Listening to Barry Truax’s Earth and Steel

Spectrogram of the piece

Facts

Barry Truax’s Earth and Steel is an eight channel soundscape composition. The piece uses field recordings from a shipyard in Caraquet, New Brunswick. They were recorded in 1973, as part of the World Soundscape Project’s efforts to document aural environments in Canada and abroad. Earth and Steel was premiered in 2013, at the Royal Naval Dockyards in Chatham, UK.

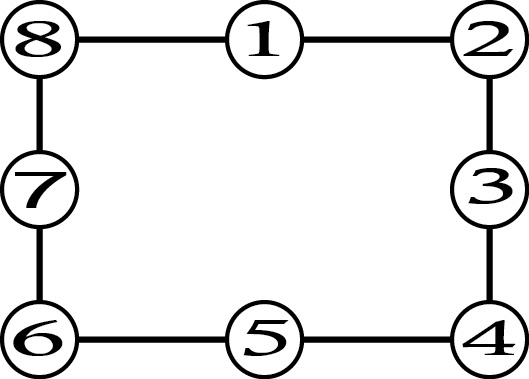

I had the opportunity to hear it performed twice, most recently during ISEA 2015’s Octophonic Soundscape Compositions concert. The piece is also available as a stereo downmix, which I have listened to many times. In a typical eight channel setup for a rectangular space, the speakers are placed in the four corners and in the middle of the four sides of the room.

Preliminary

I am sitting in a room. The lights are slowly fading. As this man-made dusk descends, I find myself finding myself through different senses. I am surrounded by murmurs of friction, materials rubbing against each other, the sounds of bodies shifting and settling, and a hint of expectation echoing mine.

The music has not started yet. But the deepening quietness is as much a part of the concert as are the forthcoming pieces. David Toop writes that sound art’s “point of origin is silence and listening” (2005), a state of being which I would apply equally to the creation of a work and its experience. In this quieting room, we, the audience, are tuning ourselves. Just like musicians in a symphonic orchestra preparing to play, we are getting ready to experience.

As we offer our attention, we co-create a space of mindfulness, supporting a heightened quality of hearing. Salome Voegelin points out that “listening is not a receptive mode but a method of exploration, a mode of ‘walking’ through the soundscape/the sound work” (2010, p. 4); an extension to aural modalities, of Michel de Certeau’s meditations on pedestrian tactics.

I am close to the center of the space. If this was a dance performance I would seek instead the front row, close to the liminality of the fourth wall, to engage more viscerally with the physicality of the dancers. But the eight speakers surrounding us foster a different topography of attention. The privileged point of listening is in the center, equidistant from all speakers, a radial rather than frontal way of structuring space.

The concert features six pieces, closing with Earth and Steel. These are all set compositions, indefinitely reproducible schizophonic recordings, to borrow Murray Schafer’s term (1977). Yet there is an undeniable performative quality to the event. Each point of hearing is singular. The performance space has a unique acoustic signature, mediating all sounds propagating through it. Our actual bodies alter the overall acoustic balance, each a slight dampening filter, absorbing some of the vibrations. Having had a chance to witness the care required to set up and tune all of the audio equipment, I appreciate how much skill goes into creating this aural experience: a crafted and ephemeral rendering.

Experience

Earth and Steel begins with ambient sounds from the shipyard, a very resonant space. The sense of expansive volume is immediate and I realize that while such an acoustic signature is not unfamiliar to me, I am relating it to experiences of other spaces altogether: churches and cathedrals. Schafer characterizes these sacred structures as “acoustic machines” (1977), designed to amplify the voices of choirs and officiating priests, and overlaying them with numinous qualities.

The reverberance of the shipyard however is incidental, a consequence of the need for open space and the scale of the constructions it shelters. And the sounds of labour it accentuates are much different from sounds of worship.

A haze of ambient noise, coloured by low hums, forms the aural background of the shipyard. Against this backdrop, a variety of percussive impacts, metal against metal mainly, punctuate the soundscape. The variety of these industrial sounds surprises me. There is a range of pitches and timbres, placed far or close, and in various directions around me.

I experience a clear sense of human agency transmediated to sound, which calls to mind a multitude of verbs: tapping, striking, dropping, slamming, banging, dragging, whirring… I am hearing intentions, gestures, and the materiality of manipulated objects. A new sound stands out, like a powerful switch, metallic and humming from the electric power coursing through it.

