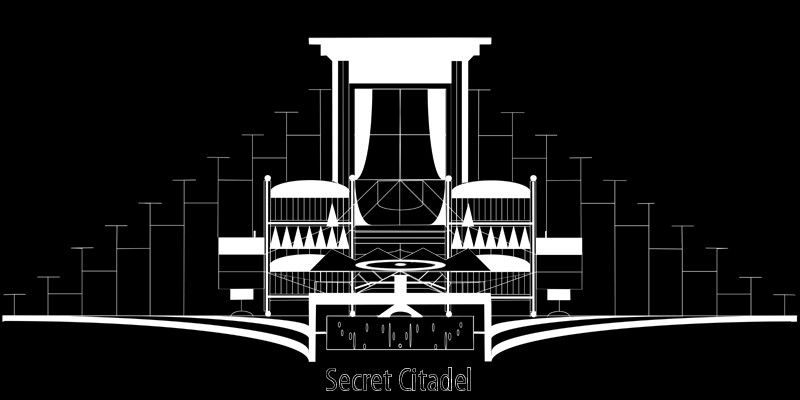

Figure 1. Secret Citadel, 2013. Mixed Media Sculpture/Video installation. Surrey Art Gallery.

Abstract

Secret Citadel is a multimedia installation created by artist Graeme Patterson, 2013. The work presents a boyhood scrapbook of sorts that combines images and memories from his past with revisions from our present time. The media forms included are: stop-motion animation, film, projection, sound, costumes, and large scale sculptures. This paper discusses Secret Citadel and the relationship between the work and memory repositories. How is our memory mediated? What is cultural memory? I will reflect on how the audience ultimately becomes an author in the remaining story, whereby the installation space and the threshold space of memory meld together to poignantly provide a space for the artist and the audience to live these memories together, again and again.

Figure 2-3. Secret Citadel, 2013. Mixed Media Sculpture/Video installation. Surrey Art Gallery.

Introduction

Secret Citadel is a multimedia installation created by Sackville artist Graeme Patterson, 2013. The four-part chronologically ordered installation is made up of The Mountain, Camp Wakonda, Grudge Match and Player Piano Waltz. Patterson creates a captivating worlds-within-worlds, visual array of media that consists of stop-motion animations, video projections, ambient sound scores, large-scale sculptures, text and costumes. Together the combined pieces draw the audience into a vivid world filled with nostalgic images of Patterson’s trials and tribulations as a child growing up in suburban Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (see Fig. 1-3). The work explores the universal themes of male friendship, longing, and loss.

Upon entering the exhibition space, the viewer can engage with the large-scale models, explore the area, and watch numerous stop-motion animations coupled with the ambient sound compositions. The miniature imagery entices viewers to immerse themselves in the experience, perhaps invoking a dreamlike encounter between interior vibrations and exterior reverberations.

Figure 4-5. Camp Wakonda, Secret Citadel, 2013. Mixed Media Sculpture/Video installation. Surrey Art Gallery.

Aesthetically, Secret Citadel is a visual scrapbook of sorts that prompts audiences to navigate through fantastical representations of Patterson’s childhood. The centerpiece of Secret Citadel is The Mountain, where Patterson reimagines his own home and his best friend Yuki’s house in suburban Saskatoon (see Fig. 4). Miniature projections loop inside each house, depicting the process of building the installation. The stop-animation films also introduce imagery of a cougar and bison mascot. The two houses connect via tunnels under the large mountain made up of fun fur, trees, wooden poles, metal power lines and blankets. Inside the mountain is a recreation of Patterson’s artist studio, consisting of materials such as popsicle sticks, bottle caps, cardboard, screws, sandpaper, wood scraps and other readily found domestic objects (see Fig. 5). The piece is playful and conjures up imaginary of worlds-within-worlds.

