect fog penetration into different parts of the city – a “take it with you” tool that can be used for personal investigation” (5).

It seems to me that this is a deepening of active experience, one which goes in direct contrast to 34 North 118 West and narrative driven projects. The goal here is to provide understanding of what one experiences. Weather processes may not be noticed, or understood, but they clearly impact our experience of space and place. The fog in San Francisco is part of the lived experience and understanding what is happening in the moment can be just as meaningful as the hidden narratives of those who once inhabited this space. However, it is difficult to tell what, exactly, the experience of this exhibit is, as it is only briefly mentioned. I just wanted to offer it as a counter to some of the larger, art-based projects that, from my point of view, tend to emphasize historical or social experiences than environmental.

Elisa Giaccardi. Cross-media interaction for the virtual museum: Reconnecting to Natural Heritage in Boulder, Colorado

This article describes The Silence of the Lands—a locative media project focusing on the sounds of nature in Boulder, Colorado. Elisa Giaccardi details both the philosophical approach to the app, as well as a description of the supporting technologies. The specific technologies (already slightly outdated, arguably) are not as important as the general technological infrastructure and activities supported, at least in my opinion. Briefly, the project works in the following stages:

1. Participants go into nature with a GPS enabled PDA to record sounds in nature. Giaccardi likens the device to a “sound camera” and the experience to taking snapshots.

2. Sounds are loaded to a web server and participants can go online to catalogue their sounds. It is a process of engaging with the sounds through personal memory and the objective reality of what is recorded.

3. Public sessions invite community members (who may or may not have participated in the capturing of the sounds) to create ideal soundscapes via an interactive table with mapping overlays.

Giaccardi also references the ability to create soundscapes on the website, but she did not include it when describing the above scenario. It seems that her focus is on the communal aspect of the project, and the ways that the project supports a move from the individual to collective experiences. This is definitely still valid for the web based editing, but the emphasis on shared soundscape creation seems important.

The result is collage-like, both in the resulting artifact, as well as the individual and communal actions needed to create the work (recording, cataloguing, and editing/representation). It is a form of shared meaning making, through different levels of collaboration. Giaccardi acknowledges that simply providing the technological infrastructure is not enough to engender such collaboration, and details a series of “social infrastructure” initiatives to get the community involved. Namely by working with local municipalities to encourage participation in organized soundwalks and community workshops. Her goal is to use sound as a way to catalyze and understand the community’s perspective on and relationship to the surrounding natural environment through these technological and social infrastructures:

“The primary objective of this project is to encourage an engaged way of listening to the natural environment and to support a situated and narrative mode of interpreting natural quiet that may foster community building and contribute to environmental culture and sustainable development. What we envision is to connect the Boulder community and its land, and to cultivate their creative relationship by enabling inhabitants and stakeholders to look at each other’s experiences, connect with each other’s perceptions, and inform their actions upon the shared narrative that is unfolding over time” (115).

Giaccardi positions the project as fundamentally different from other virtual museum initiatives, which she claims focus on the archive. Instead, she offers the model of the “repertoire” to describe the intertwining of individual and communal experience and perspectives. Thus the experience of the mobile app is focused on allowing individuals to record and map their experience in nature and to share these recordings as “digital representations” that express “their different values perspectives” (115). By providing collaborative, creative tools (recording and composition), it is hoped that the participants’ artifacts will reveal their understanding of and relationship to the natural evironment. Rather than just being a “digital archive,” she says it is a “repertoire —meant to sustain the whole system of knowledge and reproduction as a living system” (118).” She argues that the difference is predicated on a continual actualization of the community’s relationship to nature, the virtual museum is the site of activity and action that represents an unfolding reality.

I think that this is a very interesting locative media process, one which attempts to capture the experiences in nature and creatively repurpose them. I am skeptical of some of the author’s language. She describes the process of going into nature to record sounds as “authentic, direct and intimate,” but she fails to look at any ideas of technological framing of the project, or the encounter with nature (122). Going out to record sounds, in my personal experience, is different than just going out to walk in the woods. Purpose can change the experience, and arguably create a goal-driven experience. Of course, there is nothing wrong with this! It is just different. However, I find the lack of philosophical attention to technology strange in this article, as it neglects the way technology informs the project, especially since the article itself is so philosophically savvy.

PDQs:

What do you think of this idea, repertoire vs. the archive? Is it a fair characterization of other digital initiatives? Does the strategy reflect a shift in stance, or is it just wrapped up in nice rhetoric? Could Fiona Campbell’s papers on enhancing multiple meanings of objects also be considered a strategy of repertoire? James Clifford’s zones of contacts?

