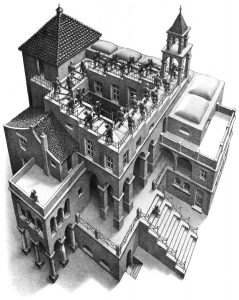

Hofstadter in his famous book “Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid” written in 1979, brings art, science, and philosophy together to explore the idea of “strange loops”. A strange loop could be seen in a concept being recursively defined, evaluated or extended by itself. Just like how Gödel used Number theory itself to assess the validity of mathematical statements in number theory, how Escher drew the impossible staircase and how Bach’s “Canon per Tonos” in his “Musical Offering” magically concludes where it begins; meaning you can smoothly replay it from the beginning, despite the fact that the modulation rises throughout the canon. Hofstadter also finds this phenomenon in the notion of objectivity in science.

I will first explain Carroll’s paradox, then discuss how the strange loop of evidence appears based on this paradox. After that, I will explain Oakeshott’s idea about scientific methods and how Winch adopted his idea to address Carroll’s paradox in science.

What the Tortoise Said to Achilles

Achilles and the Tortoise is a series of dialogues in the form of an allegory which explores a few interesting paradoxes known as Zeno’s paradoxes. Lewis Carroll – the author of Alice in Wonderland – adopted Zeno’s allegory and playfully made his own dialogue, What the Tortoise Said to Achilles (known as Carroll’s paradox). You can read the dialogue either in Hofstadter’s book or on this page:

http://platonicrealms.com/encyclopedia/Carrolls-Paradox

Strange Loop of Evidence

Hofstadter explains how the objectivity of orthodox science is challenged by fringe scientists, who claim that the standard procedures in science must be brought into question. For instance, those who believe in ESP (sixth sense) condemn common scientific methods for their inability to help scientists to study this phenomenon. They believe ESP exists, but as soon as scientists try to scrutinize it in the lab, it mysteriously vanishes and therefore, it is scientifically claimed to be non-existent. What do ESP believers say? Scientific methods are wrong and must be changed.

There rises the need to evaluate the methods of interpretation and bring evidence to justify them. Based on Carroll’s paradox, this process of bringing evidence could go on forever (Hofstadter, 1979). How? Scientists need to bring evidence that a particular method ensures the objectivity of science. But how do you prove that the evidence itself can be justified? By a new evidence? What if a peer scientist asks you to prove that your evidence for the evidence for the objectivity of the method is justifiable? Would you seek a new evidence? See the problem?

Michael Oakeshott could introduce a new perspective into this loop.

Faith or Intelligence?

In this part, please take note “rational”‘s meaning in this context depends on whether its “r” is lowercase or uppercase.

In “Rationalism and Politics”, Oakeshott first explains the fallacy of Rationalists – those who practice the process of deductive reasoning based on universal principles in order to gain on new theories which could help them in decision making – in politics and social activities and further on, extends the same concept in scientific methods. Although the book is written in 1962, his ideas seem to be a good hint for Hofstadter’s question.

Oakeshott argues that “The fallacy of Rationalism, in other words, is that the knowledge it identifies as rational is itself the product of experience and judgment. It consists of rules, methods, or techniques abstracted from practice, tools that, far from being substitutes for experience and judgment, cannot be effectively used in the absence of experience and judgment.” (Nardin, 2016)

He believes that rationality of conduct is not something which happens before the conduct, rather it is a character of the conduct itself. Therefore, rationality is not merely “intelligence”, but “faithfulness” to the knowledge we have of doing the activity; a knowledge which could be very limited at the beginning, but we expand it by practicing it and adding more to the knowledge as we gain more experience in the practice. A rational conduct does not seek to achieve its purpose, rather it seeks success. A scientist might define a purpose and a problem advance to the conduct of the research. However, the way they approach the activity of scientific inquiry is not independently premeditated, rather it is simply derived from their prior experiences and judgments (Oakeshott, 1977).

It is very interesting how the notion of “faith” has been used to object Rationalism, however, in Daston and Galison’s “Objectivity”, faith is attributed to the completely mechanical/Rationalist procedure of photography.

Rationality* Is not Formulating

*Rationality in the title is with lower case R. Rationalists believe in formulating. But rational conduct is not, or shall I say “should not be”.

Peter Winch in his “The Idea of Social Science and Its Relation to Philosophy”, refers to Oakeshott’s ideas and claims that since human activity is not as Rationalists describe it (premeditation before conduct), it cannot be formulated. But what would happen if we could formulate it? In that case, we had to consider a set of rules that should be applied to the practice, then we had to define another higher level set of rules to determine how the first set should be applied, and then we needed the third level set for the second level set and so on (Winch, 2003). Basically, Winch suggests that if we consider human activities (including scientific studies) Rationalist procedures, then we would find ourselves in Hofstadter’s strange loop.

In this case, to me, even the scientific methods seem socially constructed and subjective and it’s starting to get very confusing. What do you think? Do you think Rationalism is more realistic or Oakeshott’s idea? Or none of them? After answering this question, we might be able to address how to deal with evidence in objectivity, however, the question of Rationalism vs Oakeshott might not even yield an answer.

It would be a good idea to take a look at Asura’s post “Let’s not talk about objectivity”. The paper Asura has posted addresses the same never-ending loop as one of the reasons we should not kick the problem up the stairs in search of evidence for evidence.

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

References:

Hofstadter, D. R. (1979). Gödel, Escher, Bach: an eternal golden braid. New York: Basic Books.

Oakeshott, M. J. (1977). Rationalism in politics and other essays (Reprint). London: Methuen u.a.

Winch, P. (2003). The idea of a social science and its relation to philosophy. London: Routledge.

Nardin, T. (2016). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/oakeshott/>.

Leave me a Comment