Imagine a man and his little daughter. They are playing a game on the banks of a river in Surrey. A game of matching a single sound of their language to a graphic symbol. After a few hours of scribbling furiously, making funny noises and faces, and generally having intense fun, they will have invented most of the letters in the Latin script, and more precisely, the English alphabet.

The man is called Tegumai, his daughter Taffy, and they lived thousands of years ago in pre-historic England, and in the imagination of Rudyard Kipling who immortalized them in his classic “How The Alphabet Was Made.”

Kipling wrote this story for his children back in the beginning of 20th century. He was not a linguist, only a brilliant writer, but he did touch on a few important issues that came to be discussed by scores of linguists, philosophers, and semioticians for the whole 20th century and beyond.

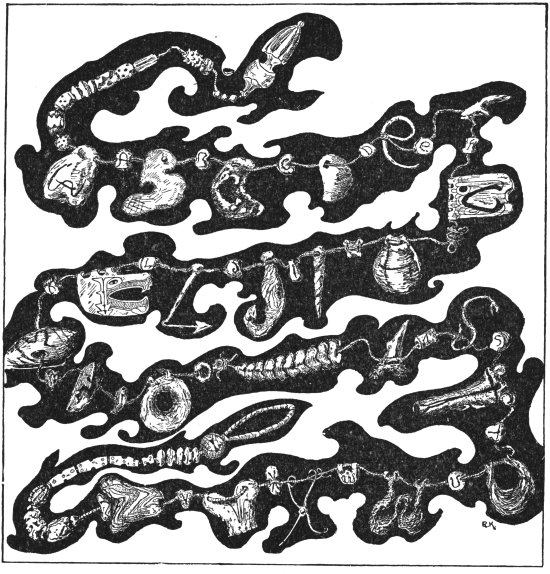

There is a prequel to all this, though. In the preceding story in the book, “How The First Letter Was Written”, Taffy scratched a description of her father’s predicament (broken spear) on a tree bark and sent that to her mom with the help of a stranger who didn’t speak her language. She was only hoping that her mother would understand the situation simply by looking at the drawings, and therefore bring a spare spear to her father. What followed, however, was a hilarious and very embarrassing situation. The Neolithic ladies and Taffy’s mother didn’t quite get the depiction and almost brought about a war with a neighbouring tribe. As a result, this first attempt of pictorial representation of concepts was swiftly abandoned in favour of a writing system that would change the lives of those prehistoric people.

While, of course, this is not exactly how writing came to be, there are a few important notions here that are nevertheless true. First off, as any linguist would describe it, the alphabet that Tegumai and Taffy devised is a shining example of an alphabetical – or phonological – writing system, albeit entirely fictional in terms of methods of creation. As such, it is comprised of letters, each representing a single phoneme (a unit of sound) of the language. And with the phoneme being the most basic building block of syllables, and respectively, words, this writing system is a much better representation of the oral speech that constitutes a language than the pictograms used in Taffy’s drawing from the previous story. This, at least, is the implied message that Rudyard Kipling seems to convey.

* * *

For Lydia Liu, there is a clear historical trend of ascribed supremacy of phonographic (or alphabetical, as she terms them) writing systems (Greek, Latin, Cyrillic, Arab, Hebrew) over pictographic – or logographic – writing systems (ancient Egyptian, Chinese and Japanese). Western thinkers, philosophers and linguists, she claims in her essay on writing, have had the tendency to denigrate non-alphabetical writing as not civilized or cultured. For them, the alphabetical writing is the pinnacle of evolution of writing – starting with pictographs and ideographs, through syllabic, and ending with phoneticization.

It is generally agreed that the superiority of the alphabet to pictographic, syllabic, and ideographic scripts is generally attributed to its unique ability to represent speech. Moreover, as Liu claims,

“The linearity, simplicity and analytical writing have facilitated its [alphabetical writing] dissemination around the world.”