What about the role of technology in this scenario? Giaccomi does not address the way that technology shapes the experience of being in nature, recording and editing sound, or even engender a specific kind of interaction between community members. Are there not systems of logic in place (i.e., the design of the app, editing tools, interaction table) that, like any museum display or other ‘programming’, shape the potential actualizations and conceptual frameworks through which participants make meaning?

From Picassos to Sarcophagi, Guided by Phone Apps (New York Times, Oct. 1 2010)

This review article of a number of museum apps is a great continuation from last week’s AR/VR readings. It focuses on the museum experience while using apps and picks up on Barney’s article (Terminal City). It aligns with his broader critique that looking at one’s phone when standing in front of a piece of art is kind of missing the point. However, and I think more important to the museums and app makers, the author notes how bad the apps are for deepening the museum experience. Rothstein notes that there are a number of useful activities apps can help us with while in museums, but they mostly come down to way-finding techniques (Where is the bathroom? Which room can I find the Mona Lisa in?) or providing more information about a particular work of art.

The way-finding techniques are not yet widely implemented, and can be tricky. The best solutions seem to be museums who have installed wifi routers in the building and can triangulate visitor position that way. This is useful when available to receive information about specific exhibits or amenities. However, even when implemented as in the Museum of Natural History, the delivery of robust, deep content about the museum collection seems widely missing.

Rothstein laments that most of the apps are lacking content, providing only thin descriptions. What is best about this article, I think, is his vision for what these apps may provide in the future. Interestingly, I think it aligns nicely most of our readings thus far in the semester. “It is best to consider all these apps flawed works in progress. So much more should be possible. Imagine standing in front of an object with an app that, sensing your location, is already displaying precisely the right information. It might offer historical background or direct you through links to other works that have some connection to the object. It might provide links to critical commentary. It might become, for each object, an exhibition in itself, ripe with alternate narratives and elaborate associations.”

Townsend, A. (2006). Locative-Media Artists in the Contested-Aware City. Leonardo, 39(4), 345-347.

This article examines location aware technologies in a specific context-aware form, highlighting two distinct approaches of technological implementation: top-down systems and bottom-up systems. The author suggests that these two strategies will result in an ongoing power struggle waged through technological systems deployed in the built environment. Townsend offers a slightly different take on location aware media, moving instead to a “context aware” model enabled by new sensor technology. “These new technologies are characterized by their ability to gather information about their surroundings by sensing the physical world, understanding these data, identifying patterns and acting or reacting” (345).

Townsend states that the complexity of these technologies has engendered top-down and bottom-up strategies of design. Top-down strategies “use relatively simple sensing mechanisms, highly formalized vocabularies for describing and organizing sense data, and closed channels for communicating context” (345). Meanwhile, bottom-up strategies use “more sophisticated sensing mechanisms, very informal data vocabularies and open systems for exchanging context” (345). Top-down strategies are centralized control-driven designs—Townsend uses a toll system as an example. Control is strict and tied into various systems of tight control: identification systems, billing systems, etc. Bottom-up examples are the tagging system of del.icio.us and Flickr, they are often called “folksonomies,” tagging systems with open vocabularies (i.e., users can add new tags at any time).

These two different strategies are beginning to reveal different forms of context awareness, and on some levels clash against one another. For instance, he contrasts the universal presence of visual surveillance (top-down) to the (bottom-up) Open Street Map project that uses GPS logs of amateur surveyors “to create a free set of digital street maps” (347). In many ways, he pits artists and community organizations as bottom-up innovators in resistance to control-oriented top-down systems of governments and corporations. The two different strategies impact on how we experience place. “For the question being raised by context-aware systems are about more than just location, how we experience space and the meaning of place” (347).

There is an overriding technologic deterministic tone to Townsend’s article. One that has already given in to the inevitable integration of technologies and cities. “The artists of tomorrow with [sic] have to explore the meaning of perception in a world in which we will have our sourced many of our perceptive tasks to machines, to extend and augment our abilities” (347). The technological landscape, as he puts it, is determined at odds through the technologies mobilized. However, it is as if there is no room for change. I have a hard time with this view. Cultures change, and the privacy concerns he lists as one of the motivators for bottom-up technologies will undoubtedly shift with generations growing up on line along with technologies like Facebook. The dualistic approach Townsend takes seem likely in the short term, but I wonder how long this contest will really run for.

PDQs

Are these the only design strategies we can come up with for how we enable technological systems to be context aware? If so, must they automatically be contested? Is there no room for hybrid practices of middle-up-and-down systems that enable new vocabularies of experience? Is a context-aware environment really going to force us to offload our perceptive tasks?

Shirvanee, L. (2007). Social viscosities: mapping social performance in public space. Digital Creativity, 18(3), 151-160.

