————-

storm of images

Describing the “dematerialization of material culture,” the archaeologist Colin Renfrew laments the current separation “between communication and substance,” the image having become increasingly “electronic and thus no longer tangible”

Indeed, no matter how many digital images you take of the thorn in your thumb, it remains there, and should you print those images, the medium turns out to have amplified (not annihilated) “palpable material reality”

These passages about our experiences of images sparked a few thoughts as I was reading them. The storm of images brought to mind the image Doenja posted of Erik Kessel’s 24 hrs, an excellent visualization of what our daily image consumption feels like if the electronic were made tangible.

And as for the physical, material experience of the image, do we need to print out images? Is that the only way they can exist materially? How much time did we spend handling images back when images were material in the sense they seemed to be discussed here? I certainly remember getting a roll of film back after being developed and flipping through them, perhaps one might make it to a frame or photo album. But in some way it seems I may spend more time “touching” images now by scrolling through Instagram on my phone.

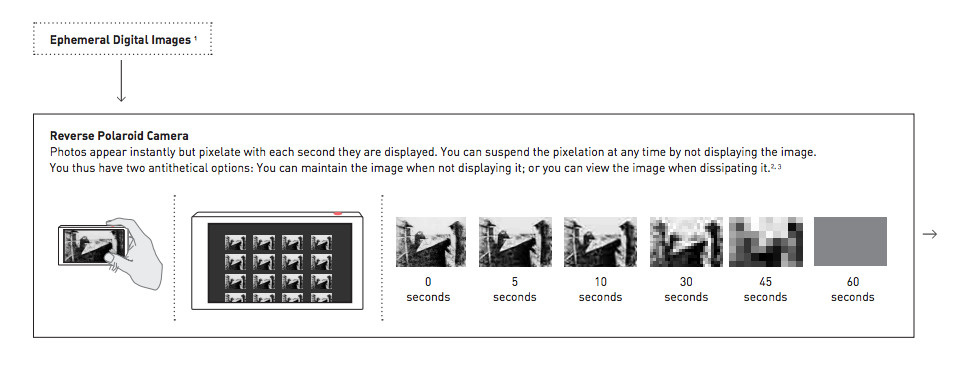

This also reminded me of the work of Pierce and Paulos, “Some Variations on a Counter Functional Digital Camera” and “Counterfunctional Things: Exploring Possibilities in Designing Digital Limitations.” In their pictorial and paper presented at DIS2014, the two offered (counter)perspectives on digital photography, from a camera that could only take one image at a time to another that pixelate every second they were displayed. Are these (counter)perspectives and apps like Snapchat moving towards a sort of post-permanence or post-materiality?

————-

Some scholars have argued that the arrival of computer-processed images has produced a radical transformation in the ontology of the image, altering its fundamental essence as an object of human experience

what is important and real are the ones and zeros of the binary code

Getting down to the basics of what the images are and the nature of their being, does the digital really make a difference? Does the face that images are created by code change the idea of an image substantially as opposed to when the process involved chemical reactions? It seems like the digital here, the ones and zeros, is still so far from the average person’s understanding (much like the average person’s understanding of algorithms). They may have knowledge of it, as they had knowledge of chemical processes involved in analog images. But even as someone who has experience mixing chemicals, developing film, and printing in the darkroom, in some ways I may have a better understanding of the ones and zeros of my digital images than I do in the chemistry of my analog images.

————-

The invention of new means of image production and reproduction… is often accompanied by a widespread perception that a “pictorial turn “ is taking place, often with the prediction of disastrous consequences for culture

I have been thinking about this quite a bit recently, the latest perception of a pictorial turn that may be occurring with 360-degree video particularly in relation to the news media. In December I joined a New York Times photographer on a 360 video shoot and interviewed him about his concerns for reporting in 360.

I wasn’t really sure what to expect, but I was maybe a bit surprised when he focused on his experience as the image-maker. He was particularly concerned with the intimacy that he normally establishes with a subject and the new influence that may occur with 360 production. The connection between a photojournalist and the subject that develops over the course of working closely together enables the opportunity to take impactful images – and the production of VR stories may negatively impact that intimacy if the reporter is expected to be absent from the final video. There was also the concern about the level of influence VR shoots may have on the subject. Rather than the photojournalist just following a subject’s normal activities with a camera, equipment must be set up in advance and subjects might be encouraged or influenced to modify their behavior so the 360-camera will capture them.

Thinking back on other discussions of new media images that I’ve read, the changes in the actual experience of creating an image seems often absent (though admittedly, perhaps I need to read more), but have certainly changed with new technology as well.

————-

Add yours Comments – 1

Great post, Reese. Your question asking about the implications of the proliferation of digital images (does the digital make a difference?) made me immediately think of one of Trevor Paglen’s provocations in his article (https://thenewinquiry.com/essays/invisible-images-your-pictures-are-looking-at-you/), listed as an additional reading for this week. This gives us one way answering your question…

He says: “What’s truly revolutionary about the advent of digital images is the fact that they are fundamentally machine-readable: they can only be seen by humans in special circumstances and for short periods of time. A photograph shot on a phone creates a machine-readable file that does not reflect light in such a way as to be perceptible to a human eye. A secondary application, like a software-based photo viewer paired with a liquid crystal display and backlight may create something that a human can look at, but the image only appears to human eyes temporarily before reverting back to its immaterial machine form when the phone is put away or the display is turned off. However, the image doesn’t need to be turned into human-readable form in order for a machine to do something with it. This is fundamentally different than a roll of undeveloped film. Although film, too, must be coaxed by a chemical process into a form visible by human eyes, the undeveloped film negative isn’t readable by a human or machine.

The fact that digital images are fundamentally machine-readable regardless of a human subject has enormous implications. It allows for the automation of vision on an enormous scale and, along with it, the exercise of power on dramatically larger and smaller scales than have ever been possible.”