Standard

February 19, 2012 by claudeWeek #7 seminar / When museums go digital: redefining the space of the exhibit

virtual-exhibits-virtual-museums

In this week’s seminar, I will be starting my presentation by giving a brief overview of some of the different forms and functions that virtual exhibits can take, illustrating these with examples. I will also present the highlights of a paper I wrote last semester on the digital affordances used to curate a virtual exhibit while we navigate through the exhibit online. After this, if we have time, I am hoping we can address some theoretical or ethical issue(s) related to virtual exhibits. I am very open to any of your suggestion(s) about what the class discussion should focus on and I am also open to presenting any virtual or visual material that you would like me to include. You can let me know in advance or else surprise me on the spot.

Before I give a brief summary of this week’s readings, I would like to start this blog post with a quote from a book that is not part of our course readings, but that is of great interest and use to me in my inquiry into the parallels between street art and web art, as well as between public space and virtual space. This book was written by one of my Concordia University art history professors who, for her doctoral research, travelled all around the world to document street art and graffiti, interviewing artists to gain insight on the function(s) of these art movements that have garnered increasing recognition by art world institutions and stakeholders. I am deliberately picking a quote, and a context, that is not directly related to the topic of “new media and the museum” to cast a wider net for our class discussions in the hope that you will consider ideas of space, context, and function that go beyond current new media scholarship.

“The problem with galleries is that 99% of urban artists use urban art as a stepping stone into galleries. It’s a fatal error because in galleries they’re seen by 40 people, in museums they’re seen by 10 people, but in the streets they’re seen by 100,000 people. And that’s the integrity of an artist’s work: to be seen. Not to be sold or to be recognized in a museum – but to be seen by the world.” (Street artist Blek le Rat qtd in Waclawek, 2011, p. 70)

Tate Gallery London 2007 - "Lady Diana and the shadowman", street art stencil by Blek le Rat. Source: WWW : the artist's website

So far our course readings have mostly provided us with a scholarly perspective on art, archives, as well as tangible and intangible cultural heritage in relation to the museum, its institutional discourse, and its relationship(s) to communities of practice that produce cultural artifacts. This seems perfectly reasonable since this is the title, and topic, of our course. However, in discussing virtual exhibits, as an agent provocateur, I felt it was important to draw your attention to two other important players, namely the artists themselves and the curators.

(SR #6) I found Gansallo’s (2010) article most intriguing in this respect in that it addressed the problematic relationship of both these parties to a well-established high-profile contemporary museum. The author discusses the difficulty of curating web-art embedded in a museum’s institutional website (in this case, the Tate website) when 3 different artists are individually commissioned by the museum itself to create web-art that calls into question how art is viewed (p. 346, para. 1). As curator, Gansallo became the go-between that enabled “the artists [to] have the right to present their ideas and their work without any interference whatsoever from people telling them what art is and what they should and shouldn’t do” (p. 348, para. 5).

PDQ : How can dominant culture/high-art institutional infrastructures accommodate and support subversive web-art that challenges the existing power structures institutions legitimize and shape?

(SR #5) In providing readers with an overview of many of the forms in which tangible and intangible cultural heritage is presented today, this article raises important question with regards to the role of digital technologies in preserving this heritage. Quoting Lowenthal (1994), Silberman (2008) urges us to consider the epistemological and discursive nature of cultural heritage, because, he argues, it may tell us more about the present than about the past: “the more realistic a reconstruction of the past seems, the more it is part of the present” (p. 83, para. 2). Alternatively, he suggests that cultural heritage can also be understood as a means to illuminate how the past has brought us into the present. Finally, he adds that our quest for essence in digital heritage may reflect “an overall understanding of why the Past is so important no less than what it is [sic]” (p. 90, para. 2).

In week #5’s readings, Fiona Cameron (2008) discussed this notion of the “essence” of cultural heritage in the following terms:

“A new way of looking at cultural materials in a digital format and as a model for organizing complex information online is to engage Andre Malraux’s idea of the museal, the museum characteristic of citation (quoted in Bournia 2006). Citation rejects the notion of a permanent pattern of human experience around the idea of art, or indeed heritage. In dissociating cultural materials in digital format from a sense of permanence as heritage, as an expression of their enduring essence, and instead reading objects as citation, opens selection and significance to other values and to the creative interaction between social and cultural systems as complexity” (p. 182, para. 3)

PDQ : In what way(s) does digital media problematize the “essence” of cultural heritage?

