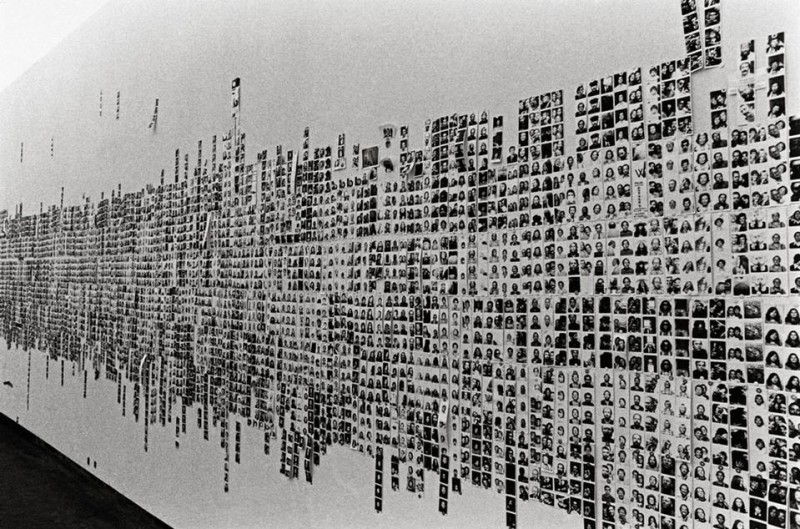

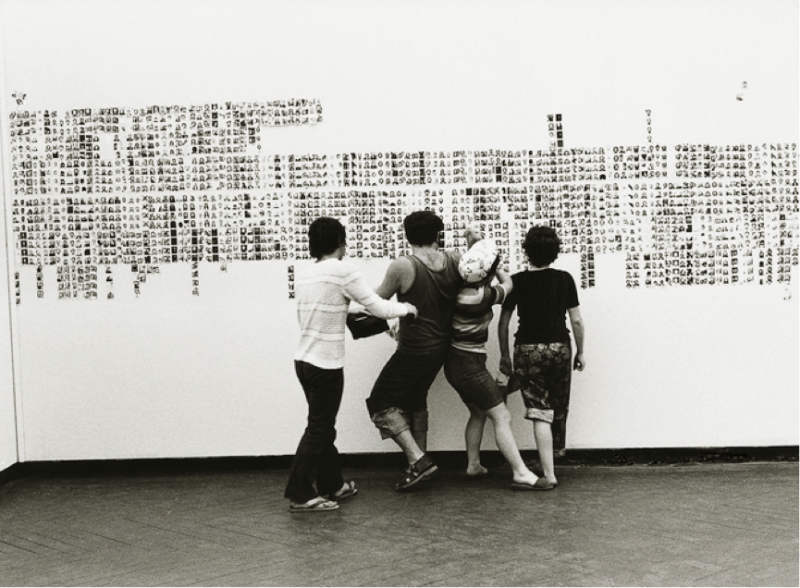

Figure 1-2. Franco Vaccari. Leave on the walls a photographic trace of your fleeting visit, 1972. Exhibition in Real Time n.4.

What kind of traces do we leave of ourselves online, in person, in face-to-face conversations? What medias help forefront or foreground these traces? Geographer Nigel Thrift in his Remembering the Technological Unconscious by Foregrounding Knowledges of Position, suggests that media is now being constituted in such a way that it structures our interactions (Thrift, 2004, pg. 175-177). His ideas reflect the concept of the technological unconscious. Thrift defines the technological unconscious as “the conceptual terrain carved out by the divergent configurations of cinema and media [which] becomes salient in relation to computational time” (CTMS, 2010, 110). Or better yet, computational processes:

“not only exceed our attention but remain fundamentally unfathomable by us. Put in another way, the forms of media-visual, aural, tactile-through which we interface with our informational universe are no longer homologous with the actual materialities, the temporal fluxes, that they mediate” (CTMS, 2010, 179-180).

I find curator Dmitry Bulatov’s definition more satisfying. He suggests that the technological unconscious:

“encompasses mythological imagination, apocalyptic visions and utopian dreams, and shows how the language and ideas of our modern post-biological society are capable of altering and reconfiguring the boundaries of our reality and our very identities” (Soft Control: Art, Science and the Technological Unconscious, 2012, Exhibition Press Release).

Bulatov describes that we are accepting of technology systems in all spheres of our lives (see Shanken, 2009, pg. 96-119):

“technological systems and their active penetration into all spheres of human life allow us to conceptualize technology as an autotelic ontological entity that plays an ever-greater role in defining human development” (Soft Control: Art, Science and the Technological Unconscious, 2012, Exhibition Press Release).

Figure 3-4. Michel de Broin, Blowback, 2013. Pile, 2010. Installation views.

