You move slowly. Your face: pensive. Immersed in the experience of art, yet simultaneously aware of surrounding other pensive, immersed, slowly moving humans – as to not get in their way, or disturb the seemingly pre-defined rhythm that moves the whole body of museum visitors from one work to the next. I always enjoy shifting from the cacophony of sounds, the rush and the haste of public transport to this whispering waltz in the museum-world, of which (almost) everyone seems to know the rules. But not this time.

Erdem Taşdelen’s Quantified Self Poems are displayed in the windows of the Contemporary Art Gallery. As I am taking in the poems at the crossing of Nelson and Richard street in downtown Vancouver, I am in the midst of everyday life on the streets. Cars rushing by, the sound of a core drill penetrating the concrete, even a spat between two homeless men – they are all part of the experience.

Erdem Taşdelen’s work explores how we learn to operate channels that allow self-expression. He describes the Quantified Self Poems as “an experiment to see if it is possible to set up parameters for self-expression, without prescribing the content of the outcome.”

The Quantified Self was a term introduced a decade ago. It promotes incorporating technology in everyday life to gather data on the way we live, with the hope of self-improvement. This includes products such as activity trackers, sleep monitors and, apparently, emotion sensing apps. With his poems, Taşdelen takes these notions a step further, to quantified self expression.

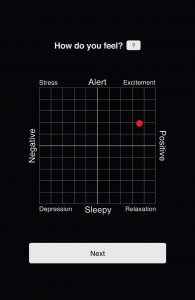

The first step of Taşdelen’s experiment involved him interacting with the app Emotion Sense, three times a day, for three months. The Emotion Sense app, created by a team from the University of Cambridge, was part of a ‘Global happiness-tracking’ research project and was made to measure emotions. Through self-report surveys (notification driven or self-initiated) users can select a point on the affect grid, and rate their positive and negative affect on a sliding scale. Based on this input, a numeric value reflecting the emotion is assigned to every interaction with the app.

Taşdelen’s approximately 270 quantified emotions are the first data set for the Quantified

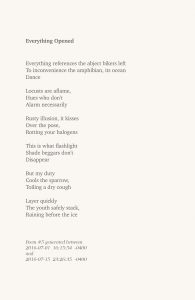

Self Poems. The second data set was provided by Daniel Zomparelli, a Vancouver based poet. He compiled dictionary of 2000 words and subjectively assigned numeric values to each word. With these two data sources, Ali Bilgin Arslan wrote a program that used the data from the Emotion Sense to draw words from the dictionary to fill poem structures with the closest numeric values. In the poems, each word corresponds with one of Tasdelen’s interaction with the app. The twelve silk screen prints of the Quantified Self Poems as displayed at the CAG all include the ontology of the algorithm at work, stating between which dates the poem was generated. The poems are accompanied with screen captures from the emotion sense app.

The poems are made up of strange strings of words such as “27 ivory cowboys” and sentences like “their masked farmhouse in Spring, bugged the ass” or phrases that start as a cheeky poem, but end with sheer absurdity: “a playground coexists for French kissing, relaxing a crimson octopus.”

When reading the poems as a whole, these were the kinds of incongruities that disrupted my experience and shifted me out of my museum-waltz that I already had a hard time getting into. However, some sentences genuinely moved me, containing qualities that I expect of poems: “while eternal kids laugh”, “who doesn’t mourn when older than morning”, “rusty illusion, it kisses, over the pose, rotting your halogens.”

When I started trying to trace back which mood each word might represent, the poems extrapolate the inability of this app to truly know emotions – even more so than if it were a static monthly report on your moods. As I am trying to make sense of one word following another, I can’t relate. The algorithm can’t see everything in relation, or read between the lines, the way poetry so beautifully does. And while the intention of the artist was not to create a descriptive poetry machine, it is interesting to see how the input – at the very start, Taşdelen’s lived emotions – can become so morphed and even lost through quantification, code and logic. To come back at Taşdelen’s statement of his inquiry – to see if it is possible to set up parameters for self-expression, without prescribing the content of the outcome – I wonder: whose self exactly, is being expressed? I reached out to Erdem Taşdelen and asked him if he recognised himself in the poems:

“I notice things in the poems based on the time period they were generated and see how they relate to what was going on in my life at that time. But this is only discernible to me.”

When asking him if he ever felt misunderstood by the generated poems, he said:

“There is no way to be understood by the poems, because there is not a correct way to understand any of it. The experiment wasn’t done wit the purpose of creating the best expression of emotion.”

It was fascinating to me how Taşdelen did not see these poems as his personal emotional records at all. To him, this was not of importance: his data was just a part of the work. The words of Daniel Zomarelli, the code of Ali Bilgin Arslan, the app by the researchers from Cambridge – they are now all, knowingly or unknowingly, poets in part. Erdem Taşdelen was just part of that poetry making ensemble, and his seemingly distant relation on the poems seems to reflect just that. To me, this resonates with the ideas Donna Haraway presents in her Cyborg Manifesto: no thing exists as an absolute – we exist relationally. The way Erdem Taşdelen presents himself as part of the ensemble is not so different to the way in which I described myself as part of the whole body of museum visitors. And similar as Taşdelen may see himself part of the algorithm, the algorithmic poems effortlessly blend into the streets of Vancouver, too.

The poems question ideas on authorship. For me, this relates to our readings and discussions on accountability. If the authors become opaque, who can we turn to? If algorithms produce undesirable, unethical results, who is responsible? A crimson octopus? 27 Ivory cowboys?

Leave me a Comment