(RR #4) Comparing the exhibitionary techniques of traditional museums to those of today’s virtual museums, Lewi (2008) describes how the concept of architecture was central to the design of the CD-ROM project titled Visualising the architecture of Federation, a virtual exhibit representing the heritage of Western Australian architecture for Australia’s Centenary of Federation in 2001. She examines how architectural design was the organizing principle used to structure both information and the virtual exhibition space itself, an idea that was conceptually consistent with this project which was intended to celebrate the Western Australian Museum’s “architectural monumentality, its social status as a public space, and as an institution for research and public education” (p. 202, para. 3). Lewi offers a detailed discussion of some of the formal and logistical limitations and problems associated with the creation of a virtual counterpart to the traditional museum, in particular, lamenting the fact that lack of funds has not permitted to make this endeavor accessible on the internet.

PDQ: What is the relationship of virtual architectural exhibits to the real architectural structure(s) they aim to represent (if we reflect on it in terms of pros and cons)?

(RR #1) Tracing some of the origins of the virtual museum, Huhtamo (2002), identifies the emergence of exhibition design – a practice pioneered by avant-garde art movements of the early twentieth century – as a key factor that challenged the “relationship between exhibition spaces, exhibits and spectators/visitors” (p. 123, para. 2). The author also argues that the use of technology has historically led to a redefinition of these relationships which are still in flux today. An example he gives of this is how technology has provided audiences with a channel to bring art, and exhibits, into the home – and this can be as mundane as a series of reproductions on the walls of one’s home to a CD-ROM (pp. 128-129). I was most enchanted by Huhtamo’s essay because in my own view, exhibition design is instrumental in displaying art and cultural heritage. I believe that smoke and mirrors and lots of illusionistic cheap tricks are absolutely necessary in presenting art as they constitute an entry point into new “ways of seeing” and invite viewers to reconsider and rethink what they think they know. Citing Gell (1992), Isaac (2008) has discussed how this can be problematic if we view such strategies as “technologies of enchantment” that cast a spell over us and mystify reality (p. 291. para. 2).

PDQ: How do the magical tricks of technology enhance or disrupt our experience of art?

(RR #2) Bandelli (2010) offers some alternative examples of how virtual museums can augment and extend the physical setting of a museum space by proposing to look at what he calls the “social space” that can seamlessly be created between the ‘real’ activities and the ‘virtual’ experiences. To illustrate, he cites two major examples. First, one where students worked on their projects in computer labs located inside a science museum. Second, a virtual exhibit system that provided contextual information on a need-to-know basis. The author argues that in these scenarios, the social space is increased rather than reduced (cf. isolation). The key, he suggests, is to take into account how technology can complement the function(s) of the space in which it is implemented: to “understand social actions in space and time” (p. 152, para. 1).

PDQ: Can physical space and virtual space be combined to form a new ontological experience that does not serve to isolate the museum visitor?

(RR #3) Müller’s (2010) article extends a similar argument, except that his concern is with expanding the reach of the museum exhibit rather than enlarging the social space of its audience. Virtual space and physical space, he writes, provide different frames of reference for museum artifacts or collections and it is because of this difference in their discursive function that museums can provide the public with multiple ways to understand what they are seeing (cf. modes of reception). This, he says, is in keeping with the museums’ shift “from object-centered to story-centered exhibitions, while still maintaining the importance of the real object experience” (p. 297, para. 7). Aside from providing several examples of how digital technology can be more or less successfully applied to museum exhibits, Müller suggests seven features that he identifies as “necessary for the development of online exhibitions: space, time, links, storytelling, interactivity, production values, and accessibility” (p. 301, para. 1).

PDQ: Can you think of other features or medium affordances that could be identified to make the best use of digital technology when designing virtual exhibits or virtual museum space?

Take your pick or let’s do them all. I am looking forward to your contributions and invite you to forcefully push back and debate on issues related to week #7’s readings and presentation. And please feel free to interrupt me as often as you would like during the seminar…as well as demand that I immediately go to a URL of your choice. This week, your wish is my command: Let me be thou’s humble servant in thy seminar.

Week #7: possible themes for class discussion (feel free to add to this or state your preference(s) in class):

- subversive art practices in the context of virtual exhibits and venues;

- the notion of “essence” of cultural heritage (cf. “essentialism” applied to cultural heritage);

- experiencing architectural cultural heritage virtually vs. physically;

- how does technology affect our experience of art (cf. Gell’s “enchanted technology”);

- the ontological experience that results from virtual space combined with physical space;

- looking at the affordances of digital media to understand its potential in virtual exhibits.