A slow crescendo in the loudness and density of impacts builds up. Through repetitions and variations, the discrete occurrences slowly aggregate into patterns which I begin to recognize. And then a bang, particularly powerful, extends uncannily into a trail of sustained shimmering.

From there on the piece shifts. Successive impacts are similarly extended through superposed layers of audio processes. As the sounds ring and decay in slow waves, the mundane soundscape of the shipyard is flooded with warm beating timbres and ethereal overtones.

Drifting for associations leads me again to a very different social context. The long inharmonic sweeps are reminiscent of the massive church bells of old European churches. The tangent is worth pursuing, because it highlights a connection between these aural qualities and an underlying materiality of metallurgy and labour.

In the last chapter of Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Andrei Rublev, we witness the casting of a bell, in an area ravaged by plague. The bell could easily be reduced to a religious symbol, and the prince who orders it certainly sees it as nothing but a status symbol to strengthen his claim to power. Tarkovsky however takes us slowly through the painstaking process of making such a larger than life artefact. The casting requires clay, wood, fire, air, water, and ore, poured into the earth, then unearthed, revealing a shell of stone and dirt. Broken out of this chrysalis, and hoisted out of its pit and into the air, the bell finally rings.

For the destitute survivors of the plague, and the young boy who leads the making through sheer determination, the bell is a catalyst which mediates the coming together of many towards its creation. While not quite as dramatic, the shipyard stands as a similar place of communal making, where the resonant sounds of vibrating steel are anchored in physical labour.

Andrei Rublev – Bell casting

Andrei Rublev – Bell ringing

Techniques

Truax uses a technique called convolution to process the sounds of the shipyard. Convolution can be used to simulate the reverberant properties of a space. An impulse response is first recorded, i.e. a sharp sound like a clap and its pattern of decay as it bounces and eventually dissipates. The impulse response characterizes the acoustic properties of the space, and convolving another sound with it simulates the reverberations which would transform the sound.

Truax however uses the technique more creatively, and convolves sounds with themselves, through multiple iterations. The process tends to highlight and extend dominant frequencies, while dissolving transient patterns and attacks. He then weaves these elements into an intricate layering of processed and unprocessed sounds. Remarkably, the shimmering waves of sound which are so mesmerizing in the finished piece are already present in the original sounds, small timbral seeds made tangible through processing and composition.

Space, environment

Old systems of correspondences between artistic disciplines and categories such as time and space, have been shuffled and upended by contemporary practices, as well as widening perspectives seeking to include non western traditions. The historical characterization of music as purely an art of time for instance (Mitchell & Hansen, 2010, p. 103), is certainly undermined by soundscape composition in general, and in further specific ways by Earth and Steel.

Beginning with the most obvious, there is the use of spatial diffusion, placing or moving sounds around the audience through the eight channels. The technique reflects a more fundamental aspiration in soundscape composition to capture or recreate a scape. This is more than simply mapping sounds to locations, but does involve a sense of space and place. In a review of works created at SFU, Truax distinguishes three structural approaches:

- Fixed perspectives, where “time is created by the movement of the sound, not that of the listener” (2002, p. 8).

- Moving perspectives, emphasizing a sense of journey and “smoothly connected space/time flow” (2002, p. 9)

- Variable or discontinuous perspectives (2002, p. 11).

Earth and Steel falls within the first category. The piece unfolds in the set environment of the shipyard. But this fixed perspective does not preclude a strong sense of space. The resonant quality of the building, compounded with the resonant properties of the materials, saturates and discloses the expanse of the shipyard, which is almost singing back to the worker’s ongoing tapping, hammering and banging.

Truax’s use of convolution brings this responsive acoustic property to the foreground, giving it at times a full independent voice from its percussive sources. The piece then becomes an interplay between metallic sounds of human agency, and the reverberating voice of the enfolding shipyard. Such attention to the environment as both a place where the music unfolds, and an instrument through which it is created, echoes similar explorations in contemporary practices (Pauline Oliveros, Stuart Dempster and David Gamper’s Deep Listening Bad for instance); and cultural forms such as the vocal soundings of their environments by Tuvan singers (Levin, 1999): in a cave (track 15, Cave Spirits), or in front of a cliff (track 16, Kyzyl Taiga, Red Forest).

