This week’s chapters – Body, Senses, Time and Space – are interesting to put in relation. In setting the ground for their argumentations, the authors reference oppositions which can be seen as contextualized versions of a similar issue:

If human bodies are in some cases factual objects to be discovered and analyzed, they are at the same time the very medium through which such knowledge is attained.

Body – CTMS, p. 20

The senses both constitute our “sense” of unmediated knowledge and are the first medium with which consciousness must contend.

Senses – CTMS, p.88

two conceptions of time and space (and their relationship) have seemed to dominate: objective, mechanical, and mathematical models … and qualitative, subjective models …

Time and Space – CTMS, p. 101

This is of course an old divide, and it would be pointless to try to resolve it as an either-or problem. Caroline Jones provides maybe the most interesting dialectic argument to reconcile the apparent tension:

the senses are complex cognitive systems in which there is no clear separation between, for example, the “medium” of air, the “message” of sonic information, and the intricate body system that interprets sound waves as language (CTMS, p. 91).

Sound and psychoacoustics provide indeed a marvelous example where the “message” undergoes a series of transformations even before reaching the hair cells of the inner ear. The sound is filtered by the mass of the head, and subtle reverberations which depend on the specific shape of the outer ear. As the sound waves propagate into the ear canal, their medium then shifts from air to tissue, to bone, to liquid, to hair.

This is transmediation in a very physical sense, and we see that dualities such as: inner / outer, medium / message, subjective / objective, gradually dissolve as we examine a process in increasing detail.

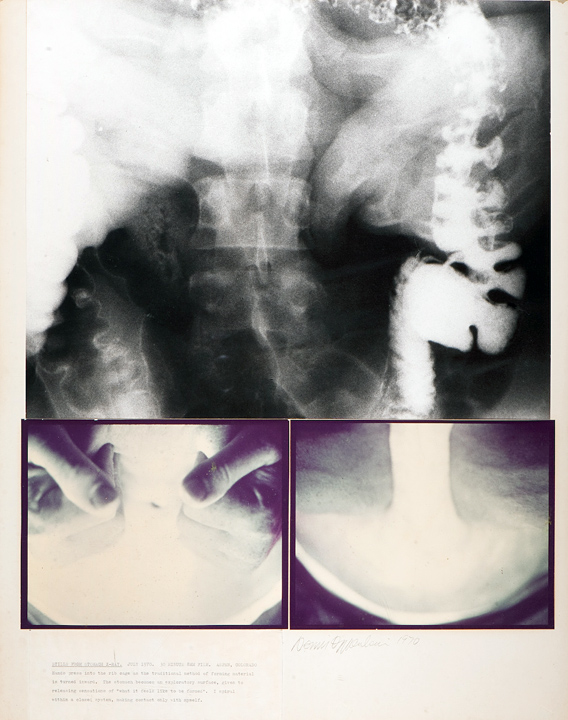

Dennis Oppenheim’s Stomach X-Ray (AEM, p. 143) seems to delight in confounding these abstracted categories. The body here is a literal medium to be shaped like clay. And “the artist is both subject and object, artist and artwork, as his body is both the image-maker and the image” (AEM, p. 143). Oppenheim’s use of technology – X-ray photos – adds another level of mediation to overcome the opacity of the body and present his “insides” to be exhibited.

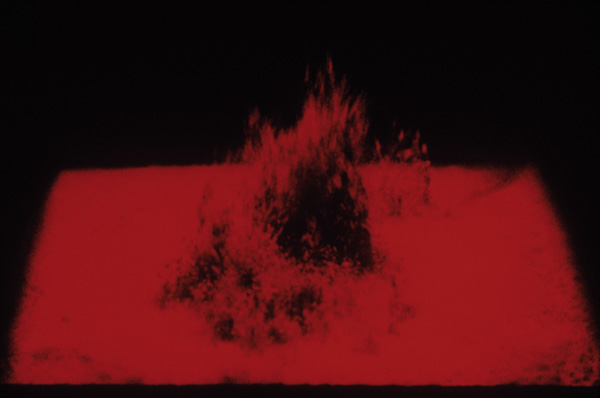

A similar gesture is at work in Jean Dupuy’s Heart Beats Dust (AEM, p. 66). Sound’s affinity for transmediation is taken one step further by making it manifest visually through light and pulsating dust. The source of the sound is the viewer’s heart beat, a reversal of the naïve understanding of the senses as purely inward oriented processes. The piece externalizes and illuminates a pulse which is the condition of life, yet usually unheard. Just as the body is both present and elusive, the dust patterns are revealed but contained in a box.