Sources

Cameron, Fiona (2010). The politics of heritage authorship: the case of digital heritage collections. In Y. Kalay, Kvan, T. & Affleck, J. (Eds.), (pp. 170-184), New heritage: new media and cultural heritage. London and New York: Routledge.

Gansallo, Matthew (2002). Curating new media. In R. Parry (Ed.), Museums in a digital age (pp. 344-350). London and New York: Routledge.

Gell, Alfred (1992). The technology of enchantment and the enchantment of technology. In J. Coote & Anthony Shelton (Eds), Anthropology, art and aesthetics (pp 40–66). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Huhtamo, Erkki (2002). On the origins of the virtual museum. In R. Parry (Ed.), Museums in a digital age (pp. 121-135). London and New York: Routledge.

Bandelli, Andrea (1999). Virtual spaces and museums. In R. Parry (Ed.), Museums in a digital age (pp. 148-152). London and New York: Routledge.

Isaac, Gwyneira. (2008). Technology becomes the object: The use of electronic media at the national museum of the American Indian. Journal of material culture 13 (3): 287-310.

Lewi, Hanna. Designing a virtual museum of architectural heritage. In Y. Kalay, Kvan, T. & Affleck, J. (Eds.), (pp. 261-274), New heritage: new media and cultural heritage. London and New York: Routledge.

Lowenthal, David. (1994). Conclusion: archaeologists and others. In P. Gathercole & D. Lowenthal (Eds.), The politics of the past (pp. 302-314). London: Routledge.

Müller, Klaus (2010). Museums and virtuality. In R. Parry (Ed.), Museums in a digital age (pp. 295-305). London and New York: Routledge.

Silberman, Neil (2008) Chasing the unicorn? The quest for ‘essence’. In Y. Kalay, Kvan, T. & Affleck, J. (Eds.), (pp. 81-91), New heritage: new media and cultural heritage. London and New York: Routledge.

Wacławek, Anna (2011). Graffiti and street art. New York : London : Thames & Hudson.

Standard

February 11, 2012 by jeremyClose Encounters of a Virtual Kind

Second Front - "The Last Supper" (2007)- A performance-art group in Second Life. My avatar is located in the middle of the table (pink hair)....

This post deals with Reading Week’s assigned readings which include:

Andrea Bandelli. Virtual Spaces and Museums. Originally in Journal of Museum Education, Vol. 24, 1999. p. 20.

Muller, Klaus. Museums and Virtuality. Ch. 29. Originally in Curator. Vol. 45, no. 1, 2002, pp. 21-33.

Neil Silberman. Chasing the Unicorn? The Quest for “Essence” in Digital Heritage. New Heritage Ch. 6. pp. 81-91.

The recurring theme throughout these readings is that virtuality is more of a museal sequence of experiential “encounters” (Muller 2002:296-297) that can be an acceptable surrogate for the (lack of) available “real” museum artifacts. Since these artifacts are rarely really on display or available to the public anyway (as Muller notes in his Last Supper excursion in MIlan) (Muller 2002:295) and that scholars usually only have access to printed reproductions of artifacts (Bandelli 1999:140-150), the aura has already been sufficient virtualized to become a “real” museum experience. Muller voices the general public frustration that museums often do not have the sought after artifact on display after advertising it (Muller 2002:295) – as most have gone into databases anyway. None of these writers feel that this virtualization is a bad thing, per se. Since museums hardly show the original artifact due to physical safety reasons, the virtual surrogate is really all one has to refer to. It just means that Walt Benjamin was right in forcing the visitor to re-evaluate the relative authenticity of the “original” since we only really have access to the reproduction which may as well be just as real or even more real experientially then original (Muller 2002:298). I am surprised that none of these authors mentioned Baudrillard’s hyper-real notions of simulacra being more real than real. The concept of the simulacra is clearly what all of these authors are tacitly referring to. What I like is how Muller and others acknowledge that the digitization process that most museums engage in is more than a mere reproduction technique (Muller 2002:296). Muller seems to support Levy’s concept of the virtual as being a new synthetic reality rather than as a secondary one subordinate to the “authenticity” of the “real”.