On this note, Montreal artist Michel de Broin in his Blowback (2013) or Pile (2010), creates works (see fig. 3-5) that reflect on the technological unconscious. His press release outlines the technological unconscious as:

“What emerges from these transformations is a parallel universe that is strangely different than, yet in many ways uncannily similar to, our own. In this world the object is liberated from codified uses and established modes of signification, yielding unexpected exchanges, improbable detours and delightfully skewed solutions to problems whose existence was unsuspected” (de Broin, Press Release).

Figure 5. Ted Victoria. Solar Audio Window Transmission, 1969-70. Installation view.

Further to these ideas, David Beer in his Power through the Algorithm Participatory Web Cultures and the Technological Unconscious outlines the persuasive nature of technology and the “implications of software ‘sinking’ into and ‘sorting’ aspects of our everyday lives” (Beer, 2009, pg. 985).

Walter Benjamin’s in his The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction suggests the concept of optical unconscious, where what a person does not grasp is due to their perceptual limits. Benjamin argued that cinema and photography have the ability to record aspects of reality that we cannot see, hear because they are too small or quick in motion. Our retinas may receive some of this information, yet not be able to translate or perceive them (see Fig. 1-2). My point here, spurred on by Benjamin’s thoughts on perception, is that information is revealed through media forms such as cinema, and cameras that our human eye cannot see otherwise. Further, what is revealed is information from alternative movements and dimensions of reality (Flores, Web).

Artist Franco Vaccari argues that humans are more complex and perceive more than they know at any given time:

“alongside the human unconscious (defined as “plastic”) lies another type of unconscious, i.e. the technological one, which one can see at work when human beings delegate activities to tools and machines” (Campanella, 2015, pg. 259-270).

Social network platforms such as Flickr, Facebook, and Youtube push these ideas of perceptual information and reality even further. Author Darin Barney in his Terminal City? Art, Information, and the Augmenting of Vancouver, states that we cannot escape digital information or “experience[s] in which digital information, media, and networks” are processed (Barney, 2010, 126-127). These omnipresent sites become more than film or photographs, somehow tapping into our cultures obsession with archiving person experiences. As Mark Hansen describes we are part of this culture of collecting, purposefully leaving traces of ourselves on “many-to many computational networks” (CTMS, 2010, pg. 181). Vaccari stated that “the unconscious is in fact a type of social unconscious, which works autonomously and therefore symbolically to give shape to human action” (Campanella, Web). Medias give shape to actions, thoughts and unconscious desires and perspectives. Mark Hansen suggests that in “[a]ddition to storing experience, as it has always done, media today mediates the conditions of mediation” (CTMS, 2010, pg. 181). Social networks, new medias, and technologies nonetheless provide a vehicle-of-sorts for communication to/with, what philosophers Benjamin or Marshall McLuhan deem the masses (CTMS, 2010, pg. 180).

Works Cited

Barney, D. “Terminal City? Art, Information and the Augmenting of Vancouver.” The Wireless Spectrum: The Politics, Practices and Poetics of Mobile Media (2010): 115-128.

Beer, David. “Power through the Algorithm? Participatory web cultures and the technological unconscious.” New Media & Society 11.6 (2009): 985-1002.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Visual Culture: Experiences in Visual Culture (2011): 144-137.

Bulatov, Dmitry. 2012. Soft Control: Art, Science and the Technological Unconscious, Exhibition Press Release.

Campanelli, Vito. “New Aesthetic in the Perspective of Social Photography.” Postdigital Aesthetics. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2015. 259-270.

de Broin, Michel. 2011. ENTROPIC ENGINES AND RETOOLED APPLIANCES: MICHEL DE BROIN AND THE TECHNOLOGICAL UNCONSCIOUS, Exhibition Press Release. <http://micheldebroin.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/MACM-DeBroin-Sherer-Eng.pdf>.

Flores, Victor. “ImagePrintCritical Dictionary.” Côa. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Feb. 2016.

Franco, Vaccari. “Fotografia e inconscio tecnologico.” (1979).

Shanken, Edward A. “Art and Electronic Media.” (2009).

Thrift, Nigel. “Remembering the Technological Unconscious by Foregrounding Knowledges of Position.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space22.1 (2004): 175-190.

Works Consulted

Powell, Larson. The technological unconscious in German modernist literature: nature in Rilke, Benn, Brecht, and Döblin. Vol. 20. Camden House, 2008.

Visconti-Prasca, Marco. “The Condition of the Improviser (Moments and Monuments: Mission Impossible).” Contemporary Music Review 29.4 (2010): 379-386.

Add yours Comments – 2

The sad reality of the unconscious and time:

http://gtp.ruthcatlow.net

Excellent post prOphecy–the ‘technological unconscious’ is an interesting way back to our earlier conversations around materiality and visibility of computational processes and infrastructures in everyday lives. It is also a way forward to engaging with cybernetic theory, where systems and boundaries of perception, experience, and connection are blurred, whether or not it is immediately apparent to us.