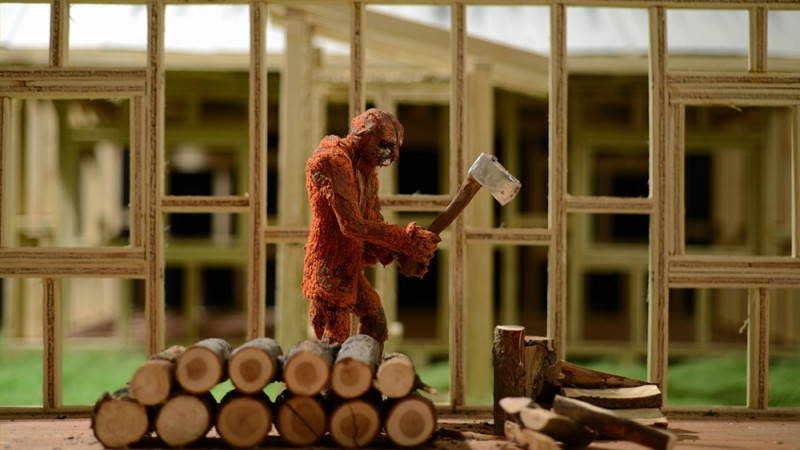

Figure 6-7. Camp Wakonda, Secret Citadel, 2013. Mixed Media Sculpture/Video installation. Surrey Art Gallery.

Camp Wakonda builds upon the first model, depicting a car crash and a friend being shot in the back during an archery game. The piece also reveals adolescent narratives such as the cougar and bison mascots playing games, burning plastic figurines, cutting wood, and running though forests chasing animals (see Fig. 6-7). The installation is large-scale, somewhat symmetrical, made up of two double row bunk beds, models of summer camp buildings, lights, miniature projections, ladders, trees, grass, a bridge, car crash, and a cougar and bison. The bridge joins both bunk beds; possibly to link the artists present memory to the past, between play and tragedy.

Figure 8-9. Grudge Match, Secret Citadel, 2013. Mixed Media Sculpture/Video installation. Surrey Art Gallery.

Grudge Match is the third installment in the exhibition. The piece depicts a high school wrestling match between two equally matched players. The large-scale sculpture consists of two gymnasium bleachers with scratches and signatures scribed onto the wooden planks (see Fig. 8-9). A miniature gymnasium is built beneath the bleachers. Inside images of the two mascots, blue wresting matts, basketball nets, benches, and lights fill the gym. Adjacent are the coach’s offices, locker rooms, change rooms, bathrooms, and weight room. Patterson’s gymnasium is a place of completion, tension, and failure. His mascots are presented at a pivotal moment in their adolescence, with equal weight being suspended between friendship and winning. The scene presents the audience with the possibility of dreaming.

Figure 10. Player Piano Waltz, Secret Citadel, 2013. Mixed Media Sculpture/Video installation. Surrey Art Gallery.

The final piece Player Piano Waltz, is dark, sorrowful and powerful. The piece portrays the two mascots much older in age, inhabiting similar spaces and activities, yet never physically connecting. The work layers upon the previous parts, highlights the stop-motion animations, large and small-scale projections on the gallery walls/ monitors inside the miniature set.[1] Additionally, an upright piano plays a melancholic waltz track when the viewer drops a coin in the dispenser (see Fig. 10). Patterson continues to showcase the two animal mascots, to serve as symbols of a transition from childhood to adulthood; “the transition to loneness that marks the condition of maturity and that replaces the collectivity of childhood” (Patterson, 2014, pg. 164).

Functionally, the installation is a historical archive, revisiting treasures and cultural memories of childhood. However, combined the installation is not the artist’s life story, “despite tantalizing hints that lead us to believe it is as such” (Patterson, 2014, pg. 164). I suggest that Patterson’s work offers audiences a layered revision of memory collection practices that challenge us to consider how we may remember the past through memorabilia, images, sound, media and objects. A few questions arise: How is our memory mediated? What is cultural memory? What new forms can be explored through this style of storytelling?