Interestingly, many see museums as a very “real” (rather than synthetically real) civic and sacred space (Muller 2002:297) and so, the museum site in principle, has power as a physical presence. As a result, the museum seems to be the final resting place for the “authentic” (Ibid.). The reason that museums were “trusted cultural institutions” had to do with the myth that the artifacts were “material witnesses” (Ibid). And yet, over the decades, there has been a historical transition from museums being material repositories to becoming immersive story-telling environments (Ibid.). I recall as a kid in the 1970s and 1980s that the Royal BC Museum was a fantastical story-telling space and the authenticity of the reproductions (such as in the 19th century “old-town”) seemed just as pedagogically potent – if not more so – than merely showing the genuine article in a hermetically sealed glass case. The pleasure of visiting this museum was more than social or a desire to connect with authenticity, it was to be immersed as an agent in a world that represented the past – independent of technological novelty (except for the “Water Wheel” exhibit) (Bandelli 1999:148). To experience the essence of the authentic past “[…] on reflection, seems a chimerical goal” as it always “eludes our grasp by changing its form” (Silberman in Kalay et al 2008:83) and so because of this, I place little value in a true connection with the past when going to a museum. It did not even matter that I had access to the museum’s own direct institutional resources and the benefit of such access (Bandelli 1999:149) would not matter to me in a cyberspace version of the museum either unless I had direct ambitions as a curator. These spaces are inherently virtual spaces – at least the more successful ones are. In my opinion and based on my close encounters with the synthetically authentic at the Royal BC Museum, the Disneyfication of museums in general is not an intrusion of museum culture (Muller 2002:303), it helps define the museum as a social space that is equivalent to the narrative and social affordances of pure cyberspace virtual environments (Bandelli 1999:150).

I would like to wrap up this blog post by quickly mentioning how Bandelli believes that the social aspects of a museum experience is thwarted through the virtualization of audio-tours etc (Bendelli 1999:150). I agree with him as I think one needs to explore an immersive world seamlessly as a free-agent in order to enhance the willing suspension of disbelief (Coleridge 1817). Perhaps when intelligent agents truly become interactive guides and address a net-worked chat channel either with a headset or with ambient spatially-distributed speaker configurations with other participants via augmented overlays (holograms?), will the museum’s virtuality become more social in nature.

Standard

February 7, 2012 by dianaOur Children in a Post-Nuclear World

This is really interesting in terms of discourses about “our children” in a post-Nuclear world:

watch?v=dDTBnsqxZ3k&feature=fvwrel

The “Daisy” TV ad that Johnson ran against Goldwater in the 1964 US presidential campaign, cited as the first televised political attack ad.

Standard

February 5, 2012 by kateDigital Cultural Heritage: access, documentation, and the intangible…

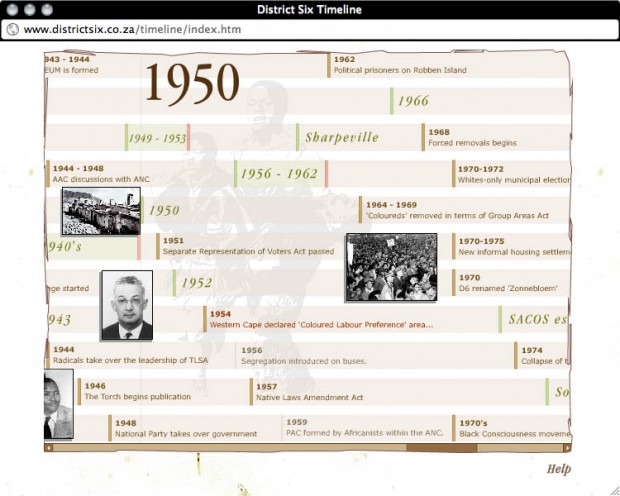

Abungu (2010) paints a picture of the contemporary museums in post-colonial Africa as working to move away from “the old style of exhibition (eg. Dusty objects hidden in glass cases)” (181), and to address the changing face of African society that museums now represent. Part of decolonization, she argues, is a move away from a western museum model, and the positioning of the museum as a tool for social and cultural development. Capetown’s District Six Museum, for example, represents a shift from a focus on objects to the memorialization of the atrocities committed under apartheid––a move from exhibiting tangible heritage to featuring, promoting, and actively documenting and communicating intangible heritage in digital form. Digital cultural heritage from her perspective has the potential to be an agent in the social and cultural work of the museum, telling stories formerly denied heritage value by an oppressive regime, breaking down walls of institutions and creating access for the marginalized; at the same time, its reach is limited by aging telecommunications infrastructure, lack of access to Internet and computers, and conditions of poverty. Abungu’s article points to the role of new media in facilitating access to digital cultural heritage (see Christen’s 2009 piece, and my piece (2009) assigned for this week as well) and the challenges of access outside of urban centres.