Lily Shirvanee writes about locative media practices that “address a social consciousness” (151). She coins the term “social viscosities” to describe the “dynamic spaces of flow between people that emerge as collective activities begin to form in mobile social groups” (151). Locative media can bring forth unnoticed, and instigate new forms of, collective activities. She covers a range of artworks that attempt to do just that through a few key strategies:

Narratives in time and space—Focuses on project like 34 North 118 West. Here Shrivanee focuses on how social practices inform the production of space, and how narrative can shift the social experience of space. It creates a “resonance” between the participant and “others who have inhabited the same space” (153).

Mapping Social Histories—In Amsterdam RealTime participants were tracked via GPS in an attempt to visualize the traces of real-time activity in the city. “Locative mapping as personal expression can become interesting to individuals as a reflection and as a narration of their experience” (154).

Mobile Gaming Culture—Botfighters allows players to track one another in the city. GPS data allows the proximity of players to be determined and “indicate when another is close enough to tag or hit…In the complexity of the urban context, this game becomes a tool for mediation—a tactical device that not only enables strangers within a locative range to communicate with each other, but also has the potential to create a shared narrative between individuals that may create ripples of familiarity across a society of gamers” (155).

Surveillance and Social Spam—Films like Minority Report and Blade Runner as dystopian visions for advertising run amok. Projects like Personal Telco Project, which were providing free wireless to the public have recently been shut out of the social space by corporate wifi by Starbucks and T-Mobile signals that overpowered the independent, free service where “the potential for a new urban storytelling is surprised by commerce” (157).

These themes are analyzed through Shirvanee’s Social Viscosity project, which seeks to create a “storymapping project that tracks ‘social viscosities’ in Cambridge, UK” (158). Building on the themes above, Shrivanee expects that her project will bring forth community voices in active disruption of “political and commercial control” of public space. Her project, and the ones detailed in the article are all enabled through locative media, and she argues that these projects have the potential to create a connective space through such technologies (159).

Speed, C. (2010). Developing a Sense of Place with Locative Media: An “Underview Effect.” Leonardo, 43(2), 169-174.

Chris Speed works off of the “Overview Effect”—the reported experience of astronauts when seeing the earth from a distance feel an overwhelming sense of connection to the entire planet—to develop his own idea of an “Underview Effect”: using locative and social media to present an altered experience of place that “supports a sense of place” over a sense of time (169). His view is that technologies of navigation and mapping make our connection to place difficult to maintain. The “Underview Effect” is the author’s attempt to reinvigorate a sense of space while being on the planet, which he argues is difficult to maintain due to the Cartesian models of space and time. “[W]ith the development of the map and the marine chronometer that allowed seafarers to navigate places safely, space was split from our sense of time, making it very difficult for any future technology based on thiese systems to convey any actual sense of place—any sense of “here” or “there…Digital systems have proceeded to capitalize upon the use of the split system to an increasingly extreme extent, which at its peak posited the idea of virtual realities; spaces that promised an extreme lack of place and embraced a form of homelessness” (170). This split model of space and time is still prevalent in the map, according to Speed, and locative media needs to “be sensitive in the way that it adopts Cartesian and abstract ways of describing a sense of place” (172). In his own work, Speed and collaborators tried to do jus this when they created Digital Explorations in Architectural Urban Analysis.

They recorded GPS data from 17 people to create a simultaneous mapping of space through the group of people. The time stamp was removed from the GPS data He writes, “This apparent geography is unusual because it is the result of a social process. It is a landscape collected through the movement of groups of people working together to explore a specific place. In many ways, the topology describes knowl- edge of that place because it documents their movement across, around, over and through it. Traditional use of the same data depicted the lines of each of the 17 GPS devices over time and would have required a base map of Dundee for a user to understand the geography” (173). While I find his description of this lacking—I am honestly unable to make sense of how social mapping could be made to work “simultaneously” without reference to the time data—I nonetheless enjoy the goal of his work, a poke at the rational, Cartesian models of understanding space and place through a distributed “body” of multiple individuals.

However, once again, I find here a lack of attention to the experience of space/place as it unfolds. It focuses on processes of analysis after the experience of place.

Kabisch, E. (2010). Mobile after-media: trajectories and points of departure. Digital Creativity, 21(1), 46-54.