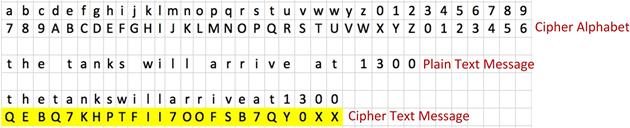

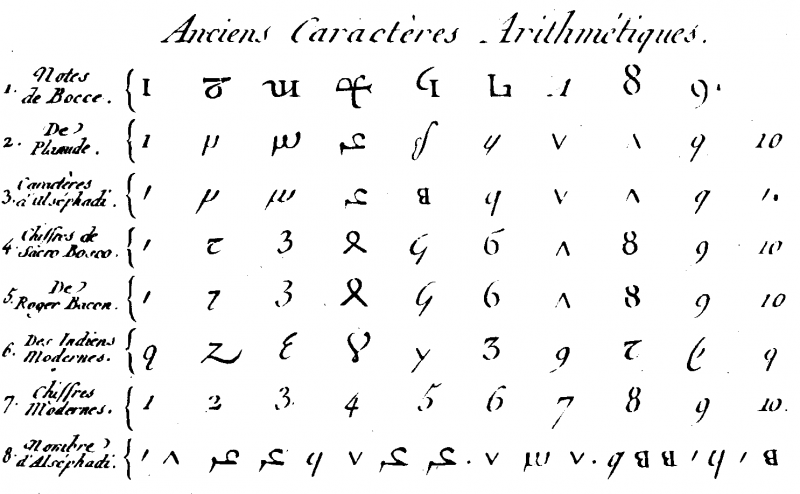

It is important, however, to keep in mind that the modern alphabetic writing systems are not purely phonographic. The ancient Greeks and Romans used letters from their own alphabets to represent numbers, hence, an alphabet that is both a phonetic tool and alphanumerical system. Quite a few of those Greek and Latin letters were the building blocks of the written representation of the ideas and concepts in algebra, geometry, trigonometry and physics.

Indeed, the numerical function of the alphabet has been there since antiquity. Only in the second half of 20th century has the treatment of the English alphabet – a derivative of Latin (and Greek before that) – as a total ideographic (algorithmic) system been greatly developed and implemented in biotechnology and cryptography.

However, the alphanumeric system of Greek and Roman script would not have developed into modern science and technology without a pictographic writing system that may just have been what humans first wrote in the ancient states in Mesopotamia, China and Egypt. In that sense, Liu seems to ignore the inclusion of numbers as examples of a pictographic writing system that has had far reaching implications for our modern world. Their origin, however, is a key ingredient in the history of writing.

Virtually every writing system started early on with the representation of numbers and quantities in a variety of ways. Which means, as Liu is eager to point out, that, rather than evolving from pictograph to syllabic writing and then to phoneticization,

“writing systems could have emerged from a much more complex set of semiotic situations than the single need to record human speech. The use of weights, measures, and currency presuppose accurate numerical notation and record keeping, which appear to have played a seminal role in the development of ancient writing.”

So numbers, as inherited from the Arabs who, in turn, took them from India, are in fact the descendants of much earlier pictographs (representations of material objects in the real world) which eventually evolved into the ideographs (representations of ideas) that they have been since Middle Ages.

Which brings us back to the technology and computers that govern our daily lives. A modern world that is built on a mixture of phonographic, pictographic, and above all, ideographic writing systems that help us explore the universe, the human mind, and our connection to each other. It all started, of course, with that mixture describing the vastly complex concepts in mathematics.

“Mathematics directs the flow of the universe, lurks behind its shapes and curves and holds the reins of everything from tiny atoms, to the biggest stars.” ~ Edward Frenkel

So even though writing may have originated as simply playing with marks or idly scribbling – at least somewhere in pre-historic Surrey – it can develop into a medium for the conquest of time and space, making possible records of the past and establishing communication networks that allow the control of vast empires, and urging us to into space exploration. (“Time and Space”).

* * *

Time and space were in an uneasy relationship for the ancient Greeks who valued more the temporal arts (music, poetry, dance) and disparaged the spatial arts (sculpture, painting, architecture). Plato saw writing as just another visual art belonging to the lowly spatial arts and feared that it would take place of – or even destroy – memory.

That notion, in turn, connects with the uneasiness of the almost total reliance of modern people on technology and the hugely increased importance of computers as repositories of human knowledge. Once we’ve transferred our memories, our reminders for tasks, our computational skills onto a machine, have we freed our brains for more important mental work to get us through the really important aspects of our life, or are we left with a vacuum to fill with feelings and intentions to connect with others and to gather more and more visual/auditory sensations to download onto our hard drives?

* * *

That uneasy relationship between speech and writing as exemplified in Plato and the ancient Greek philosophers, is one of Derida’s most discussed topics.

According to Derrida, for Plato, Rousseau, Saussure, and Levi-Strauss, speech is much more important than writing. For them, while spoken words are the symbols of mental experience, written words are the symbols of that already existing symbol. In other words, as representations of speech, written words are already twice removed from the original thought. As a result, Derrida attempts to illustrate that the structure of writing is more important and actually even ‘older’ than the supposedly pure structure typical of speech.

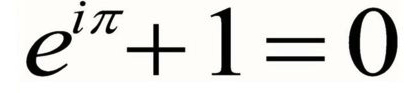

So here is a tentative illustration of the above: How about a thought that is so complex and abstract and even ambiguous, that only a written representation would help it be shaped, simplified and distilled into a universally understandable message? A message written as a mathematical or physics theorem? In that sense, is an equation the purest, most synthesized representation of a complex abstraction?

Euler’s identity:

Source

* * *

Liu claims that:

“the same phonetic function [of alphabetical writing] is also capable of suppressing the spatial, architectonic, and gestural dimensions of human communication”

I don’t think any writing system in the world can overcome those limitations, including the logographic ones used by the Chinese and Japanese. It seems to me that without the help of images or videos, writing will never be able to fully convey the whole complexity of non-verbal communication that those dimensions imply.