Abungu (2010) paints a picture of the contemporary museums in post-colonial Africa as working to move away from “the old style of exhibition (eg. Dusty objects hidden in glass cases)” (181), and to address the changing face of African society that museums now represent. Part of decolonization, she argues, is a move away from a western museum model, and the positioning of the museum as a tool for social and cultural development. Capetown’s District Six Museum, for example, represents a shift from a focus on objects to the memorialization of the atrocities committed under apartheid––a move from exhibiting tangible heritage to featuring, promoting, and actively documenting and communicating intangible heritage in digital form. Digital cultural heritage from her perspective has the potential to be an agent in the social and cultural work of the museum, telling stories formerly denied heritage value by an oppressive regime, breaking down walls of institutions and creating access for the marginalized; at the same time, its reach is limited by aging telecommunications infrastructure, lack of access to Internet and computers, and conditions of poverty. Abungu’s article points to the role of new media in facilitating access to digital cultural heritage (see Christen’s 2009 piece, and my piece (2009) assigned for this week as well) and the challenges of access outside of urban centres.

Abungu’s analysis of the museum in post-colonial Africa speaks to Fiona Cameron’s assertion that heritage discourse––which has come to include digital heritage––is culturally and politically produced. She argues:

“Choices as to what to keep and criteria in which to define objects are made at the expense of others and as Hall (2005) suggests is one of the ways a nation slowly constructs a collective memory of itself. Clearly the same is true for digital heritage items. The value of the past for the future and the nation hinges on these essentialized meanings” (Cameron 2008:177).

Reminding me of Jeremy’s post last week, Cameron argues that Western societies have been largely object centered, “where notions of heritage place the accumulation of objects of critical importance is the transmission of cultural traditions” (Cameron 2008:178). She contrasts this object-orientation with societies that are concept centered, in which objects are preserved because of their ongoing functionality, and in which cultural is transmitted orally––what is now known and codified by UNESCO as the intangible cultural heritage. As tangible and intangible heritage are being digitized in the name of preservation, they are rapidly being inducted in a process of “heritigization”, which Cameron sees as reinforcing Western paradigms of historical materiality (think Walter Benjamin). This process of heritigization is further steeped in the discourse of loss, in which digital heritage is valued if it is perceived as being lost to posterity, rather than for its value in the present. What are the consequences? Should heritage preservation be about more than the archiving of a record, of documentation, of an object? What is the role of the digital object in heritage preservation, and in keeping intangible cultural heritage alive and reproducing? How do we understand the digital surrogate in relation to the original?

Alonzo Addison (2008) reflects on the need to safeguard heritage’s endangered digital record through the lens of built-heritage documentation. By his definition, virtual heritage is practice oriented: “the use of digital technologies to record, model, visualize, and communicate cultural and natural heritage” (2008:27). This work is producing digital heritage, which itself is threatened by changing technologies, data storage challenges, and a lack of interdisciplinary collaboration and cooperation. Addison’s work, scanning and digitally documenting endangered world heritage sites, is grounded in discourse promoted by the UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, which “formalizes the concept of places of ‘outstanding universal value’ to all humankind and proceeds to encourage their protection and preservation for all” (2008:30). (Note that intangible cultural heritage was only formalized as a heritage concept in 2003). As you can see in this message from the Irine Bokova, the Director General of UNESCO, on the 40th Anniversary of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, the discourse of universal value is alive and well (but of course depends on ongoing international support. Lack of support makes even more visible the ideological underpinnings of world heritage policy…). World Heritage, according to UNESCO, “is a building block for peace and sustainable development. It is a source of identity and dignity for local communities, a wellspring of knowledge and strength to be shared. In 2012, as we celebrate the 40th Anniversary of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, this message is more relevant than ever.”

Addison’s chapter is well illustrated in this recent TED talk by Ben Kacyra (below), who has developed technologies for extremely fast, high resolution 3D scans of heritage spaces, and is currently building a global network with the goal of scanning and documenting all of the world’s endangered heritage. He reiterates that the loss of world heritage––heritage that essentially belongs to us all as humans on earth––is a loss of the stories (the intangible) that these places represent, and a loss of the collective memory that tells us who “we” are. Without our heritage, he asks, how will we know who we are?

