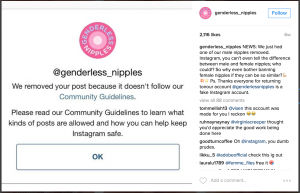

This project popped up in my timeline this week, and it made me think of some of our thoughts of last week on how algorithms are a mirror of society. The account is challenging instagram’s policy on nudity and more specifically, male versus female nipples. The algorithm is not able to distinguish them – but to us culturally, they are (or were). I liked how the role of the algorithm in this instance is used to support the critique, challenging instagram to reconsider their policy.

This project popped up in my timeline this week, and it made me think of some of our thoughts of last week on how algorithms are a mirror of society. The account is challenging instagram’s policy on nudity and more specifically, male versus female nipples. The algorithm is not able to distinguish them – but to us culturally, they are (or were). I liked how the role of the algorithm in this instance is used to support the critique, challenging instagram to reconsider their policy.

This resonates with Donna Haraway’s ideas on a post-gender society. In her Cyborg Manifesto, she positions the cyborg as a construction to uncover the ambiguity in boundaries between “natural and artificial, mind and body, self-developing and externally designed, and many other distinctions that used to apply to organisms and machines.”

An interesting exploration following out of this is digital persona Huge Harry, who explores human facial expression as an efficient means to signal internal states to another human being. For a better understanding between digital computers and human persons, it proposes that humans should lend their magnificent facial hardware to digital computers. In this video you can see how Huge Harry is presenting his work, Arthur Elsenaars face, very similar to how we might be introduced to new computational artefacts (e.g. an Apple Keynote).

Watching this, I can’t help but feel bad for Arthur, and in return, I start to wonder if we are being ethical in the way we handle or deal with objects. This anthropomorphising, projecting human emotions onto things, can also be found in responses to Rafaello D’Andrea’s Robotic Chair, which destructs and reassembles itself.

But I feel like we might miss the point in feeling bad for objects – in order to do so, we need a far better understanding of what it is like to be an object. In his book Alien Phenomenology, Ian Bogost argues for this type of understanding. For example, he mentions, if we talk about ethics, its always ethics for us (humans). But our world is made up of much more, and by taking this anthropocentric perspective we are missing out and neglecting other elements. However, he also mentions that there is a limit to our understanding: we can never fully comprehend what it is like to be a thing – and I think this relates back to our readings on the body. We perceive the world through our body, and this gives us a unique perspective. Things perceive the world through their thingness, and, as we can never be fully thing, we will never fully understand this (just as things, non-humans, will never fully understand humans).

Following these thoughts, I am getting more and more curious on the “senses” of the algorithm: how does an algorithm perceive, and what logic does it use to make sense of its input? But I would like to explore this in ways that are not creating as much of a we/they distinction between us, the humans and them, the machines. Similar as how Donna Haraway positions her argument to be “for pleasure in the confusions of boundaries and for responsibility in their construction.”

Leave me a Comment