I am pleased to start off our seminar this term with a discussion of Image, through W.T.J. Mitchell’s essay in Critical Terms for Media Studies (2011).

In doing so, in my seminar presentation I will 1) work through some of the definitions provided by WTJ Mitchell in Critical Terms in Media Studies, highlighting some persistent themes and tensions; 2) consider the ways in which advances in technologies of reproduction have influenced understandings of the image and its potential (looking to Benjamin, Adorno, and Horkheimer); and 3) pose several questions for discussion.

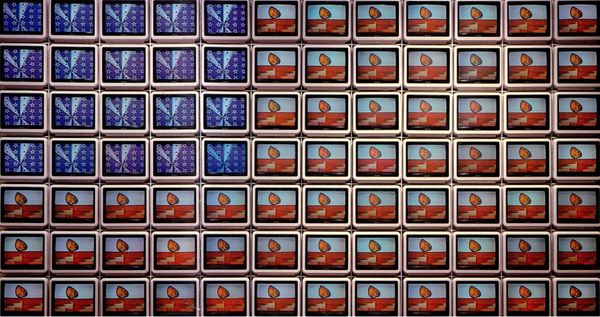

Building on Mitchell’s assertion (following McLuhan!) that artists have always been at the forefront of cultural critique and engagement with new technologies, we will look at a few precedent works. At the same time we will aim to connect these works to a broader conversation around the social, cultural, and political resonances of the ideas and themes that these artists evoke.

http://www.coryarcangel.com/things-i-made/2002-001-super-mario-clouds

He writes:

“New technical media certainly do make for new possibilities in the production, distribution, and consumption of images, not to mention their qualitative appearance. Artists, as Marshall McLuhan observed, are often at the forefront of experimentation with the potential of new media, and earlier media innovations such as photography and cinema, which were widely recognized as inherently hostile to artistic expression, are now firmly canonized as artistic media of the first importance. But media innovation is driven by other factors as well: by technoscientific research, by the profit motive, and by emergency situations such as war. If researchers like Paul Virilio and Friedrich Kittler are correct, one can not understand stereophonic sound without considering the guidance apparatus developed to allow bomber pilots to fly “blind” in a fog, the movie camera without understanding its evolution from the machine gun, or the Internet without considering its origins in military communication (46-47).

I would like us to be able to use these works as jumping off points for our discussion. For me this kind of discussion is an opportunity to practice the following:

1) describing works of art (thinking about materials, composition, technique and technologies) and being able to discuss their materiality or poetics in relation to what artists have to say about the works;

2) engaging with these works as a way to enter into conversation about more abstract ideas and themes that are tied up in media studies;

3) in keeping with the aims of the course to explore the ‘technoanthropological universe’, relating these themes and concepts and aesthetic articulations to contemporary issues and events. As such, I aim to conclude the seminar with a discussion of two recent pieces of research: the first, from MIT, shows how algorithms are able to identify humour in images; and the second, Mary Gray’s broader discussion of the invisible labor of the internet. If you can read these short pieces before the seminar, all the better.

As a side-note, this pre-seminar post is not meant to be a complete representation of what you will do when leading the seminar. My goal here is to encourage everyone to come to the seminar primed for a discussion and to get the discussion happening in some small way off line before hand. So think of these as shorthand notes and a few questions that will get us off to a good start on Friday.

What is an Image?

Why do images have such power to inspire in us such great passions? Mitchell builds his essay on the Image around this question, and I think it makes sense for us to start here as well. He writes, of images,

“To understand their paradoxical status, we will have to take a longer view of images in media, asking what they are and why it is, that, since time immemorial, they have been both adored and reviled, worshipped and banned, created with exquisite artistry and destroyed with boundless ferocity” (p. 36).

We don’t have to look far in time or space to see what extreme violence is provoked today by the image.

Mitchell emphasizes (p. 47) that the Internet, essentially a metamedium that incorporates the postal system, TV, computer programming, telephones, newspapers, advertising, banking, gossip (and he goes on to list more). Images are continuously generated and circulated in this medium, solidifying them as an ongoing and central concern for media scholars.

Mitchell raises several ‘persistent qualities’ of images that give us a way into understanding them better: ‘sensuous firstness’; resemblances; and analog codes. I’d like to review these qualities briefly in advance of our discussion, with the hope that we can use them in conversation about artworks and the meaning of the image, and its modes of production and circulation in the digital age.

According to Mitchell, “An image is a sign or symbol of something by virtue of its sensuous resemblance to what it represents” (39). Following Pierce, It must do more than represent or signify; it has to possess ‘firstness’, the things we perceive before we are aware of representation—eg. color, texture, shape. These are the qualities that allow us to generate a perception of resemblance. But scholars have debated where exactly this ‘likeness’ is to be found—is it in the specific properties of the object, the mind of the viewer, somewhere in between? A Mitchell asks, can’t everything in the end be said to resemble everything else?

Further, images do more than resemble. They can evoke temporality (date, historical style, a depicted narrative); their stillness, he writes, like a web cam or surveillance photo, is “suffused with time” (39).

At the same time, the image itself has always been in motion (think of the camera obscura); actors on stage do not represent themselves, but produce images of characters and actions through imitation.

See: Room With A View – Abelardo Morrell –Camera Obscura from Howard Silver on Vimeo.

Images, it seems, can be “anything that human imagination, perception, and sensory experience is capable of fashioning for itself as an object of contemplation or distraction” (40). Even a room, mediated by technology, can be considered able to ‘see’, as in the video above.

This includes mental images, and with that notion, memory as a medium. If the mind is a medium for the storage and retrieval of images, and all minds are housed in bodies, then, according to Mitchell, “to speak of mental images is automatically to be led into the problem of embodiment, and the material world of sensuous experience, whether it is the generalized “human body” of phenomenology, or the historically marked and disciplined body of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability, and biomedical technology” (41). The image, in this way, is at the center and the periphery of media studies—“images always appear in some medium or other, and we cannot understand media without constructing images of them” (42). For me, this is where our course’s attention to critically reading new media and electronic art feels like an appropriate way to engage with media theory and practices.

Along those lines, through the lens of the image, how can we understand the transformations brought about by digital and computational technologies? Mitchell points to the claim that the digital has rendered the traditional image obsolete. If the image is composed of pure numerical information (digital code), it has become divorced from its ‘sensuous firstness’—its human impressions, resemblances, affects—and is replaced by an image that is first read by machines. This mode of thinking lends itself to dystopian visions of the posthuman, where,

“If man was created in God’s image, and God was remade in man’s… it makes a kind of sense that the invention of artificial intelligence and “thinking machines” would mark the end of the human and image altogether. The posthuman imaginary postulates robots and cyborgs––biomechanical hybrids––as the emergent life-forms of our time” (44).

With these ideas in mind, we will watch Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1968), and see what his still image-based sci-fi narrative of a post-apocalyptic Paris, of memory and confusion, torture and proto-virtual reality, romance and death (it has it all!!) can help us understand about our contemporary sociotechnical predicament.

“La jetée” by Chris Marker from minneapolis on Vimeo.

Add yours Comments – 1

An interesting interview on how we see and interpret images. Georges Didi-Huberman discusses how we define what an image is and the difference historically between images and words: http://rwm.macba.cat/en/sonia/georges-didi-huberman/capsula