Eric Kabisch describes his project Datascape in terms of an after-media practice—”an approach toward media that sets itself in opposition to that which came before it” (47). Pulling from Benedcit Anderson’s idea of imagined communities, Kabisch describes how cities and communities are bound also by “shared visions and stories through witch their constituents identify both personally and collectively” (46). “Datascape is a geographic storytelling platform that enables artists, researchers, community groups and other individuals to narrate their local communities through geographic data” (ibid). He explains that his project began with the goal of exposing the use of consumer and demographic data to develop narrative descriptions of city blocks by marketing companies. Using a modular system of software, Kabisch will work with communities to incorporate technologies to enable communities to create the narratives they want to tell. Some examples of the projects using Datascape are: “graduate education majors who will be using the system to enable ecological and historical education around Newport Bay for high school students; artists and atmospheric scientists who will be using atmospheric data to illustrate correlations between changes on Earth and on Mars as a lens toward the importance of the issue of climate change; researchers who are collecting community information through cell phone users in order to highlight local community issues; a cultural anthropologist who is mapping the social geography of local Native American groups and how it has changed over time; a department of Cultural Affairs preparing interactive and interpretive experiences for visitors and residents; and a youth-artist-mentoring community group that enables disadvantaged youths to tell stories about their local communities” (49). Kabisch’s work is a response to mapping technologies and this informs his practice. He writes, “locative media as an offshoot of the underlying technologies of GIS is quite bound to previous modes of representation. I suggest that the requisite geodata ontology is typically carried through to the level of representation. A place—in all its richness—becomes a static marker on a map, a journey becomes a line, and a community becomes a polygon outline.” (49-50).

Kabisch nicely cycles through the various tensions and critiques inherent to locative media that we have seen in the other papers: an association with commercial interests, not being political enough, reliant on Cartesian models of space, and so on. His view of an after-media practice is interesting in that it works as a way to understand all of these issues. However, he does not explain how these elements manifest themselves in his work, how one practically addresses the deep tensions of an art practice through the ‘materials’ of the medium. So, his article, while interesting, and clearly delineating the critical issues surrounding locative media, does not explain how after-media works as a practice—it appears much more like a theoretical tool.

Standard

February 28, 2012 by jeremyReady for tomorrow’s Virtual and Augmented Reality Seminar…

Hello all,

I have just finished my Powerpoint presentation for tomorrow’s seminar.

If any of you have smartphones or iPads, you may want to download the Layar app to see the projects described in most of the readings.

In the meantime, here is an AR video worth watching…

Standard

February 28, 2012 by dianaHonda’s Augmented “Reality” Commercial

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=UbDYdjhnfEg#!

Fascinated by this . . .

Standard

February 27, 2012 by kateAR: ‘Never Stop Playing’?

I saw this commercial on TV over the weekend and thought that it captured an aspect of Augmented Reality applications that I find troubling. The ad’s protagonist exists in an empty city, only noticing other ‘players’ of the game he is involved in. “Never Stop Playing”, is the tag line–but seeing the ad, and watching this celebration of total isolation from the sociality and relationships that are a part of urban life, I can’t help wishing that people would stop playing immediately and spend more time being aware of their everyday contexts. Am I wrong to be skeptical? While I know that there will be a huge market for games like these, I would love to see the development AR applications that somehow connect people to their everyday spaces, their social and political contexts, or just their neighbors, instead of isolating them even more. For that reason I like the Occupy Wall Street AR app that we discussed earlier in the term, but does a project like this even get close to connecting people to the actual space that they are in? Hopefully we can discuss this a bit in class.

Standard

February 20, 2012 by kateVirtual Museums

Many thanks to Claude for her great synthesis of this week’s readings on virtual museums, and for many excellent questions for discussions. I am looking forward to Tuesday’s class. In the meantime, I wanted to link to a few examples of virtual museums that are worth spending some time looking at and thinking about in relation to the readings from this week (which of course build on the conversations we have been having all term).

Many thanks to Claude for her great synthesis of this week’s readings on virtual museums, and for many excellent questions for discussions. I am looking forward to Tuesday’s class. In the meantime, I wanted to link to a few examples of virtual museums that are worth spending some time looking at and thinking about in relation to the readings from this week (which of course build on the conversations we have been having all term).

What do you think of the Google Art Project? The Virtual Museum of Canada also hosts hundreds of online exhibits. We looked at the Adobe Museum and its exhibits in class, which is intriguing and clearly demonstrating the strength of Adobe software and some virtual curatorial vision. A student recently showed me the Valentino Garvani Virtual Museum, for lovers of fashion (thanks Serge!)… There is the BBC and British Museum’s A History of the World in a Hundred Objects; or MOMA NY’s virtual exhibit produced for their Cartier-Bresson exhibit…. all so different, all playing with the medium and searching for a new way to communicate the collections and mandate of the museum. Have you encountered any sites worth exploring in your online travels and research?

Standard

February 19, 2012 by kristinNeon Signs Made with Bacteria

Image from Hasty Lab, UC San Diego from: http://futureoftech.msnbc.msn.com/_news/2011/12/19/9565060-neon-signs-made-with-bacteria

Tyler – I thought of you while searching for explorations with neon signs. This article describes research from UC San Diego that is exploring the use of fluorescent bacteria as bio-pixels for screens.

http://futureoftech.msnbc.msn.com/_news/2011/12/19/9565060-neon-signs-made-with-bacteria