I am interested in one particular moment in the talk, when he describes how the scanning and digital modeling of a ritual structure in Uganda was put to use after the original structure burned down. In this case, I see potential for intangible cultural heritage–the knowledge of how to build a traditional form of architecture––to actually be revived with the use of digital documentation. Because of the 3D model, the structure could be rebuilt, and in the course of doing this, new knowledge was generated, and potentially passed on. So, what is the relationship of the digital file to the original? In this case, the digital file could be used to recreate the original, but most of the scans by CyArk will simply be archived. What will be documented along with them? Are they removed completely from their contexts of production—do they maintain a connection to the original or do they take on new heritage significance on their own?

Finally, Last week we discussed the news that the US Library of Congress will begin to archive all tweets being generated through the platform Twitter. The response to this announcement is interesting, coming from those who are eager to be able to search the archive, to those who feel that their privacy has been invaded (I never signed up to be archived by the Library of Congress!), to those who think that archiving more than 50 million tweets every day is a colossal waste of financial and human resources. The New York Times discusses a new kind of researcher—the twitterologist––and indeed, the data is tremendously useful for researchers of all kinds, but is it heritage? Why or why not?

Lyman and Besser (2010) discuss the Internet Archive as representing another example of the desire to preserve and archive as much of the emerging digital heritage as possible, before it is “lost”. Through the Wayback Machine, over 150 billion web pages are available, reminding users of the dynamic and contingent nature of the Internet—it is always changing, or more accurately, we are always changing it. Is it heritage?

What heritage should be saved? Who should save it? Does documentation of heritage amount to preservation, to ‘safeguarding’? How is local heritage translated into heritage of “universal value”, and what are the implications? What of the question of cultural property, of intellectual property rights, and copyright in this mess? I like Larry Lessig’s TED talk, in this regard, for the way it spells out some of the legal and cultural foundations of current IP and copyright law. But, to connect a thread back to some of our earlier conversations, what are the some of the ethical issues related to digitizing and making formerly analogue heritage digital—should digitized cultural documentation automatically be inscribed as heritage of universal value, that should be open for access by all… or can we come up with alternatives that contest this emerging norm?

There is clearly a lot to discuss in the seminar this week, from digital cultural heritage as access, as documentation, as ethical and legal touchstone, as cultural policy, as memory and identity, to its representation of shifts in relations of power… I look forward to your thoughts on this post or any of the readings for this week.

References Cited:

Abungu, Lorna (2010). Access to Digital Heritage in Africa: Bridging the Digital Divide. In Museums in a Digital Age. R. Parry, ed. Pp. 181-185. London and New York: Routledge.

Addison, Alonzo (2008). The Vanishing Virtual: Safeguarding Heritage’s Endangered Digital Record In New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage. Y.E. Kalay, T. Kvan, and J. Affleck, eds. Pp. 27-39. London and New York: Routledge.

Cameron, Fiona (2008). The Politics of Heritage Authorship: The Case of Digital Heritage Collections. In New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage. Y.E. Kalay, T. Kvan, and J. Affleck, eds. Pp. 170-184. London and New York: Routledge.

Christen, Kimberly (2009). Access and Accountability: The Ecology of Information Sharing in the Digital Age. Anthropology News (April):4-5.

Hennessy, Kate (2009). Virtual Repatriation and Digital Cultural Heritage: The Ethics of Managing Online Collections. Anthropology News (April):5-6.

Lyman, Peter, and Howard Besser (2010). Defining the Problem of Our Vanishing Memory: Background, Current Status, Models for Resolution. In Museums in a Digital Age. R. Parry, ed. Pp. 336-343. London and New York: Routledge.

Aside

February 2, 2012 by kateOpenMOV

I had a good chat with Bardia today about his final project. One of the resources that we discussed is the MOV’s OpenMOV archive, which lets you search the contents of the museum’s collection. If you are trying to imagine how to involve the MOV, neon signs, or other objects from the collection into your project proposal, this is a useful tool. I am looking forward to discussing the final project with you all next class.

Standard

February 1, 2012 by kateResponse Paper Details

Greetings all, here are some additional details about the response paper, due next week. These are a summary of the discussion in our last seminar.

Standard

February 1, 2012 by kateAdobe Museum of Digital Media

Check out the Adobe Museum of Digital Media… the virtual museum of virtual museums… what do you think?

Standard

January 31, 2012 by kateCreative visualizations of a photographic archive… The Whale Hunt

Jonathan Harris’ The Whale Hunt.

I wrote a review of this site, which you can find here: http://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/mar/article/view/97

Standard

January 31, 2012 by kateHigh-Resolution Object Photography

Interesting photography of museum collections…. http://synthescape.com/media/umista/