Memory, Dreams and Temporal Shifts

The word memory comes from the Middle English memorie, which derived from the Anglo-French memoire, or the Latin memoria and memor, meaning remembering or mindful (Mastin, 2010). Memory is the ability to remember previously experienced impressions, recollections and feelings. We have the ability to encode, store, retrieve, learn and adapt in real-time from our memories (Mitchell and Hansen, 2010, pg. 78-79). Retrieval is sometimes difficult as memories are often elusive. Yet, physical actions can evoke sensory memories that live in the body. Thus, memory is the sum of what we remember. Secret Citadel reflects on Graeme Patterson’s memories, transforming objects to create new media versions. Patterson’s memories draw from images such as wood paneling, tunnels, summer camps, shag carpets, gymnasiums, bunk beds, and musty basement rec rooms (Patterson, 2014, pg. 19). His memories are associated [2] with objects and become fantastical reconstructions of his past.

French philosopher Jacques Derrida in his Plato’s Pharmacy, suggests that humans exteriorize memory, often resulting in a loss of knowledge, and feelings of powerlessness (Mitchell and Hansen, 2010, pg. 69). He also describes memory as collection of thoughts that hold no separation between present and past (Derrida, 1988, pg. 50-58). Building on Derrida’s notions, Bernard Stiegler in his Technics and Time, 3: Cinematic Time and the Question of Malaise, suggests that objects can be exteriorizations of consciousness (Stiegler, 2010, pg. 3-15). He argues that the amount of times we use “tools, artifacts, language” or objects can help us process, remember and experience a memory from another time (Mitchell and Hansen, 2010, pg. 65). Authors Michael Mitchell and Mark Hansen in their Critical Terms for Media Studies, further describes memory (retentional finitude), as an essential human component because we require artificial memory aids to help us remember events and details (Mitchell and Hansen, 2010, 64-65).

Complimenting Derrida, Steigler and Hansen’s arguments on the temporal nature of memory, Myrian Sepúlveda Santos in her Memory and Narrative in Social Theory, suggests that memory is performative:

“Contemporary concepts of memory are much more complex than Halbwachs could have anticipated. They construe memory as a kind of performance in which the act of remembering does not reflect either the individual’s will or social determinations, but rather the intertwining of these two forces.” (Myrian Sepúlveda Santos, 2001, pg. 165-166).

Here Santos outlines how our memories are made up of performative acts of remembrance, forgetting and belonging. Thus we can experience memory at any time, in any social and personal space. Similarly, physicist Alan Lightman in his Einstein’s Dreams, portrays many different aspects of time. He refers to time as being sticky, and people becoming stuck in routines or in moments in their lives. Both authors allude to a sort of repetitive experience that pushes the viewer to try and access a past memory through action. Secret Citadel challenges viewer’s to delve into Patterson’s perceptual lens on memory, reality, and what a times, feels like fantasy. The origin is lost, but found again, translated and to become something else altogether. Perhaps through the process of creating and reimagining his memories, moments of unstuck time are awakened, offering the viewer a chance to interact with objects which become stand-ins for moments long past; media encased in loss and yearning.

With that in mind, Mitchell and Hansen argue that the integration of memories, senses, and technologies into everyday practices has had its greatest impact in the design of artworks (Mitchell and Hansen, 2010, p.65-66). Childhood is also a continual theme in art, explored throughout history by artists who almost “unanimously tap this facet of existence as foundation of their creativity” (Patterson, 2014, pg. 60). Perhaps, Patterson’s memories are like dreams, defying time and space. Indeed, the dream as an artistic tool has also informed many artists including Hieronymous Bosch, Henry Fuseli, Odilion Redon, Frida Kahlo, Salvador Dali and Man Ray to name but a few. French poet, and avid art collector André Breton in his Manifesto of Surrealism, describes the importance of dreams:

“I have always been amazed at the way an ordinary observer lends so much more credence and attaches so much more importance to waking events than to those occurring in dreams…We are] above all the plaything of [our] memory” (Breton, 1924, pg. 7-8).[3]

Wandering through Graeme Patterson’s Secret Citadel, I felt compelled to stop, crouch, listen and engage again and again. His pieces inspired me to consider how memories can be translated, being elastic-like, with the potential to generate innovative aesthetic fragments and ethereal visual landscapes.