Kittler takes this notion even further in the context of printed text. It can be inferred that, for him, the invention of the typewriter – and its personal use in particular – deals a final blow to the person’s individuality as expressed by handwriting. And it is not limited to only alphabetical writing, it seems. I believe that the very act of replacing the pen with the keyboard renders the person faceless. In “Gramophone, Film, Typewriter” Kittler claims that

“In standardized texts, paper and body, writing and soul fall apart. Typewriters do not store individuals, their letters do not communicate a hereafter that perfectly alphabetized readers could subsequently hallucinate as meaning.”

Hence, the embodiment of writing is lost in that process (“Body”). The unique movements of the hand with the pen dissolve into the mechanical stroke of the key which in turn produces the sterile, uniform, anonymous shapes of the letterset. What is left is the pure content of the text without the sensual, organic feel of the handwritten letters that conveys emotions and non-verbality at an almost unconscious level.

How then can we imbue the typescript on our monitors or sheets of paper with the subtleties of our own personality? Well, we can use different typefaces (fonts) to express an overall mood or intention. But they are not organic either. They have been pre-drawn, pre-shaped, pre-sculptured by a typography designer somewhere and sometime before the moment of typing. In a sense, they are the equivalent of the mass produced garments we buy in the store that send a certain message when we put them on.

* * *

Interestingly, at some point we discovered that the same alphabetical writing, with all its limitations as to the non-written human communication, could produce rudimentary visualizations of our emotions or intentions in the domain of digital text – the character-based emoticons.

So, going back to the underlining notion in Lydia Liu’s essay of juxtaposing the different writing systems, as a combination of letters, punctuation symbols and numbers, an emoticon is, in essence, a mixture of writing systems, alphabetical and logographic – just like the writing in mathematics.

It is important to mention that there are Japanese, Chinese and Korean versions of emoticons, and perhaps a few other exotic ones. Interestingly, most of them are based on the same punctuation symbols and a just few letters and numbers introduced by the alphabetic writing of the Western world. In general, they are capable of relaying the intended emotion and overall meaning across the different cultures of Internet users and even beyond the digital. As such, they are a telling example of the global dominance of alphabetical writing, spurred by the Internet, as revealed on the computer and smartphone keyboards.

In conclusion, let me attempt to answer Lydia Liu’s final question in her essay on writing (“In what ways does digital media transform the idea of alphabetical writing to take us where we are or into ‘a global village’?”).

It seems to me that, with respect to digital technologies and the Internet, the “global village”, as termed by Marshall McLuhan, is a noisy chat room where a multitude of patchworks of writing systems shape up an unprecedented mutual comprehension. All that courtesy of the inherent flexibility of the alphabetical writing system to provide the alphanumerical foundations for mathematics, cryptology, and the language of computing.

As participants in this, however, it looks to me as though we are left wanting for a simpler and unambiguous representations of our feelings through writing. So are we yearning to go back to the simplicity of the pictograph in order to connect and be connected? In doing that, we seem to revert to the more economical and simplified array of symbols that are uncannily harking back to a much earlier stage in our history.

An age when Taffy would have been proud with her misconstrued drawings, after all. 🙂

\(^ ^)/

Bibliography:

Derrida, J. (1976). Of Grammatology, trans. G. Spivak. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University.

Kipling, R. How the Alphabet Was Made. [Online].

http://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/79/just-so-stories/1303/how-the-alphabet-was-made/

Kipling, R. How the First Letter Was Written. [Online].

http://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/79/just-so-stories/1302/how-the-first-letter-was-written/

Kittler, F. (1999). Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Translated with an Introduction by Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Lepaludier, L. (2003). Kipling and Semiotics in “How the Alphabet Was Made”. Journal of the Short Story in English [Online], 41 | Autumn 2003. URL: http://jsse.revues.org/309

Liu, L. (2010). Writing. In W. Mitchell and M. Hansen (Eds.), Critical Terms for Media Studies (pp.310-326). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Mitchell, W. and Hansen, M. (2010). Time and Space. In W. Mitchell and M. Hansen (Eds.), Critical Terms for Media Studies (pp.101-113). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Stiegler, B. (2010). Memory. In W. Mitchell and M. Hansen (Eds.), Critical Terms for Media Studies (pp.64-87). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Wegenstein, B. (2010). Body. In W. Mitchell and M. Hansen (Eds.), Critical Terms for Media Studies (pp.19-34). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Add yours Comments – 1

I came across this interesting scientific study on how Amazonian people communicate concepts such as time: http://www.linguisticsociety.org/sites/default/files/Lg_03_16.pdf

The article is similar in ways to the story of the birth of the English alphabet. Particularly in how time and language meld together and are interpreted both through auditory and visual components such as the use of hand gestures to the sky to tell the time of day..