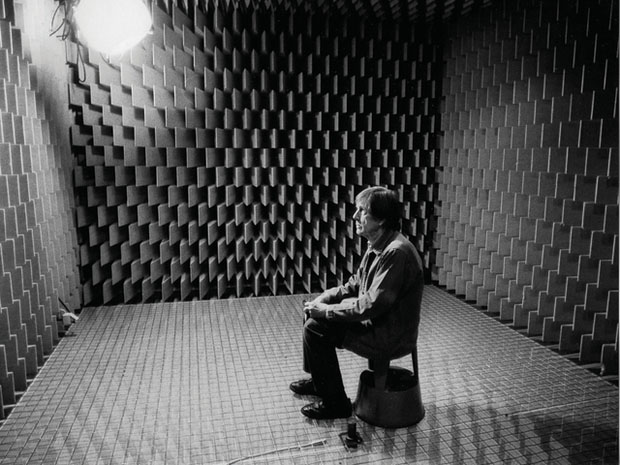

Seiko Mikami’s World, Membrane and the Dismembered Body (AEM, p. 157) is also an exploration of internal sounds, and echoes John Cage’s experience in Harvard’s anechoic chamber. He went there expecting silence, but found instead two sounds: a low one from his blood flow, and a high one from his nervous system. They were always there but it took silence to disclose them. Finding trust in this embodied aural texture that precedes the awakening of consciousness and never recedes, Cage concludes that “one need not fear about the future of music” (Cage, p. 8).

A close parallel in dance is Steve Paxton’s practice of the small dance. Standing in stillness, one gradually realizes that the stillness is never still. A deep physical quieting and careful tuning of the senses reveals a stream of minute falls and recoveries. These postural reflexes are involuntary and happen whether we pay attention to them or not. The practice is part of Paxton’s Material for the Spine: a somatic technique to “[alloy] a technical approach to the processes of improvisation” and “bring consciousness to the dark side of the body, that is, the ‘other’ side, or the inside, those sides not much self-seen, and to submit sensations from them to the mind for consideration” (Paxton).

In Embodied knowing through art, Mark Johnson combines his work on embodied cognition with reflections on the relationship between art and research. Following earlier ideas from John Dewey, he discusses the nature of embodied knowledge, and cautions against the temptation to seek the fixed and immutable. Embodied knowledge cannot be reduced to static collections of facts, but needs instead to be sourced in dynamic processes of inquiry (Johnson).

Transposing these ideas to Paxton’s work with improvisation and composition, we see that what he is composing is himself – a process of neuro-plastic transformation through practice, or what Margaret Wilson calls a re-tooling of the mind (Wilson). Still performing now well into his seventies, Steve Paxton demonstrates what might be, what might come to happen, when you devote a lifetime to a practice.

Two quotes to finish

I am finishing this introduction with two quotes as possible lines of inquiry for Friday. The first is Caroline Jones quoting Ockham on abstraction (what a sharp mind and razor he had). The second is a short and brilliant text by Borges, playing with the map-territory relation.

To abstract is to understand one thing without understanding another at the same time even though in reality the one is not separated from the other, e.g., sometimes the intellect understands the whiteness which is in milk and does not understand the sweetness of milk. Abstraction in this sense can belong even to a sense, for a sense can apprehend one sensible without apprehending another. (CTMS, p. 91).

In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

Jorge Luis Borges, On Exactitude in Science

References

Cage, J. (1961). Silence: Lectures and writings. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan.

Johnson, M. (2011). Embodied knowing through art. In M. Biggs & H. Karlsson (Eds.), The routledge companion to research in the arts (pp. 141–151). New York, NY: Routledge.

Mitchell, W. J. T., & Hansen, M. B. N. (Eds.). (2010). Critical terms for media studies. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press.

Paxton, S. (2008). Material for the spine: A movement study. Brussels: Contredanse.

Shanken, E. A. (Ed.). (2010). Art and electronic media (Reprint edition). London, UK: Phaidon Press.

Wilson, M. (2010). The re-tooled mind: How culture re-engineers cognition. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 5(2-3), 180–187.

Leave me a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.