Secret Citadel is also unique in that it focuses on memory and representations of memory repositories. Authors Jan Assmann and John Czaplicka in their Collective Memory and Cultural Identity describe cultural memory as being characterized by its distance from the everyday and how individual memory becomes collective memory overtime through the use of technologies (Assmann and Czaplicka, 1995, pg. 125-130). These notions are particularly important when thinking about how memory is collected and what images or objects hold individual or group identity. In Secret Citadel the memory repository consists of media forms such as stop-motion animations, video projections, ambient sound scores, large-scale sculptures, text and costumes.

Sound, Film, Image and Projection Design

Mitchell and Hansen suggest that we cannot discuss the mind without “comparing it to a medium of some sort, often a medium that entails the internal display, projection, or storage and retrieval of images” (Mitchell and Hansen, 2010, pg. 41). He further discusses how our mind is a medium, whereby we internalize images, perceive and digest media inherently (Mitchell and Hansen, 2010, pg. 41-42). From this perspective, theorist Janet Murray defines agency as an aesthetic pleasure characteristic of digital environments, which results from the well-formed exploitation of the procedural and participatory properties (Murray, 1998). Using her definition, Secret Citadel is not a threshold object exactly, but it makes a strong case for the audience to experience the artist’s work through agency. That is to say, the audience moves from projection to projection, from set to set, from past to present reinterpretations. Upon entering the exhibition, I experience a pleasure of agency, watching narratives unfold in dynamically miniature worlds. I also oscillate between the models and the unfolding story. Author Levi Manovich suggests that the audience can exist simultaneously in a physical and virtual space of reality (Manovich, 2001). This tension between object and animation is what helps navigate the audience around the exhibition. Thus, viewers cannot help but be pulled into the notable silences that emerge both acoustically and metaphorically.

Secret Citadel’s sound design is haunting. Throughout the installation stop-motion footage from miniature projectors overlaps, weaves, and bleeds across the gallery space, inside and outside the models, in a prismatic display of gradations, colour, sound. Each animation consists of ambient textures such as wind, arrows hitting targets, human grunting, wood chopping etc. The sound compositions emerge as looping arrays of ambient textures and natural environmental reverberations. This acoustic design choice allows audiences to be active participants via the familiar, and ultimately, to be empathetic viewers in the unfolding story; the combined medias become new. Theorists Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin in their Remediation: Understanding New Media, describe remediation as the process by which media “digest” or adopt other media technologies (Bolter and Grusin, 2000). The majority of Secret Citadel is built out of remediated material and parts such as found/ made sound, wood, metal, plastic, fabric etc. For example, Patterson purposefully chose a high level of set design transparency to include the audience in the experience. Bolter and Grusin further suggest that such efforts are often designed to attain the effect of immediacy, spontaneity and transparency (Bolter and Grusin, 2000).

Conclusion

Graeme Patterson’s Secret Citadel captivates audiences to engage in his boyhood memories. I see his experiments with this work as liberations from convention. Through the layering of multiple stop-motion projections, sound compositions, and sculptures, the space of imagination and reality become occupied in new ways; our interactions make it exist in another form. He does this by fusing narratives and universal themes of male friendship, longing, and loss into large-scale installations. The work unfolds like a breathing diary and creates a participatory response, maybe similar in ways to walking the halls of an elementary school or wrestling on blue matts in a musky gymnasium that now exists only in memory. Ultimately, the viewer becomes a voyeur of sorts, taking meaningful action such as watching projections or dropping coins into an antique auto playing piano, listening to, and gazing through old windows at two figures alone but not forgotten.