Tuva, Among the Spirits: Sound, Music, and Nature in Sakha and Tuva

Time, scales, memory

Curtis Roads distinguishes no less than nine scales of time at which musical compositions operate (2001, p. 3). The extreme ranges, infinite at one end, infinitesimal at the other, are maybe listed more for the sake of being complete than actual relevance. But the intermediate scales are useful to consider, in correspondence with the program notes for the piece:

Earth and Steel takes the listener back to a time a century ago when large steel ships were built in enclosed slips, and rich metallic resonances rang out. These larger than life sounds reflected the sheer volume of the ships themselves that dwarfed those who were building them. However, just as the piece progresses and ends, these soundscapes now have become increasingly distant memories, only to be re-imagined in museums.

Working from recordings suggests an implicit remediation of the past through technological means of reproduction. Earth and Steel stands out though, through its deliberate reach back through time: composed in 2013, using original recordings from 1973, with an intention of recreating a century old soundscape.

Memory, and the struggles or disappearance of industrial sites such as the Caraquet shipyard, provide a narrative framework through which to hear the piece. The shipyard incidentally has been in the news, going through cyclical attempts at revival and periods of downturn:

Bas-Caraquet shipyard woes lead to 28 lay-offs

Truax reflects this narrative, and corresponding supra scale of time, into the shorter time scales of sound objects and processing (Truax, 2014). In its usual use as reverberation, convolution superposes a myriad of delayed reflections, as a sound bounces through the geometry of a space. In a sense, each reflection is a memory of the original sound. The image becomes even stronger when a sound is self-convolved, like a memory sustaining itself through reflexive loops of recollections.

Through these processing techniques, the piece not only dissolves traditional categories such as time and space into a “space-time continuum that is infinitely flexible and malleable”, but also leverages new possibilities afforded by computers through which “time and space will take on quite new forms” (Mitchell & Hansen, 2010, pp. 105, 106).

Materiality

Discussions on the materiality of sound seem to settle on distinct aspects of auditory processes and sources. Raviv Ganchrow for instance, peers into the seemingly intractable gap between acoustic waves and perceived sound (2009), contextualizing the usual tension between first‑person and third-person perspectives to the sense of hearing. Elodie Roy focuses on the materiality of media technologies and infrastructures used to record and disseminate sounds (2015). While Michel Chion discusses the use in film of materializing sound indices: “to ‘feel’ the material conditions of the sound source, and refer to the concrete process of the sound’s production” (1994, p. 114).

Listening to Earth and Steel, I find myself drawn to consider the latter which echoes what Mitchell and Hansen call the materiality-effect: “the end result of the process whereby you’re convinced of the materiality of something” (2010, p. 51). From that perspective, the intangible nature of sound as a vibration becomes an asset: an ethereal materiality.

The term ether, in spite of its current connotations, actually refers to a substrate. It was the crux of a major scientific debate – the existence of luminiferous aether – which lasted well into the 20th century. The question was whether light has a medium through which it propagates. The idea was gradually disproved after the Michelson-Morley experiment of 1887.

Sound on the other hand certainly does require a medium, and it propagates through it by engaging all of it. Unlike sight, limited by opacity, and touch, limited by solidity, sound is not restricted to surface appearances. When I hear a large sheet of steel hit by a metal tool in the piece, I am hearing its mass, its shape, the hardness of the impacting tool, and the elastic properties of its material. The dynamic patterns of attack and timbre even evoke a sense of the gesture behind the sound.

Coming back to Andrei Rublev, when the bell is unearthed, still ensconced in its shell, the foreman first examines it by tapping. He uses sound to reach through the shell and sense the bell within.

References

Chion, M. (1994). Audio-vision: Sound on screen. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Ganchrow, R. (2009). Hear and there: Notes on the materiality of sound. OASE Journal for Architecture, 78, 70–81.

Levin, T. C. (1999). Tuva, among the spirits: Sound, music and nature in Sakha and Tuva [Audio CD]. New York, NY: Smithsonian Folkways.

Mitchell, W. J. T., & Hansen, M. B. N. (Eds.). (2010). Critical terms for media studies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Roads, C. (2001). Microsound. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Roy, E. A. (2015). Media, materiality and memory: Grounding the groove. Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing.

Schafer, R. M. (1977). The tuning of the world. New York, NY: Knopf.

Toop, D. (2005). The art of noise. Tate Etc, 3.

Truax, B. (2002). Genres and techniques of soundscape composition as developed at Simon Fraser University. Organised Sound, 7(1), 5–14.

Truax, B. (2014, December). Interacting with inner and outer sonic complexity: From microsound to soundscape composition. Retrieved from http://econtact.ca/16_3/truax_soniccomplexity.html

Voegelin, S. (2010). Listening to noise and silence: Towards a philosophy of sound art. New York, NY: Continuum.

Leave me a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.