Notes

[1] Traditionally scrapbooks hold memories from anytime or place or cultural history. In Secret Citadel Patterson creates a kind of visual scrapbook, made up of many parts, that becomes a threshold space or a kind of memory tool. Perhaps his work offers audiences a chance to live his or their own memories, again and again.

[2] In the 1800’s British psychologist David Hartley suggested that dreaming alters the strength of associative memories (Aserinsky, Kleitman 273–74). Neuropsychologist Wendy A. Suzuki describes associative memory “as the ability to learn and remember the relationship between unrelated items such as the name of someone we have just met or the aroma of a particular perfume” (Suzuki, 2005, pg. 175-79).

[3] In his Manifesto of Surrealism, Andre Breton outlines the importance of dreams among other examples as inspirations for Surrealism and daily life practices.

Works Cited

Aserinsky E, Kleitman N, “Regularly Occurring Periods of Eye Motility and Con-Current Phenomena During Sleep.” Science (1953): 118: 273–74.

Assmann, Jan, and John Czaplicka. “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity.” New German Critique 65 (1995): 125-133.

Derrida, Jacques. “Mémoires pour Paul de Man.” (1988).

Bolter, J. David, and Grusin, Richard. Remediation: Understanding New Media. MIT Press. 2000.

Breton, André. “First Manifesto of Surrealism. 1924.” Kolocotroni, Goldman, and Taxidou (1969): 307-311.

Gupta, Rashmi, and Narayanan Srinivasan. “Cognitive Neuroscience of Emotional Memory.” (2009).

Hartley, David. Observations on Man, His Frame, His Duty, and His Expectations. T. Tegg and Son Publishers, 1834.

Hill, Lizzy, Graeme Patterson, Christian Roy, Sarah Fillmore, and Melissa Bennett. Graeme Patterson: Secret Citadel. 2013. Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and the Art Gallery of Hamilton Publishers, 2014. Print.

LaBar, Kevin S., and Roberto Cabeza. “Cognitive Neuroscience of Emotional Memory.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 7.1 (2006): 54-64.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. MIT Press, 2001.

Mastin, Luke. “What Is Memory? – The Human Memory.” What Is Memory? – The Human Memory. N.p., 2010. Web. 03 Feb. 2016.

Mitchell, WJ Thomas, and Mark BN Hansen, Eds. Critical Terms for Media Studies. University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Murray, Janet Horowitz. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. Simon and Schuster, 1997.

Patterson, Graeme, Secret Citadel. 2013. Multimedia Installation. Surrey Art Gallery, Surrey BC.

Santos, Myrian Sepulveda. “Memory and Narrative in Social Theory: The Contributions of Jacques Derrida and Walter Benjamin.” Time & Society 10.2-3 (2001): 163-189.

Stiegler, Bernard. Technics and Time, 3: Cinematic Time and the Question of Malaise. Stanford University Press, 2010.

Suzuki, Wendy A. “Associative Learning and the Hippocampus.” Http://www.apa.org. American Psychological Association, Feb. 2005. Web. 15 Jan. 2015.

Works Consulted

Davis, Natalie Zemon and Starn, Randolf (1989) ‘Introduction: Memory and Counter- Memory,’ Representations Vol. 26: 1–6.

Derrida, Jacques. “Dissemination: Plato’s Pharmacy.” Translation: Barbara Johnson, The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, Edition. Vincent B. Leitch, William E. Cain, Laurie A. Fink, Barbara E. Johnson, John McGowan, and Jeffery J. Williams (New York: WW Norton, 2001) (2001).

Shanken, Edward A. “Art and Electronic Media.” (2009).

Suzuki, Wendy A., and Howard Eichenbaum. “The Neurophysiology of Memory.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 911.1 (2000): 175-191.

Leave me a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.